Puerto Rican New Yorkers: The Anti-Discrimination Establishment in the 1940s-1960s

In the years after World War II, New York was the most advanced state in anti-discrimination legislation and had a robust anti-discrimination establishment of organizations focused on equal rights for Jews and Blacks. When Congress refused to extend the wartime FEPC legislation, New York State enacted its own through the Ives Quinn bill which banned discrimination on the basis of color, religion, language, and national origin.[1] It followed on earlier efforts dating back to the 1930s banning discrimination in more restricted domains (i.e., public employment, public spaces, defense work, tax exempt entities).[2] The legislation was broad enough to reflect New York’s immigrant diversity. The legislation initially focused on work but was later extended to housing through the Sharkey Brown bill of 1950, and additional refinements to the law that created the New York State Commission Against Discrimination (SCAD). The establishment that came out of this legislation brought together Catholic, Jewish, and Black organizations and leaders, liberals and republicans. Much of the impetus in New York was the result of Jewish struggles since the 1930s to make discrimination illegal. The fight against local and European anti-Semitism was also an important aspect of this struggle, sharing strong antifascist politics that united Left and liberals but made it an easy target of the Right. Jewish groups were also strong supporters of the FEPC and its continuation after the war.[3]

In the years after World War II, New York was the most advanced state in anti-discrimination legislation and had a robust anti-discrimination establishment of organizations focused on equal rights for Jews and Blacks. When Congress refused to extend the wartime FEPC legislation, New York State enacted its own through the Ives Quinn bill which banned discrimination on the basis of color, religion, language, and national origin.[1] It followed on earlier efforts dating back to the 1930s banning discrimination in more restricted domains (i.e., public employment, public spaces, defense work, tax exempt entities).[2] The legislation was broad enough to reflect New York’s immigrant diversity. The legislation initially focused on work but was later extended to housing through the Sharkey Brown bill of 1950, and additional refinements to the law that created the New York State Commission Against Discrimination (SCAD). The establishment that came out of this legislation brought together Catholic, Jewish, and Black organizations and leaders, liberals and republicans. Much of the impetus in New York was the result of Jewish struggles since the 1930s to make discrimination illegal. The fight against local and European anti-Semitism was also an important aspect of this struggle, sharing strong antifascist politics that united Left and liberals but made it an easy target of the Right. Jewish groups were also strong supporters of the FEPC and its continuation after the war.[3]

The State Commission against Discrimination was created to enforce anti-discrimination legislation. SCAD carried out aggressive public propaganda work, including in Spanish-language media and organized local Community Councils. It also scoured the constitutions and rules of high-skill unions, demanding that the ‘Caucasians only’ clauses be eliminated. It pushed employment agencies and hiring practices to remove the common race or religion-specific, discriminatory language in job advertisements.[4] The Commission had some legal powers but its preferred method was pressure, conciliation and negotiation, accepting the limitations of its form by accepting seniority and apprentice practices that resulted in discrimination.[5]

Few Puerto Ricans had made use of SCAD’s authority in the immediate post-war years. Many community leaders thought that Puerto Ricans shared a cultural apprehension against acknowledging or complaining about discrimination. Writer Jack Agueros put it in these terms: “this pride and value of integrity is ancient. You can find it in El Cid, in the plays of Lope de Vega, in don Quixote. And you find it among the Puerto Ricans today. In America it debilitates them, it keeps them from filing complaints of violation of human and civil rights, from contesting employers’ decisions before state referees and state agencies.”[6]

SCAD’s means to end large-scale employment discrimination were limited. Even though it had enforcement and mediation (as well as education) functions, its broad scope and weak enforcement context meant that it managed only limited inroads that relied on shame and visibility, especially with discrimination against blacks. Initially, it depended upon the injured to file complaints and remain present through the investigation process. Most of its complaints involved discrimination against Jews and Catholics. It’s visibility and budget increased over the years as black leaders fought to ehance its functions throughout the 1950s. Later in the decade SCAD carried out its own major investigations of discrimination in a systemic, industry-focused way and in many ways foreshadowing what federal anti-discrimination legislation would look like in the 1960s under the Civil Rights Act (1964) and the Equal Employment Opportunity Act (1972).

