Puerto Rican New Yorkers: The Communist Party and the Hispanic Popular Front

During the 1930s, well-known Puerto Rican leaders Jesus Colon and Bernardo Vega—but also hundreds of others—transitioned from supporting the Socialist Party (which had been the center of working class politics among Hispanics in New York) to the Communist Party. They were encouraged by the aggressive and persistent grassroots organizing and militant rhetoric of mobilization that characterized the Communist Party’s response to the Depression in New York. The move was also propelled by the failures of Puerto Rico’s Partido Socialista and the radicalization of labor politics on the island itself. Colon and Bernardo Vega were not the initial leaders of this transition. A small cadre of working class Puerto Ricans (and other spanish speakers) were already present in the Communist Party since the late 1920s and served as a bridge to the new members. The populist and reformist turn of the Communist Party that started in the mid-1930s and the successes of unionization and relief fights broadened further the appeal and recruitment among Puerto Rican workers and made the Communist-led (and inspired) Popular Front politics the political center of Hispanic progressivism, what I call the “Hispanic Popular Front”.

One of the first Puerto Ricans to join the Party through contact with its Harlem-based locale (the Centro Obrero de Habla Española) was Frank Ruiz. Ruiz migrated in 1923 by working on a ship as a mess boy. He then worked as a power press operator at a tin can factory while studying at night. He joined the Communist Youth and soon after the Party itself (as well as one of the Hispanic clubs of the International Workers’ Order), where he worked with Juan Aviles, Armando Ramirez, Consuelo Marcial, and Alberto Sanchez.[1] Juan Aviles and Alberto Sanchez were active in southern Harlem and presented as candidates by the Party’s Spanish Speaking Section in 1930.[2] Sanchez was probably the Puerto Rican with the longest history of work within the Party, having worked in a factory in Brooklyn since 1926. Before he moved to New York, Sanchez had already done two years of political work in Colorado among Mexican Americans.[3]

In 1930, the Communist Party’s Hispanic Section launched a campaign to recruit Puerto Ricans through its branches and newspapers. In the October 27, 1930, issue of Vida Obrera, editors bragged about how it was the only party to have an anti-imperialist platform dedicated to the absolute independence of Puerto Rico.[5] The Party’s strong positions that demanded relief from Depression-era conditions, attracted many Puerto Ricans, Cubans and Spaniards who often had participated in militant labor unionism.The Party’s paper made these needs and frustrations clear. A letter from a WWI veteran from the Bronx, most likely a Puerto Rican (most Spaniards and Cubans were not citizens and thus did not serve in WWI) decried how he had volunteered to fight his class brothers in France and now found himself in “una vida perra, enfermo, sin dinero, sin ropa, sin nada.”[6]

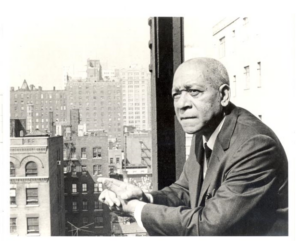

Jesus Colon soon became the best-known leader of the Communist Party’s Spanish-speaking section, but he was accompanied by dozens of other organizers. From his roots in Puerto Rico’s Partido Socialista and US Socialist Party politics, he transitioned to the Communist Party’s orbit in the early 1930s. Colon eventually became arguably the most important leader of the Party’s Spanish Section and director of the International Workers Order’s Hispanic mutual aid and social clubs, which later were named the Cervantes Society. From these positions (and others) Jesus Colon was a tireless fighter for working class issues and the rights of Spanish-speaking communities.

