Puerto Rican New Yorkers: Labor Organizing in the 1930s

The Depression produced a torrent of working class organizing and protest in New York City. Both the Communist and Socialist Parties responded to the new desperate conditions, but the Communist Party connected most firmly with New York’s Puerto Rican and other Spanish-speaking communities. During the early 1930s the Communist Party organized its own militant industrial unions in competition with the unions affiliated with the American Federation of Labor or those associated with the Socialist Party. The Communist Party’s Trade Union Unity League (TUUL) brought together these new unions as part of its class confrontational line. The Communist Party also organized hundreds of unemployed councils, leagues, and workers committees, which could mobilize mass protests quickly. The Party dissolved the TUUL in 1935 when it changed to a policy of alliances with a less revolutionary rhetoric, even as its activists expanded their role in the growth of industrial unions and working-class movements during the late 1930s.

The Depression produced a torrent of working class organizing and protest in New York City. Both the Communist and Socialist Parties responded to the new desperate conditions, but the Communist Party connected most firmly with New York’s Puerto Rican and other Spanish-speaking communities. During the early 1930s the Communist Party organized its own militant industrial unions in competition with the unions affiliated with the American Federation of Labor or those associated with the Socialist Party. The Communist Party’s Trade Union Unity League (TUUL) brought together these new unions as part of its class confrontational line. The Communist Party also organized hundreds of unemployed councils, leagues, and workers committees, which could mobilize mass protests quickly. The Party dissolved the TUUL in 1935 when it changed to a policy of alliances with a less revolutionary rhetoric, even as its activists expanded their role in the growth of industrial unions and working-class movements during the late 1930s.

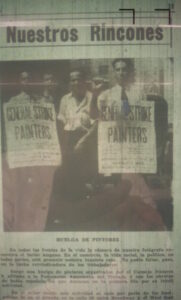

The TUUL had a Spanish-speaking local “bureau” in the Communist Party’s Casa Obrera de Habla Espanola in East Harlem and a national Spanish-speaking desk in downtown Manhattan.[1] In 1931, the Party’s Puerto Rican leader, Alberto Sanchez, followed the radicalized line of attacking “los lideres traidores del IWW,” accusing them of being agents of capitalism.[2] Nearly all the industries in which Puerto Ricans concentrated experienced the surge of labor and Left organizing. This included docks, ships, garment shops, metalwork plants, cafeterias, hotels, cigar shops, food processing plants, and so forth. In factory after factory, Puerto Rican workers (and a growing number of Spanish-speaking organizers) mobilized in defense of workers’ ability to earn a living. At the Eagle pencil factory on East 14th St., a Communist Party-led organizing effort included Spanish speakers. At this plant, half the workers were fired, reducing the force by hundreds. By December, all 1100 workers were on strike. Vida Obrera, newspaper of the Hispanic Section of the Communist Party, reported hearing Juan Pacheco, a Puerto Rican Communist Party sympathizer and member of the strike committee spoke to workers at their meetings at the nearby Labor Temple on the “franco optimismo de la huelga…ahora mismo salimos todos para el ‘picket line’”. Pacheco reported that the police “ha castigado a una companera que hacia el ‘picketing’…la companera se defendio valientemente, a pesar de que fue atacada de manera cobarde por dos policias.” At one point 150 Spanish-speaking workers were formed in two files holding out signs and singing political songs.[3]

Puerto Rican laundry workers, most of them women, also came into contact with Communist Party-led organizing for their own unions (the WTUL) during the early 1930s. TUUL organizers demanded $20 a week and seven hour days, inviting the Spanish-speaking workers to join the “Cleaners and Laundry Workers League.”[4] A WTUL led strike in 1934 received significant solidarity, including from Eleanor Roosevelt and her secret service agents.[5]

In 1930, Vida Obrera noted how many Spanish speakers had joined leftist unions as the TUUL expanded its drive to organize food, garment and other sectors. The Communist Party was astute about creating collectivities designed specifically to appeal to Latinos and Puerto Ricans. These relatively short lived efforts included the Asociacion Obrera Puertorriqueña, the Santiago Brooks (named after a Cuban Labor Leader), the Hispanic sections of the FWIU and the Needle Trades Workers Industrial union, the Hispanic section of the Anti-imperialist League of the Americas, The Liga Obrera Mexicana, the Centro Obrero de Habla Española de Brooklyn and Manhattan.[6]

The first years of the Depression led to severe reversals for garment workers and their unions. Massive layoffs meant unions lost most of their members, and wage cuts impoverished the workers. Sweatshop conditions returned to the city’s factories. Puerto Rican women (and some men) had entered the garment industry in the 1920s, but numbers grew in the partial recovery after 1932. The largest garment union was the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU), formed in 1900 and led by Jewish socialist immigrants, to unite many unions in the industry. ILGWU Local 22 became the largest local agglomerating the industry’s core: the dressmakers.[7]