The sharpest teeth for anti-discrimination work in the courts would not appear until the 1960s when New York State legislation authorized district attorneys to work with SCAD to pursue lawsuits against employers and unions. The politics of SCAD were not without controversy. Many civil rights leaders and organizations thought that SCAD was timid (like Herbert Hill, labor director of the NAACP), or that it should have been headed by an African American.[7]

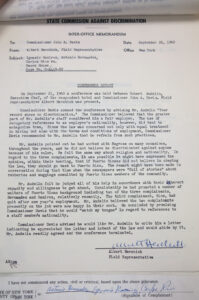

Charles Abrams, appointed to lead SCAD in 1955, pursued labor issues more aggressively and reached out more consistently to the Puerto Rican community. Through the mid-1950s, of the 400 yearly complaints handled by SCAD, 10% were by Puerto Ricans.[8] SCAD would play a bigger role in the lives of Puerto Rican workers after 1955. For the first ten years, 70% of complaints involved color discrimination. Of 5,225 complaints filed in these ten years, 300 were filed by Puerto Ricans. But after 1956 42% of the complaints were over national origin, overwhelmingly Puerto Rican, with 266 complaints filed in just four years (1955-1958) when Puerto Ricans also asserted their claims for support and attention from the City’s labor movement.[9] The vast majority of complaints by Puerto Ricans were over workplace discrimination (90%) and mostly by factory operatives, unlike those filed by Jews, blacks, and Italians, which originated in housing complaints and white-collar jobs.[10]

Nicolas Guadalupe filed a complaint (in what he acknowledged was imperfect English) with SCAD in August 1958. Guadalupe wrote that he represented many others who could not speak English: “This not a protest, not an accusation or a mutiny, we are just using our democratic rights, as American citizens.” He complained of how Italian Americans treated them, writing, “Why do they have the better jobs, why can’t we get a job as decent as theirs. Why Eastman Kodak don’t hire no Spanish speaking personnel?” Why did the problems caused by one Puerto Rican create trouble for all of them? “This a “democracy” and such things shouldn’t happen in a democratic country. Remember this, during the II World War and in the Korean War we did fight for the democracy cause. Lots of Puerto Ricans died in those foreign soils, all for the sane cause.” He had tried finding work at Gerber’s but found that only Italians got hired. And Puerto Rican rents were higher, apartments hunters were rejected as soon as they said they were Puerto Rican. “We wish we could see you personally to explain you lots of things more. But as we told you before our main problem is jobs, jobs, jobs, we are humans, we got to live someway.”[11]

It was the needs of rebellious Puerto Rican workers that pushed SCAD to add a Labor Advisory Committee in December 1956.[12] ILGWU Local 22 president Charles Zimmerman was named labor advisor to SCAD’s Labor Committee, with Jose Sanchez of the Amalgamated Laundry Workers joint board and David Livingston of District 65.[13] Zimmerman was among the most important Jewish union leaders involved with Puerto Rican working-class issues.The contact and negotiation between Abrams of SCAD and these labor leaders was ongoing.[14] By the mid-1950s, journalists in the Spanish press knew to refer workers’ complaints to SCAD and the Migration Division.[15] The Migration Division also translated some of the published or radio work created by SCAD.[16]

It was the needs of rebellious Puerto Rican workers that pushed SCAD to add a Labor Advisory Committee in December 1956.[12] ILGWU Local 22 president Charles Zimmerman was named labor advisor to SCAD’s Labor Committee, with Jose Sanchez of the Amalgamated Laundry Workers joint board and David Livingston of District 65.[13] Zimmerman was among the most important Jewish union leaders involved with Puerto Rican working-class issues.The contact and negotiation between Abrams of SCAD and these labor leaders was ongoing.[14] By the mid-1950s, journalists in the Spanish press knew to refer workers’ complaints to SCAD and the Migration Division.[15] The Migration Division also translated some of the published or radio work created by SCAD.[16]

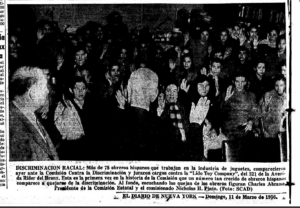

One notable intervention with Puerto Ricans was the mass protest against the Bronx Lido Toys factory in 1956 by 75 Puerto Rican women.[17] At Stellar Tool Manufacturing in Queens, 60 mostly Puerto Rican workers filed a complaint “charging that the Spanish workers were receiving wages far below that of the norm.”[18]

By the mid-1960s it would be Puerto Ricans running SCAD and COIR’s inheritors. SCAD became the State Commission for Human Rights, and Ruperto Ruiz, former SCAD investigator and founder of the Spanish American Youth Bureau, was appointed director. John Carro was hired as a legal investigator, while Juan Aviles and Juan Sanchez were appointed to positions within the CCRC.