Like Jesus Colon, hundreds of other Puerto Ricans (and many Cubans and Spaniards) joined the Communist Party, and thousands joined or supported the Internatioanl Workers Order (IWO) clubs, the American Labor Party (and many related movements and organizations) because they provided a vehicle for them to make demands for their economic wellbeing and for the expression of their needs as ethnic (and racial) subjects. Many saw themselves as militant revolutionary anti-capitalists or socialists, but most were reformists with an orientation towards working-class goals and solidarity. That these movements led by “Communists” and “Socialists” worked within the broad limitations of reformist New Deal politics and the Stalinist opportunism of the Communist Party cannot be denied. Essentially, the Communist Party’s Popular Front politics expressed a form of Democratic Socialism that hinged on accepting a capitalist framework to push for strong reforms favoring working-class people. Unlike the Socialist Party, which had sustained a tradition of political autonomy, the Communist Party pursued strategic rhetorical and electoral support for national Democratic Party (and some Republican Party candidates) progressives and reformers in an effort to fight what they saw as their main enemy, internal and external fascism (which often slipped into a simplistic vision of rule by corporations). This framework created opportunities as well as obstacles for the Latino working class and Puerto Rican activists. For Latinos and especially colonial-origin, US-citizen Puerto Ricans, the culturally inclusive, reformist, and alliance-building politics of the leftist Popular Front world had a special attraction, and in engaging with these struggles, they extended to New York’s growing Hispanic spaces, the shared progressive politics of the Hispanic Popular Front.

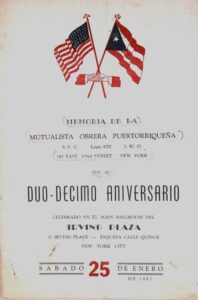

The intersection of the Communist Party with New York’s Puerto Rican and larger Hispanic communities produced a network of Spanish-speaking lodges and clubs affiliated with the Communist Party’s International Workers Order. Led by Jesus Colon, Consuelo Marcial, Jose, and Emilia Giboyeaux, and many others from the Party’s Hispanic Section and joined by many progressively-minded community leaders, the Hispanic lodges of the IWO built a magnificent movement that formed the core of what I call the Hispanic Popular Front. The IWO was established in 1930 by the Communist Party as an insurance and fraternal organization that would help workers survive the Depression and develop a culture of working-class solidarity. Their goal was to agglomerate the many community and solidarity-oriented mutual aid societies of the immigrant and ethnic communities during desperate economic insecurity and lack of health, unemployment, or death benefits.[8]

The intersection of the Communist Party with New York’s Puerto Rican and larger Hispanic communities produced a network of Spanish-speaking lodges and clubs affiliated with the Communist Party’s International Workers Order. Led by Jesus Colon, Consuelo Marcial, Jose, and Emilia Giboyeaux, and many others from the Party’s Hispanic Section and joined by many progressively-minded community leaders, the Hispanic lodges of the IWO built a magnificent movement that formed the core of what I call the Hispanic Popular Front. The IWO was established in 1930 by the Communist Party as an insurance and fraternal organization that would help workers survive the Depression and develop a culture of working-class solidarity. Their goal was to agglomerate the many community and solidarity-oriented mutual aid societies of the immigrant and ethnic communities during desperate economic insecurity and lack of health, unemployment, or death benefits.[8]

By 1937 the Hispanic Popular Front, with the IWO lodges at its center, was growing quickly. The Communist Party’s Spanish Section had grown and established itself as the most active and dynamic political organization in the Spanish-speaking neighborhoods, in competition (and sometimes collaboration) with the small Hispanic Socialist, Democratic, Republican, and eventually Liberal Party clubs. The IWO lodges and clubs were expanding both in number and size. Independent socialists, radicals, and progressives agglomerated in these clubs around support for Roosevelt’s New Deal and Good Neighbor policies, the emerging industrial labor movement, and support for the global anti-fascist struggle. But no other single issue besides conditions in Puerto Rico mobilized more Puerto Rican and pan-Latino support than the defense of the Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil war (1936-1939). Support for the Republic became a common part of progressive and leftist mobilization. The fight against fascism in Spain presented two important elements that connected Puerto Ricans, Cubans and Spaniards in New York: the Popular Front encouraged the defense of a vision of progressive Hispanism that had deep cultural roots among Puerto Rican activists and leaders who had sought to use language, and a larger Hispanic ethnic identity as one basis for establishing solidarity and support for progressive labor politics among Latinos in New York.

Popular Front leaders and organizations, with various levels of proximity to the Communist Party, also produced a vibrant leftist press between the early 1930s and the mid-1940s. Different iterations of Communist Party-supported newspapers, from Vida Obrera through Pueblos Hispanos, Liberacion, and La Voz, gave voices to the political and cultural (and even commercial) interests of the Spanish-speaking, left-leaning community. Commercial newspapers like El Diario and La Prensa were also pushed to cover the labor and left news emerging from the Latino communities in these years.

