Puerto Rican New Yorkers: Cigarmaker Organizing 1920s

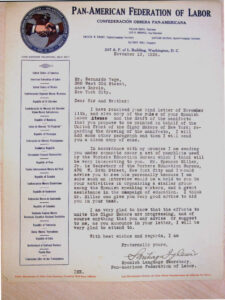

The 1919 cigar worker’s strike brought to the foreground the disaffection between workers and the main American Federation of Labor union that represented cigar workers, the CMIU. The workers behind the new Amalgamated Tobacco Workers of America (ATWA) had been among the insurgents behind the 1919 strike. Insurgents formally organized the ATWA in December of 1920, led by a faction of the more radical Italian, Jewish and Spanish speaking workers of the CMIU. The ATWA began publishing the bilingual ‘The Tobacco Worker’ in December 1920, and Puerto Rican labor leader Bernardo Vega became its secretary, a full-time organizer as well as co- editor of the new newspaper. At the founding convention of ATWA, delegate Ramirez celebrated the “spirit of the Spanish elements” and challenged the myth that they were against any form of organization. The ATWA committed to organizing the male and female machine operators in the tobacco trade, as these workers were displacing the traditional hand-rolled cigar manufacturers.[1] By 1926, the Amalgamated represented about 1200 workers in the City.[2]

Through the early 1920s, both the CMIU and Amalgamated continued organizing work as rivals despite the overall reduction in employment and union membership. Both unions received a boost from a 1922 wave of refugee migrants from Puerto Rico, the product of the defeat of a major strike there.[3] The Amalgamated concentrated rebels against the CMIU in four states, including Puerto Rico, with 4000 members.[4] The CMIU had advantages in this work, being linked with a national organization affiliated with the AFL. The CMIU continued to have Italian and Spanish-speaking sections in its battle against the Amalgamated. Bianco, a CMIU organizer who spoke Spanish and Italian noted that the Amalgamated had hired their own Italian and Spanish-speaking organizers and that the “Latin” cigarmakers violently opposed even discussing the CMIU with organizers: “[T]he Italian and Spanish speaking cigar makers had their minds poisoned with the activities and propaganda of our enemies.”[5]

Through the early 1920s, both the CMIU and Amalgamated continued organizing work as rivals despite the overall reduction in employment and union membership. Both unions received a boost from a 1922 wave of refugee migrants from Puerto Rico, the product of the defeat of a major strike there.[3] The Amalgamated concentrated rebels against the CMIU in four states, including Puerto Rico, with 4000 members.[4] The CMIU had advantages in this work, being linked with a national organization affiliated with the AFL. The CMIU continued to have Italian and Spanish-speaking sections in its battle against the Amalgamated. Bianco, a CMIU organizer who spoke Spanish and Italian noted that the Amalgamated had hired their own Italian and Spanish-speaking organizers and that the “Latin” cigarmakers violently opposed even discussing the CMIU with organizers: “[T]he Italian and Spanish speaking cigar makers had their minds poisoned with the activities and propaganda of our enemies.”[5]

In April 1922, employment in the industry improved somewhat. This facilitated a new organizing drive by the CMIU, which was encouraged by a meeting of 3000 workers and supported by the city’s major labor organizations.[6] The ATWA also continued its organizing work. In March 1925, the ATWA held a meeting of 500 members at the 84th St. Labor Temple, where leaders declared that the “old fighting spirit of the Amalgamated prevailed among those present.” The accusation that the ATWA was led by wild Bolsheviks intent on pushing for revolution was not readily apparent as the union focused on working conditions and achieving the 44-hour work week.[7] When M. Perez and Co. shut out 30 workers from its factory in New York and opened a plant in Pasaic (NJ), Amalgamated’s secretary called on Passaic workers (a militant center of industrial unions) for solidarity: …we are confident that you will help us in this fight for justice.”[8]