The City of New York pursued a more local approach to racial and ethnic conflicts or discrimination. Mayor La Guardia had created a “committee on unity” which did little work relating to Puerto Ricans. Mayor O’Dwyer continued it. In 1950 officials asked O’Dwyer to add a Puerto Rican member, and Manuel Cabranes, first director of the Migration Division, became the committee’s first board member.[19] The Committee on Unity had little power and no funding—its entire budget of $5000 came from Rockefeller Jr. and other corporate donations. The CU handled cases of “neighborhood tension,” especially when blacks and Puerto Ricans began moving into formerly homogeneously white neighborhoods.[20] Inevitably, it was open to wrangling about representation between Black and Jewish organizations. Its relationship with Puerto Ricans was minimal while the Mayor’s Committee on Puerto Rican affairs existed; but when both were merged into the Commission on Inter-Group Relations (COIR) in 1958, its mandate expanded, and its Puerto Rican agenda and personnel grew as well.

The City of New York pursued a more local approach to racial and ethnic conflicts or discrimination. Mayor La Guardia had created a “committee on unity” which did little work relating to Puerto Ricans. Mayor O’Dwyer continued it. In 1950 officials asked O’Dwyer to add a Puerto Rican member, and Manuel Cabranes, first director of the Migration Division, became the committee’s first board member.[19] The Committee on Unity had little power and no funding—its entire budget of $5000 came from Rockefeller Jr. and other corporate donations. The CU handled cases of “neighborhood tension,” especially when blacks and Puerto Ricans began moving into formerly homogeneously white neighborhoods.[20] Inevitably, it was open to wrangling about representation between Black and Jewish organizations. Its relationship with Puerto Ricans was minimal while the Mayor’s Committee on Puerto Rican affairs existed; but when both were merged into the Commission on Inter-Group Relations (COIR) in 1958, its mandate expanded, and its Puerto Rican agenda and personnel grew as well.

For these public entities and the many private organizations, the challenges were daunting, as noted by recent histories of whiteness and the black Civil Rights movements in the North. Daniel Dodson, one of the prominent white activists against racism and head of the MCU, made a simple balance sheet on race relations in NYC in 1946.[21] On the positive side, New York City had the Ives Quinn act, the country’s first state anti-discrimination law, to work with, which (began to) “integrate” public housing and civil service, strong support for a meritocracy and “ideals of liberty and equality which are constantly violated but exist in our culture” and an infrastructure of anti-discrimination organizations. But the city also faced the reality of white racism: as expressed in surveys, half of white New Yorkers would not accept a black person as a friend, and an even higher percentage would not accept black neighbors. This, in conjunction with persistent anti-Semitism, created an economy that “did not meet people’s needs,” and which generated multiple hate groups and discriminatory practices.[22]

The most powerful anti-discrimination organizations coming out of WWII years were Jewish, and they would turn their attention to the problems of Puerto Ricans as their own communities became accepted as white, moved to the outer rings or suburbs, and abandoned a Jewish identity. In the following 15 years, Jewish organizations fought legal and political battles to end discrimination against Jews. But anti-black racism had deeper roots and was a more intractable problem for the mayor’s office.

The most powerful anti-discrimination organizations coming out of WWII years were Jewish, and they would turn their attention to the problems of Puerto Ricans as their own communities became accepted as white, moved to the outer rings or suburbs, and abandoned a Jewish identity. In the following 15 years, Jewish organizations fought legal and political battles to end discrimination against Jews. But anti-black racism had deeper roots and was a more intractable problem for the mayor’s office.

The City under Mayor Wagner, with less coercive power than the state and with a stronger focus on local community relations, developed a Committee on Inter-Group Relations (COIR) which focused on helping communities manage conflict and create integrated or anti-discriminatory organizations and events. COIR was Wagner’s attempt to mediate local conflicts, especially between blacks, Jews, and whites. It would hold hearings and design interventions, especially during crises, complaints of housing discrimination and youth conflicts. COIR reflected Wagner’s proactive liberalism on racial and labor conflicts, but also his preference for methods that emphasized unity. For this reason, he abolished the MCPRA and merged its functions into COIR. However, by 1956, Wagner had to establish a Puerto Rican issues committee within COIR in order to deal with the growing complaints and conflicts from the community. The mayor’s assistant explained: “the mayor is still of the opinion that American citizens who reside in New York, whether originally from Puerto Rico, Oklahoma, Alabama, or any other place, should have their problems treated in similar fashion.” However, it was clear that Puerto Ricans either merited or demanded more attention.[23] It was in COIR that Antonia Pantoja began her career in civil rights work. She was appointed to COIR in 1955 as a result of a massive letter-writing campaign to Wagner in June, when he abolished the MCPRA.[24]