Popular Front leaders and organizations, with various levels of proximity to the Communist Party, also produced a vibrant leftist press between the early 1930s and the mid-1940s. Different iterations of Communist Party-supported newspapers, from Vida Obrera through Pueblos Hispanos, Liberacion, and La Voz, gave voices to the political and cultural (and even commercial) interests of the Spanish-speaking, left-leaning community. Commercial newspapers like El Diario and La Prensa were also pushed to cover the labor and left news emerging from the Latino communities in these years.

Another important component of Popular Front politics among Latinos was the American Labor Party. The ALP was created in 1936 to mobilize leftist support for the New Deal and to elect left-leaning candidates to local elections (and against Tammany Hall interests) at a time when the popularity of the Communist Party was growing markedly, and the Socialist Party was in crisis.[6] It was a product of New York’s politicized unions, and only in New York did the ALP become a significant force for votes and protest mobilizations. Initially supported by the Socialist Party, the Communist Party, and the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) leadership, the ALP came more fully into the orbit of the Communist Party in 1944. The ALP was able to mobilize significant levels of support despite the exit of the Social Democrats and others who had grown disaffected with the steamroller style of the Communist Party. It served as the basis for Vito Marcantonio, a leftist congressman from East Harlem, electoral successes. Vito Marcantonio represented East Harlem in Congress and was singularly dedicated to his Italian and Puerto Rican working-class and poor constituents.[7] He supported Puerto Rican independence and defended Albizu Campos, the Nationalist Party, and the Partido Independentista. The ALP also helped elect the first Puerto Rican to govern as part of the New York State Assembly. The ALP fielded many Puerto Rican candidates and mobilized people for hundreds of protests and other efforts from the late 1930s through the early 1950s.

Despite auspicious beginnings as part of the pro-Henry Wallace campaign of 1948 (which received participation from the Hispanic Popular Front activists including Bernardo Vega and Jesus Colon), after that year the Hispanic Popular Front declined like much of the leftist culture and organizing in New York. The victim of red-baiting, red-scare, and cold war politics, it also suffered from the limitations of the Communist Party’s strange combination of liberalism and Stalinism and its inability to create a political movement that was independent from mainstream parties. The New York State Attorney seized the IWO and most of the clubs and lodges closed as members withdrew in fear. For Puerto Ricans the risk of associating with the left was now doubly dangerous, as state agencies policed leftists at the local and national levels, and the repercussion of the Korean War (which began in 1950 with tens of thousands of Puerto Rican troops) and the 1950 Nationalist attack on Truman’s Blair House. Stalin’s crimes, his contradictory and often treacherous role in the Spanish Civil War, and the reality of the murderous counterrevolution that he had led in the Soviet Union were not important, as they were not well known to most Puerto Ricans or broadly to most supporters of the left. The anti-communist hysteria of the 1947-1960 years was the most important reason for Puerto Ricans to distance themselves from leftist politics. Puerto Rican leaders were questioned about association with “Communist” entities by congressional investigations and the FBI, and labor leaders were subjected to the scrutiny of anti-leftist purges and even legal requirements. The Communist Party itself nearly ceased to exist, and many of its members were driven into hiding. The ALP, by then controlled entirely by the Communist Party for electoral purposes, ceased to exist in 1956.

The text is copyrighted by the author, 2025. Images by Permission of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies, 2019.

Users may cite with attribution.

[1] Various, Communist Party of the USA, Collection 132, Tamiment Library and Wagner Archive, New York University.

[2] Vida Obrera, 22 September 1930; 13 October 1930.

[3] Vida Obrera, 8 June 1931.

[4] Vida Obrera, 27 October 1930.

[5] Vida Obrera, 27 October 1930.

[6] Shannon, David A. The Socialist Party of America: A History. New York,: Macmillan, 1955.

[7] Meyer, Gerald. Vito Marcantonio: Radical Politician, 1902-1954. State University of New York Press, 1989.