In 1925, workers in the tobacco unions began discussions for a reunification of their unions, leading to intense organizing meetings in the Puerto Rican and Latino community. Organizers estimated that they reached 2600 organized workers of which 10-12% were Latinos.[9] The Committee of Social and Economic Reconstruction of the TWA involved a city-wide effort but was especially intense among the Spanish-speaking workers. Spanish-speaking workers created the Comite de Reconstruccion Social y Economica, led mostly by CMIU leaders. They held mass meetings at the upper east side “Socialist Hall,” and rallies and workshop meetings among all cigar workers in the city. Puerto Ricans led the work for Spanish speakers, including Jose Vivaldi, Pedro San Miguel, Blas Oliveras, all of them active supporters of the Socialist Party in East Harlem and the Partido Socialista in Puerto Rico.[10]

Despite residing in Puerto Rico, Partido Socialista leader and full-time CMIU organizer Prudencio Rivera Martinez, who visited New York often, was the principal moral leader of the movement for reunification. He recognized that the Latino workers were the most radical element within the cigar worker’s movement. Rivera Martinez wrote a proposal to bring unity to cigar workers. The plan offered the Amalgamated locals complete autonomy if they joined the reformed CMIU umbrella. The plan was to hold an “international” mass meeting at the Labor Temple, an effort supported by the socialist New Leader, the Italian garment workers and other labor organizations.[11]

At a Comite de Reconstruction mass meeting at Socialist Hall E 84th, Prudencio Rivera Martinez promised the support of the city’s 700,000 unionized workers. CMIU Vice President Ornburn also spoke, with translation to Spanish, suggesting that both movements should meld.[17] A mass meeting of Puerto Ricans, Cubans and Italians at the Labor Temple presented speakers from the city’s labor movement and were addressed by Pedro San Miguel as the organizer of the Hispanic Committee.[18]

The challenges these leaders faced were daunting. Gender, ethnic, and political divisions within the unions were evident when workers at Consolidated Cigar (AKA Lovera) spontaneously went out on strike in July 1925. After the strike began, Spanish speakers and many Italians confronted the “Bohemian” workers, most of them women, who fought fiercely to return to work.[19] The union initiated a picket line and propaganda effort in the press in favor of the fired workers and worked to convince the Bohemians to support the reinstatement. The company agreed to the demands.[20]

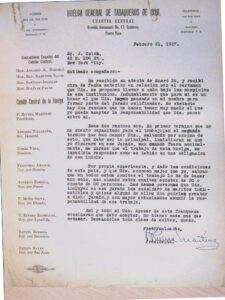

The organizing work continued between 1925-1927. Pedro San Miguel kept urging workers to seek the assistance of the committee in their local demands for better wages. The work of the Comite de Reconstruccion was intense. They held weekly meetings in order to “interersar directamente a la colonia de tabaqueros de la lengua española.” The meetings were bilingual and in the style of “tribuna libre”—an open jam session in which all could speak. At the meetings, the all-stars of the Hispanic CMIU leaders rotated, including Pedro San Miguel, Melhado, Aviles, Simmons, and Primitivo. At one of the meetings, San Miguel reminded workers of the need to unify the organizations, pointing to the militant fight that for 20 months the CMIU had been leading in workshop after workshop, with significant depletion of its funds. A subcommittee was created for agitation in “el barrio,” making it clear that workers could join either or both the CMIU and Amalgamated.[21]

A large August rally of 400 Hispanic cigar workers featured Puerto Rico’s Partido Socialista leaders Santiago Iglesias, Prudencio Rivera Martinez, and San Miguel. At the meeting, Rivera Martinez agreed with the familiar CMIU generalization that associated “latins” with revolutionary militant traditions and Saxons with conservative politics, but this time with a sympathetic tone of support. After hours of speeches, Santiago Iglesias urged all nonmembers to join the CMIU.[22] Another meeting with Latino cigar workers featured Santiago Iglesias. At this meeting, and despite the call for unity, Santiago Iglesias ranted against the pseudo-revolutionary promises of other groups and against communist groupings without mentioning the Amalgamated by name.[23] Every time Santiago Iglesias came through New York (which was frequently), major rallies were held, and after the speeches, the meetings turned into “Parlamento obrero.” The meetings and rallies helped keep workers aware of the different, sporadic strike efforts and facilitated mobilizing their support.[24]