COIR, like SCAD, kept in close contact with labor organizations, especially when they addressed civil rights and housing or social service needs, as well as the Migration Division of the PR Department of Labor.[25] In the post-war years, “Inter-group relations” was a language, a social science and social work approach and field, and a response by liberal politicians to racial and ethnic conflict.[26]

The COIR correctly emphasized that the “problem” of race was not simply a Black or Puerto Rican problem but one that lay in managed solutions involving all parties. With the new focus in the 1950s on abolishing discrimination in housing, the city had many opportunities to improve the options available to blacks and Puerto Ricans and to mitigate conditions. COIR faced a daunting task. Sometimes, it could minimize conflict and mediate agreements. Still, it could not wrangle either with the everyday insults that were the product of both racism and the ethnic tribalism of NYC social life, nor change the minds of the significant segment of New Yorkers who espoused white supremacist or nativist views. By the time COIR was renamed and restructured into the City Commission on Human Rights in 1965, Puerto Ricans had become a central focus of COIR’s work. The CHRC became a major player in trying to provide access to construction jobs for Blacks and Puerto Ricans in the 1960s. It also sponsored the “ethnic survey” of city employees in 1964. Gilberto Gerena Valentin was appointed to direct the CHRC in 1966.

The COIR correctly emphasized that the “problem” of race was not simply a Black or Puerto Rican problem but one that lay in managed solutions involving all parties. With the new focus in the 1950s on abolishing discrimination in housing, the city had many opportunities to improve the options available to blacks and Puerto Ricans and to mitigate conditions. COIR faced a daunting task. Sometimes, it could minimize conflict and mediate agreements. Still, it could not wrangle either with the everyday insults that were the product of both racism and the ethnic tribalism of NYC social life, nor change the minds of the significant segment of New Yorkers who espoused white supremacist or nativist views. By the time COIR was renamed and restructured into the City Commission on Human Rights in 1965, Puerto Ricans had become a central focus of COIR’s work. The CHRC became a major player in trying to provide access to construction jobs for Blacks and Puerto Ricans in the 1960s. It also sponsored the “ethnic survey” of city employees in 1964. Gilberto Gerena Valentin was appointed to direct the CHRC in 1966.

The anti-discrimination establishment was much bigger than the state and city agencies. New York’s’ working class and middle-class liberals and leftists had formed large networks of organizations and coalitions that expanded their efforts after WWII. On the west side of Manhattan, for example, the “west side committee on civil rights” created a broad multiethnic coalition of Civil Rights organizations. In 1949, their “Bill of Rights Day” included representatives from the Association for the Advancement of Puerto Rican people, the Spanish-American youth bureau, various Jewish and Catholic groups, the Negro Labor Committee, the Morningside Community Center, American Veterans Committee, B’nai B’irth, and sleeping car porters.[27]Similar coalitions appeared in parts of the Bronx and Brooklyn; and on Manhattan’s east side: the Committee on Civil Rights in East Manhattan, the Spanish American youth bureau, Black, Japanese, and Jewish chambers of commerce. They carried out a major campaign to research discrimination against blacks in restaurants in midtown, with of strategy of research, followed by ‘continuous pressure and negotiations,” and plans to move on to housing work.[28]

The largest anti-discrimination organizations were focused on Jewish and African Americans. Puerto Ricans would relate to these organizations in different ways, sometimes learning from the inside and other times seeking their support for their own efforts. Many Jewish leaders and organizations were supportive of Puerto Rican needs through the 1960s. Within labor organizations, in many local communities, mixed Puerto Rican and Jewish neighborhoods, and throughout, both explicitly Jewish organizations and of leaders of Jewish background, both liberal and leftist, abounded.

The text is copyrighted by the author, 2025.

Users may cite with attribution.

[1] Chen, Anthony S. “”The Hitlerian Rule of Quotas”: Racial Conservatism and the Politics of Fair Employment Legislation in New York State, 1941-1945.” The Journal of American History 92, no. 4 (2006): 1238-64.

