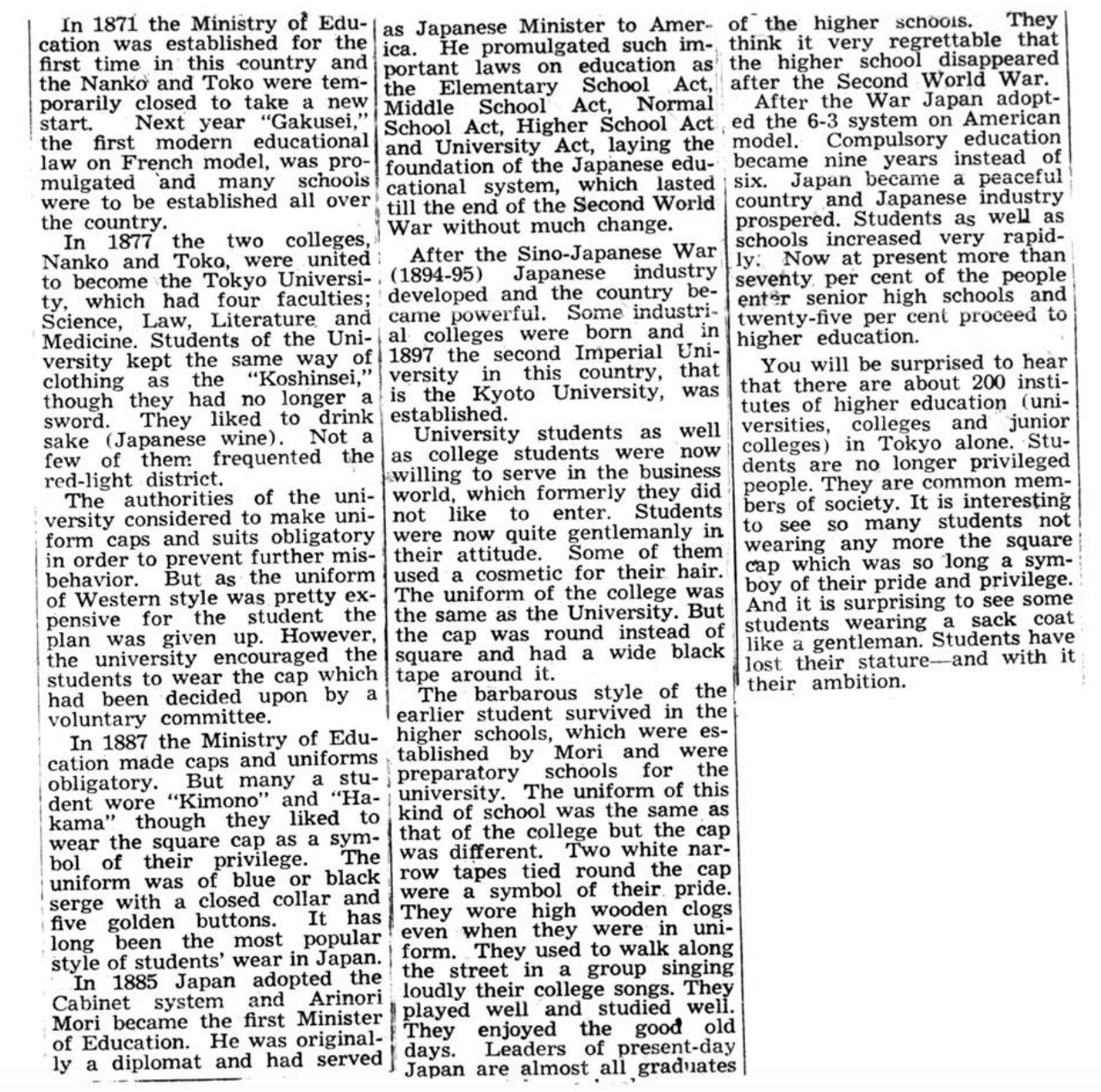

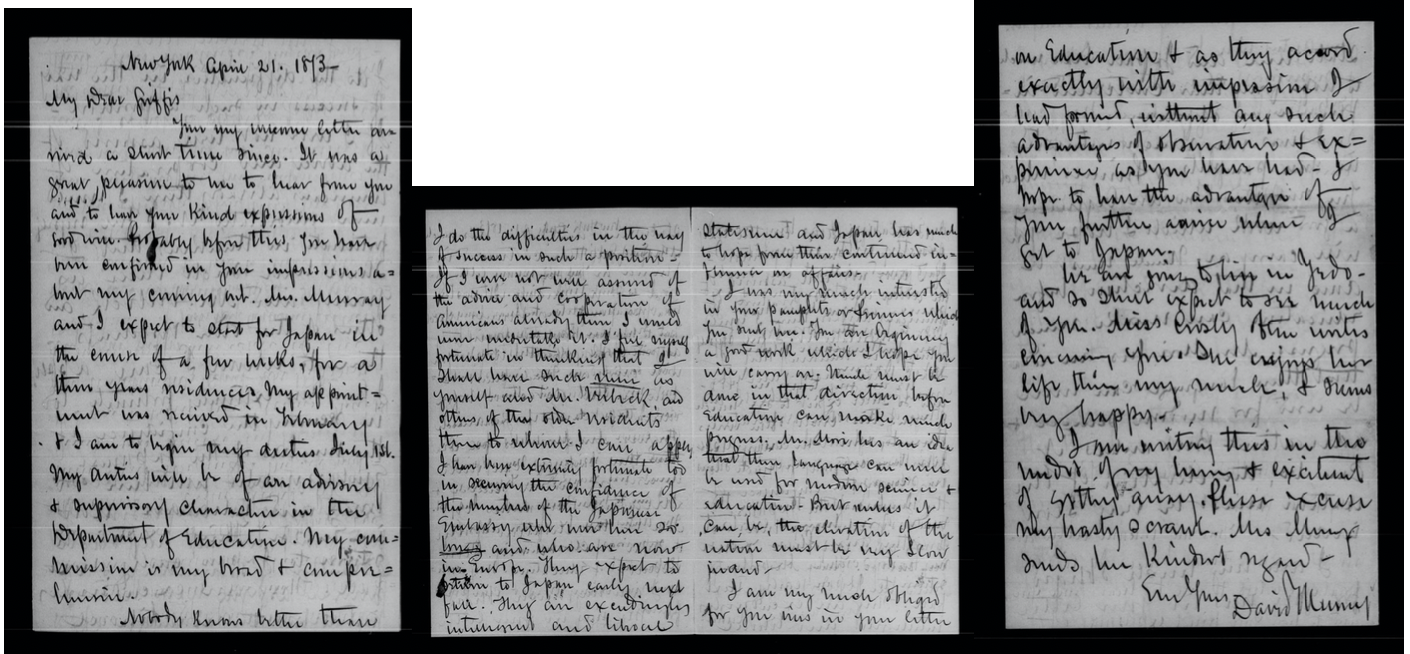

The article Paradox in Education written by William Elliot Griffis, discusses the growing results of “Occidentals,” or Westerners’ successful influence on Japan during the Meiji Period. He reflects quite early on in the era that the education that the West has provided was developing Japan and its people into a more superior race in comparison to the nations proximal to the country. The advancements in the military branches were one of the earliest recognized changes, with education recognized not very long after. Griffis discusses that the original superstitions and traditions that the Japanese created in earlier eras do not cloud their newly found Western education, which consisted of the sciences and medicine, as well as law and literature. However, this newly learned information would not have been utilized in such an advanced way if it was not for the Japanese people’s habit to meditate. Allowing them to separate intellect and emotions was something that had already been domestic to the people, and one of the main reasons Griffis believed that the Japanese were able to become so advanced so quickly.