A large August rally of 400 Hispanic cigar workers featured Puerto Rico’s Partido Socialista leaders Santiago Iglesias, Prudencio Rivera Martinez, and San Miguel. At the meeting, Rivera Martinez agreed with the familiar CMIU generalization that associated “latins” with revolutionary militant traditions and Saxons with conservative politics, but this time with a sympathetic tone of support. After hours of speeches, Santiago Iglesias urged all nonmembers to join the CMIU.[22] Another meeting with Latino cigar workers featured Santiago Iglesias. At this meeting, and despite the call for unity, Santiago Iglesias ranted against the pseudo-revolutionary promises of other groups and against communist groupings without mentioning the Amalgamated by name.[23] Every time Santiago Iglesias came through New York (which was frequently), major rallies were held, and after the speeches, the meetings turned into “Parlamento obrero.” The meetings and rallies helped keep workers aware of the different, sporadic strike efforts and facilitated mobilizing their support.[24]

In early 1927, a special meeting of leaders at the Labor Temple confirmed the final reunification of Latino tobacco workers with the merger of the Amalgamated led by Bernardo Vega as a new local chapter of the CMIU, reconfirming the leadership’s commitment to organizing new shops and support for the ongoing Philadelphia strike.[25] The leadership agreement was followed by a mass meeting and celebration at the Socialist Party Hall in East Harlem in April.[26]

Unity was only a path to continued organizing efforts. In October 1927, Latin cigarmakers and the Spanish Auxiliary Committee still called for workers to join the CMIU.[27] The following year, Pedro San Miguel reported how the Spanish and Latin people in many shops were afraid to join the union. He was working with Local 389 to do publicity work in Spanish and in many publications, including the bulletin of a Hispanic society that counted 2000 members, some of which were cigar makers.[28] The union, by now, had accepted the growing role of women and machines in the industry, but Latino leaders rarely mentioned organizing work among women.

By the decade’s end, most of the industry had left the city, mechanized, or become non-union. Hand-rolled cigarmaking as a whole declined. In a May 1929 letter to La Prensa, Armando Ruiz, head of one of the local CMIU locals, lamented the “crisis de los tabaqueros” and the inability of the movement to bring unity or improve conditions. He celebrated Pedro San Miguel’s efforts but blamed the indifference of many workers and declining attendance at union local meetings that could not meet quorum: “Tengamos el valor moral de declarar que marchamos hacia el caos, el desmembramiento y la ruina…”[29]

The text is copyrighted by the author, 2025.

Users may cite with attribution.

[1] The New York Times, 22 August 1926.

[2] Handbook of American Trade Unions. 1926, 144.

[3] La Prensa, 18 July 1922.

[4] Industrial Unionism in America. 1922. 289-295.

[5] The Cigar Makers Official Journal, 15 October 1922.

[6]The Cigar Makers Official Journal, 15 April 1922.

[7] La Prensa, 2 May 1925.

[8] Cigar makers call for solidarity, 16 April 1926, http://ciml.250x.com/archive/events/english/passaic_strike_1926/1926_pas…

[9] La Prensa, 6 June 1925.

[10]La Prensa, 2 May 1925.;

[11] La Prensa, 11 May 1925; La Prensa, 6 June 1925; La Prensa, 16 May 1925; La Prensa, 23 May 1925.

[17] La Prensa, 8 April 1925:

[18] La Prensa, 27 May 1925.

[19] La Prensa, 6 June 1925.

[20] La Prensa, 11 July 1925.

[21] La Prensa, 8 June 1925; 15 june 1925; 27 Julio 1925.

[22] La Prensa 6 August 1925.

[23] La Prensa, 19 September 1925.

[24] La Prensa, 16 March 1926; 22 March 1926.

[25] La Prensa. 29 March 1927.

[26] La Prensa. 21 April 1927.

[27] Cigar Makers Official Journal, October 1927

[28] Cigar Makers Official Journal, June 1928; May 1928; October 1927.

[29] La Prensa. 30 May 1929.