[2] Jasinski, Arthur. “The Civil Rights of the Puerto Ricans in New York City 1946-1965.” Thesis (MA), St. John’s University, 1967.

[3] Dollinger, Marc. Quest for Inclusion: Jews and Liberalism in Modern America. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2000.

[4] New York State. State Commission Against Discrimination. New York State Protects Workers against Discrimination in Employment Because of Race, Creed, Color or National Origin. 1948 Report of Progress. New York, 1949.

[5] Biondi, Martha. To Stand and Fight: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Postwar New York City. Cambridge, Mass.; London: Harvard University Press, 2006.

[6] Jack Agueros, “Halfway from Dick and Jane, a Puerto Rican Pilgrimage,” in Agueros, Jack, and Thomas C. Wheeler, Eds. The Immigrant Experience: The Anguish of Becoming American. Pelican Books. Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1971, 88.

[7] “Continued Bias in Pier Hiring is Charged by 2 Negro Leaders,” The New York Times, 15 September 1959.

[8] “Charles Abrams dice problema de los boricuas en New York no tiene solución,” El Diario, 3 April 1956.

[9] Statement by Charles Abrams, Chairman of NY SCAD, Press Release, 3 December 1956, Box 159, Folder 10, Records of the Jewish Labor Committee, Series III, Wagner 025, Tamiment Library and Wagner Labor Archive, New York University.

[11] Einach to Guadalupe, 18 August 1958, Box 391, Folder 5, OGPRUS, Centro Archive.

[12] Newsletter of the State Commission against Discrimination, December 1956, 1:1.

[13] Minutes of the Labor Advisory Committee of SCAD, 9 January 1957, Box 159, Folder 10, Series III, Records of the Jewish Labor Committee, Wagner 25, Tamiment Library and Wagner Labor Archive, New York University.

[14] “Guerra contra el discrimen. Wagner y Harriman asisten a reunión de la comisión estatal,” El Diario, 8 May 1956.

[15] “Boricuas que quieren trabajar siempre encuentran un empleo.” El Diario, 6 May 1956.

[16] Radio dialogue from SCAD, Box 3003, OGPRUS, Centro Archive; Weekly Report, M. to Sierra Berdecia, 7 August 1957, Box 2948, OGPRUS, Centro Archive.

[17] “SCAD juramentan obreras contra Lido Toys.” El Diario, 11 March 1956; “75 Women Charge Bias,” The New York Times, 9 March 1956.

[18] ACTU Complaints Files, Collection RG1-027, Series 4, File 20/11, AFL-CIO Papers, Special Collections, University of Maryland.

[19] Arthur Wallander, Chairman of Committee on Unity to O’Dwyer, 25 May 1950, Box 36, Folder 339, Roll 18, Mayor’s Papers, New York City Municipal Archive.

[20] “Offers Solution for Bronx Race Tensions.” New York Amsterdam News, 26 April 1947.

[21] Biondi, Martha. To Stand and Fight: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Postwar New York City. Cambridge, Mass.; London: Harvard University Press, 2006.

[22] Dan Dodson, Common Council for American Unity, Box 37, Folder 337, Roll 19, Mayor’s Papers, New York City Municipal Archive.

[23] ”Puerto Rican Problems in New York City,” Box 276, Folder 3215, Roll 148, Mayor’s Papers, LaGuardia and Wagner Archives, Queens Community College.

[24] Pantoja, Antonia. Memoir of a Visionary: Antonia Pantoja. Houston, Tex.: Arte Publico Press, 2002.

[25] Summary Report of the Second Annual Conference on Civil Rights, NYC Central Labor Council, AFL-CIO, Saturday, 11 November 1961, OGPRUS, Centro Archive.

[26] “Intergroup Relations”. International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. 2008.

[27] Flyer, Bill of Rights Day, West Side Committee on Civil Rights, Box 284, Folder 55, Series III, Records of the Jewish Labor Committee, Wagner 25, Tamiment Library and Wagner Labor Archive, New York University.

[28] Committee on Civil Rights in East Manhattan, Edna Merson Chairman, to Mayor Wagner, 19 April 1954, Roll 54, Mayor’s Papers, New York City Municipal Archive; “How the tables are turning, how East Manhattan is achieving fair practices in restaurants,” Roll 54, New York City Municipal Archive.