Anita Hotchkiss

September 23, 2019

BLOG POST

CANTO V, LA DIVINA COMMEDIA, DANTE

For this Blog Post, I have chosen to compare the translation of Charles Rogers (1782) and that of Charles Eliot Norton, written 150 years later in 1902, and will discuss briefly two instances in which they differ from each other and, additionally, how they differ from Dante’s original.

Given that Rogers’ translation was written nearly 240 years ago, even its spelling is rather archaic for a current reader, the letter “s” being represented by the letter “f.” Nonetheless, once the reader mentally compensates for this spelling, it is surprising how easy the translation is to understand. Perhaps that is because, although both are written in free verse, Roberts makes no effort to respect Dante’s rhyme scheme or even his triplet verses, and the lines of his translation are numbered in “5s” rather than Dante’s “3s,” so if one wishes to match them up with Dante line for line, it is quite difficult to do so. For example, Rogers compresses Dante’s six lines 7-12

Dico che quando l’anima mal nata/li vien dinanzi, tutta si confessa;/e quel conoscitor de le peccata//vede qual loco d’inferno è da essa;/cignesi con la coda tante volte/quantunque gradi vuol che giù sia messa.

into five lines:

Whene’er a guilty Soul before him comes,/It all confesses: He the proper place,/Well knowing, that of Hell’s to be their due/, so many times his Tail around him twists/, As the Degrees to which he’d have it cast.

He makes this same compression many other times, and omits Dante’s words, sometimes for no reason which I can discern. (E.g. in the example above, he omits entirely Dante’s words “Dico che.”)

Like Rogers, Norton’s free verse translation ignores Dante’s rhyme scheme and triplets completely. However, in many ways his translation is more literal than Rogers’. He translates the above two stanzas as:

I mean, that when the ill born soul comes there before him, it confesses itself wholly, and that discerner of the sins sees what place of Hell is for it; he girds himself with his tail so many times as the grades he will that it be sent down.

Another instance of a difference between the two translations and where each suffers, I believe, a significant loss from the original is in Dante’s description of the moment in which Francesca da Rimini and her lover consummate their illicit union. In l. 133-138, Dante describes that when the two read of how Lancelot kissed Guinevere’s smile, Paolo kissed her and “quel giorno più non vi leggemmo avante.” (l.138). Rogers translates this as “But from that day we never read in’t more” which, in my view, mis-translates the passage and misses the meaning – that kiss ended their reading and led to lovemaking. Norton is somewhat closer to Dante, translating the passage as “that day we read no farther in it.” Mandelbaum, on the other hand, translates the passage “that day we read no more,” which I believe captures Dante’s meaning much better than either Rogers or Norton.

Another reflection of the 120 years between these two translations is the fact that the Rogers translation contains no notes, whereas Norton’s translation is interspersed with notes explaining many of Dante’s cultural references. This is perhaps recognition that Rogers’ target audience, 18th century presumably well-educated persons, were culturally attuned to and knowledgeable about Dante’s many references to historical and mythical figures. This was, after all, the era in which well-educated Englishmen took the Grand Tour, travelling to the continent and particularly to Italy, to experience in person European art, music, architecture, literature, and sculpture. Rogers dedicated his translation to “The Right Honorable Sir Edward Walpole,” who was the second son of Sir Robert Walpole, the first Prime Minister of Great Britain, and Edward undertook the Grand Tour in Italy at age 24, “lasting a number of years, as was the fashion.” (David Nash Ford’s Royal Berkshire History)berkshireshistory.com/bios/ewalpole.html).

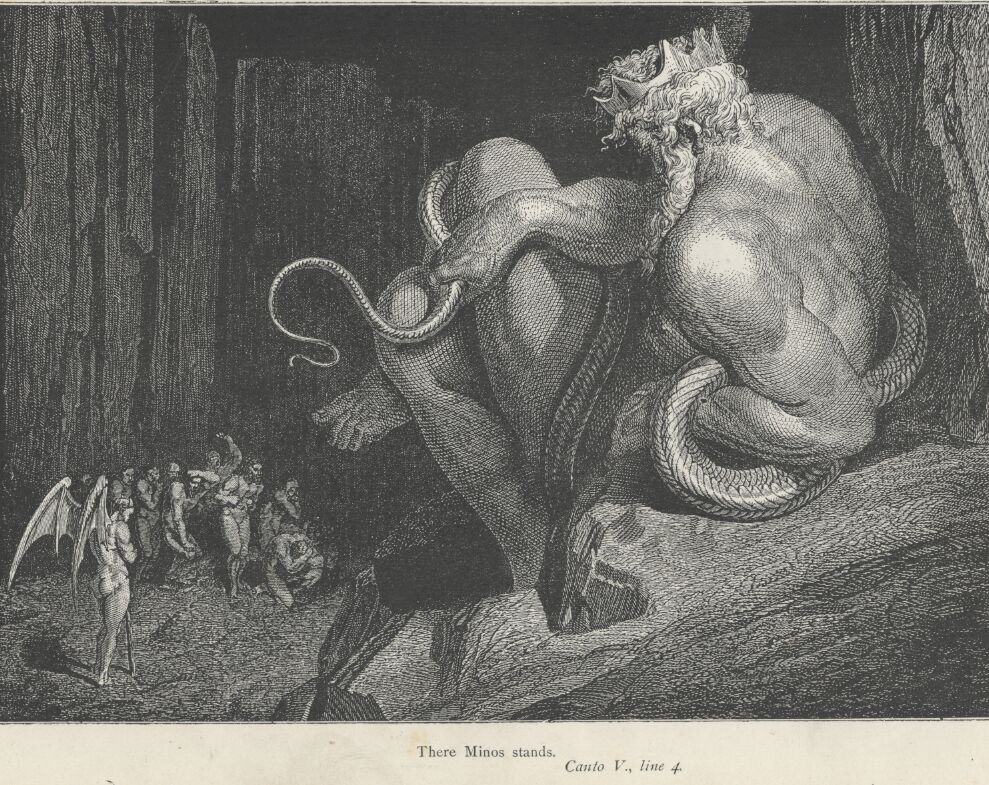

In sum, I believe that both these translations present the gist of Canto V quite well, although Norton is closer to the original and somewhat more understandable to a current English reader, especially with the addition of Norton’s notes, although even he did not feel it necessary to explain the identity of Minos or his role in the Inferno. The follow is an interesting illustration of Minos, as he wraps his tail around him, judging the location in hell to which he will send the lustful sinners for all eternity. In Greek mythology Minos was the first King of Crete, son of Zeus and Europa. After his death, Minos became a judge of the dead in the underworld. (Wikipedia)