Perry’s Arrival and the Opening of Japan

Introduction:

The pathstones to William Griffis’ journey to Japan were laid out years before he had even met Kusakabe Taro ’70. In the 1600’s, the Japanese shogun put an isolation policy into effect over the Japanese sovereignty. This was broken about 200 years later, on July 8, 1853, by Commodore Matthew Perry, an American naval officer. Breaking the Japanese horizon with his infamous “Black Ships,” Perry arrived with a small fleet, and was met with very conflicted opinions from the Japanese. While some felt it was time to open their shores to the Western world, the majority antagonized the thought of foreign influence. Regardless of widespread Japanese discontent, the cracks in Tokugawa Japan were slowly being chipped away at by the driving force of Westernization—a force that was strengthened by the 1859 arrival of missionaries such as Guido Verbeck, the first missionary to Japan from the Dutch Reformed Church, soon after the opening of Japan. Students from Verbeck’s English language school in Nagasaki were the first Japanese students who studied abroad, among whom were those who came to Rutgers. The opening of Japan also triggered the Meiji Restoration of 1868, in which the Tokugawa Shogun was overthrown, and power was restored to the Emperor. This marked the beginning of the rapid modernization and Westernization of Japan.

Griffis’ arrival in 1871 in Japan was also made possible by the 1860 Japanese Embassy to America, which familiarized Japanese government officials with what “Westernization” entailed. Armed with the accounts of Katsu Kaishu and others regarding American governmental structure and race relations, Japanese progressives eventually became comfortable enough with sending young samurai to the US (albeit without bakufu approval), not only to learn under American tutelage, but also to gain insights on the American education system. The first of the Japanese students, the Yokoi brothers, came to Rutgers in 1866, followed by Kusakabe in 1867. By 1870, a group of Japanese students, including sons of Katsu Kaishu and another prominent leader Iwakura Tomomi, were in New Brunswick, attending the Rutgers Grammar School or Rutgers College. The result: enough confidence for the Japanese to send a personal invitation requesting the services of a Western educator in Fukui. In 1872 the government was able to put together the Iwakura Mission, in which the nation’s most progressive leaders were able to bring back perspectives on Christianity and Western co-ed education. In addition, David Murray, professor of Rutgers College, was invited to Tokyo as the Superintendent of Education. Ultimately the collective educational reform efforts of Griffis, as well as Mori Arinori, David Murray, Tanaka Fujimaro, and Hatakeyama Yoshinari ’71 eventually culminated in Japan’s modern education system.

Click the following images to view an enlarged version.

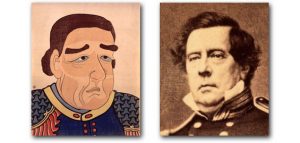

1853 Perry and the “Black Ships” Arrive

(Right) Daguerreotype by Mathew Brady from the Library of Congress, 1856

This caricature of Perry, among many others, illustrates the unfamiliarity of the Japanese with Westerners. Large eyebrows, noses, and eyes were among a few of the stereotypes perpetuated by Japanese artists during this time.

This chaotic scene at Edo bay unfolds after Perry’s “Black Ship” breaks through the Japanese line of defense. The unannounced arrival of these Americans revolved around an intimidation factor and likely contributed greatly to the Japanese portrayal of Westerners as demons.

Though Westerners were not yet in every part of the country, Okada remarks, the older Japanese demographic had mixed reviews about them. From believing Westerners to be servants who discover “wonderful machines and important things” for the Japanese, to viewing them as a religious threat, the elders in Japan had mixed opinions as to whether future generations should embrace Westernization. Click here to read more accounts of Japanese students’ first impressions of Westerners, and here to look at Meiji prints depicting Westerners.

1860 Embassy

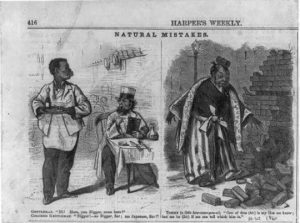

Despite the harsh racism that Japanese individuals in America experienced, Japanese boys and men were sent to study at Rutgers College to help Japan better understand Western education, which would later lay the foundation for co-ed learning and opportunities for females to study abroad. Ironically, the Japanese placed themselves at the top of the race hierarchy and were very vocal about it in their writings.

This time as the visitors in a much tamer setting, the Japanese are hosted at the White House by President James Buchanan, marking one of the first major instances of American-Japanese diplomacy on U.S soil. Just as the Japanese made the physical features of Westerners very glaring in their illustrations, so too did the Americans, portraying the ambassadors as shorter and darker.

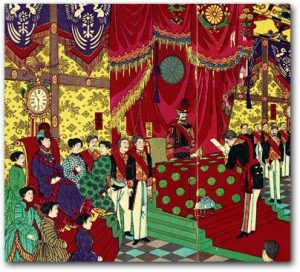

1868 Meiji Restoration

The Meiji Restoration brought about an end to military control under the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1868. This period led to major economic and social policy changes, including a growth in transportation, industry, and communication. Soon after the restoration, the first Japanese railroad was built (1872).

“Illustration of the Ceremony Promulgating the Constitution,” artist unknown, 1890 (detail) [2000.226]. Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

1872 Dr. Murray and the Modernization of Japan’s Education

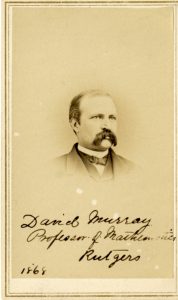

Tanaka Fujimaro, former samurai of Nagoya, and head of the Ministry of Education in Japan was responsible for surveying the Western education system in the United States during the Iwakura Mission from 1871 to 1873. During this time, Tanaka met Dr. David Murray, mathematics professor at Rutgers College. Dr. Murray signed a contract with Tanaka to offer his services to the Japanese Ministry of Education and to “take charge of all affairs connected with Schools and Colleges.” Tanaka and Murray worked side by side in developing an educational administration, teacher education plans, curriculum, universities, and financial plans. One of Murray’s major contributions to the Japanese Education System and arguably his largest, was the implementation of women as teachers in schools. Murray knew that women were better suited to deal with children, and their patience was superior to mens’. About a year and a half later, on October 31, 1875, the Tokyo Teacher Training School for Women (Tokyo Joshi Shihan Gakko) was opened.

“David Murray, Professor of Mathematics Rutgers,” from the William Griffis Collection, 1868

With the students and faculty of The Imperial University barely fitting into the picture, the university’s emergence is an auspicious sign for the future spread of education in Meiji Japan. The amount of university students pictured here outnumbered those at Rutgers College, which had only roughly 50 students as an established educational institution.

Exhibit created by Devin Busono (’22) and Raj Malhotra (’22)

-

Dower, J., 2010. Black Ships And Samurai. [online] MIT Visualizing Cultures. Available at:

<http://visualizingcultures.mit.edu/black_ships_and_samurai/bss_essay01.html>

[Accessed 7 May 2020].

Miyoshi, M. (1979). As we saw them : the first Japanese Embassy to the United States (1860) .

Berkeley: University of California Press.

Nish, Ian. The Iwakura Mission in America and Europe : a New Assessment . Japan Library,

1998.