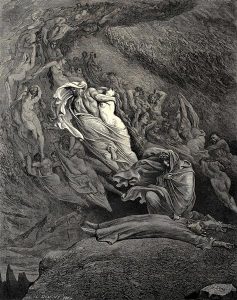

Canto 5 is, more or less, a speculation on the divergences between love and lust. Set in the second circle of hell, Dante’s fifth installment in his Inferno is characterized by much darker descriptions of suffering. However, Canto 5 draws heavily upon famous biblical and mythological (pagan) figures in the same way the former and latter Cantos do. This, paired with his direct identification of characters from his personal life, asserts Canto 5 as a significant piece in the literary and cultural tradition.

with his direct identification of characters from his personal life, asserts Canto 5 as a significant piece in the literary and cultural tradition.

Such significance, expressed through Dante’s particular word choice, verse structure, and sentence structure makes translating Canto 5 a considerable challenge. Choices must be made and losses/compromises accounted for. By looking distinctly at two translations, those of Charles Eliot Norton and Patrick Bannerman, such generalizations may become evident.

In short, both translations do a proper job of conveying the main themes woven throughout Canto 5. Circle two is rather evidently the circle of carnal lust. Here, the reader is introduced to a terrifyingly glorious place in hell where true punishment is expressed. Yet, in order to express such imagery and messages, Norton’s 1902 translation and Bannerman’s 1850 translation diverge. Primarily, the two translations differ in terms of the formality of language used. Whereas Bannerman opts to use more dignified or proper words, Norton keeps his word choice far simpler and elementary. It may be useful to point out that this may be in part due to the periods of time in which the authors wrote their translations. Norton’s translation comes almost half a century before Bannerman’s. Additionally, the translations differ in terms of the medium used. Interestingly, Norton chooses prose over poetry.

Due to differences between the two translations, there are evidently pros and cons to both. For instance, in Bannerman’s translation, he introduces Minos as “grinding his teeth horribly,” whereas Norton regards him as simply snarling. If one is to look at Dante’s “ringhia,” then Norton’s take is much more closely aligned to what Dante meant. Bannerman chose to invent rather than interpret, which may come across as problematic. Similarly, Norton translates Dante’s “galeotto” as “Galehaut,” who acted as an intermediary between Lancelot and Guinevere in the Arthurian legend. This translation seems to be more effective than Bannerman’s “Galeotti” which lacks context and thought. For a reader such as myself, identifying Galehaut makes the reference far clearer.

Due to differences between the two translations, there are evidently pros and cons to both. For instance, in Bannerman’s translation, he introduces Minos as “grinding his teeth horribly,” whereas Norton regards him as simply snarling. If one is to look at Dante’s “ringhia,” then Norton’s take is much more closely aligned to what Dante meant. Bannerman chose to invent rather than interpret, which may come across as problematic. Similarly, Norton translates Dante’s “galeotto” as “Galehaut,” who acted as an intermediary between Lancelot and Guinevere in the Arthurian legend. This translation seems to be more effective than Bannerman’s “Galeotti” which lacks context and thought. For a reader such as myself, identifying Galehaut makes the reference far clearer.

In my view, I see Norton’s translation as the more effective translation—especially for a contemporary American reader. Because Norton does not try and force the terza rima of Dante, he is not boxed into the awkward syllabic pattern that Bannerman is. Norton is also able to avoid being tempted to use rhetoric that may not necessarily convey what Dante meant simply because it sounds right to the ear. Ultimately, I personally do not feel like Norton’s translation is lacking because it misses the swing of a metre. Instead, it surpasses Bannerman’s because it gives a clear and coherent conveyance of Dante’s work.

In conclusion, it is up to the discretion of the translator to determine which elements of any piece of work are the most necessary to preserve. When it comes to literary canons such as Dante, even the most practiced and well-versed translators run into difficulty. Medieval Italian and contemporary English are not necessarily compatible. Likewise, Dante does not shy away from contemplating some of the most challenging theoretical concepts. His works, as Bannerman and Norton prove, are no easy, (translational) feat.