During the early 1930s, Local 22 was in the process of recovery. The Depression reduced employment in garment dramatically, and in 1929 Local 22 had been reduced to 8000 members.[8] By 1933 The NRA and the slow recovery created conditions for a new wave of organizing.[9] The leaders of Local 22 made their first explicit appeal to Spanish-speaking workers in July 1931, inviting workers to a meeting with presentations in Spanish.[10] Local 22 was led by former Communist Party leader Charles (Sasha) Zimmerman, and it quickly developed a positive reputation for being a critical part of the lives of thousands of Puerto Rican and Latina garment workers. Local 22 was very successful after the 1933 general strike and organizing drive, and it recruited 2000 new Puerto Rican members, dramatically increasing its Hispanic membership.[11] The strike was a success and provided improvements: a 35-hour week, a 90-cent minimum, and the prohibition of overtime (to force employers to spread out the available work to the largest number of workers). Puerto Rican women joined a growing membership within ILGWU, which expanded to 200,000, including 3,000 Hispanics, 2,000 of which were in Local 22 and 700 in Local 91 (8%).[12] Local 22 had the largest concentration of Puerto Rican women in the industry. Spanish-speaking members comprised 6.5% of Local 22 membership in the mid-1930s.[13] At Hudson Dress in East Harlem, about 100 Spanish-speaking women with extremely low wages went on strike in October 1937, spurred by the organizers of Local 22. The workers sought to join the union and improve their wages.[14]

In 1934, various leftist factions allied and expelled the mobsters from Local 302 and took over its direction. The resulting unity process of cafeteria unions developed many Puerto Rican leaders. Juan Aviles was elected to the Executive Council in 1936, and Jose Garcia also worked as representative of the Local’s Spanish Workers Club in 1940.[13] After the merger, the union prepared for a general strike of food workers and held mass meetings of 600 led by the cafeteria workers local (FWIU). An organizing drive had gained 800 new members shared among all collaborating food unions. By November 1934 a large strike was called by Local 302 and with Local 110 of FWIU a joint strike committee was established. The AFL ordered Local 302 to end the strike, but Local 302 workers refused the order, holding out for the original demands of $35/week for countermen. By the end of 1936, the FPWIL merger with the AFL cafeteria locals was complete. Local 110 merged with Local 302, and Juan Aviles got elected to the Executive Committee of the local. They then affiliated with the CIO.

At the Horn and Hardart cafeterias, a company union provided minimal benefits to its 1000 workers, some of which had improved since the NRA. But wages were low, and black and female workers received even lower wages. When pressed with the threat of union organizing the company raised wages 5%. Another strike led by Local 302 at Horn and Hardart failed.[14] A strike at another cafeteria chain, Bickfords, lasted weeks but gave hope to Horn and Hardart workers. Local 302 efforts continued with another major organizing campaign in 1939.[15] Puerto Ricans and other Spanish-speaking workers had been central to the organizing drive in these cafeterias, including Childs. Local 42 leaders recalled “es para mi una felicidad poder expresar mi apreciacion profunda que siento por los compañeros hispanos de la local 42….Fueron ellos los que sentaros los nucleos en los diferentes establacimientos “Childs” sobre los cuales crecio y se desarollo la local.”[16] The prominent role of Spanish speakers led to having two Puerto Ricans in the Local’s leadership, boasting 3200 members, 400 of which were Hispanic.

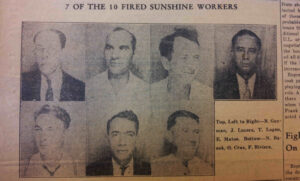

By 1940 Local 302 had grown to 10,000 members and included even more Puerto Rican workers than when it was reorganized. At Sunshine Biscuit Co. workers were fired for joining the union: John Lucero, a mechanic, Bartolo Guzman, a laborer, Felix an oven man, Otilio Cruz, a laborer, Eduardo Matos an oven man, Eddie Ortiz an oven man—all with 3 to 13 years of work at the plant. They received the solidarity of “hundreds of workers” who “ha[d] approached the discharged employees promising their full and wholehearted support.”[17] Eventually, the workers were reinstated, and wage increases won for the plant.[18] National Biscuit Company (later known as Nabisco, where dozens if not hundreds of Puerto Ricans worked since the late 1910s) was unionized in the mid-1930s. During the early years of the Depression, hours had been extended, and wages cut to $12/week for a 10-12 hour workday. In 1935, a major successful strike of its 3000 workers was declared.[19]

Hotel work was hard. Puerto Rican labor leader Armando Betances recalled making $15/week with no benefits during the 1930s for 48 hours of work. In order to earn a decent living he worked overtime for another 10 hours a day and got only a few hours of sleep. Even before he worked to bring the union, he organized the hotel workers to reject overtime pay unless it was a higher pay rate after a Depression pay cut, eventually forcing the hotel to pay time and a half at a rate of .45/hour in 1931. The 1934 hotel strike proved to be a critical moment in the organizing of hotels, a process that continued into the mid-1940s. As in many other industries, it was driven by a 25% drop in wages during the first years of the Depression. Cooks who started at $40 were now making $30.[20] A general strike of hotels was called in February 1934, and another in March 1936 when 2500 hotel workers in midtown joined building service workers, amounting to more than 7000 workers on strike.[21]

For a few years, the Communist Party had led and supported a parallel union movement. In December 1930, the Communist Party newspaper Vida Obrera called on Hispanics to join a city-wide rally at the Star Casino in Harlem to launch a general strike of garment workers.[15] The following year, in November, a mass meeting of garment workers was planned in Harlem by the Comite de Frente Unico de los Trabajadores de la Aguja, an effort by the Communist Party to organize its own garment unions.[16] Like all TUUL unions, the CP’s Needle Trades Industrial Union (of which the Dressmakers League was part), decided to merge with ILGWU Local 22 in 1934.[17]

The ILGWU did not establish Spanish-speaking locals (like the Yiddish and Italian locals created earlier in the 20th Century) but supported the organization of a Spanish-speaking section, which had offices and mass membership meetings in East Harlem. Saby Nehama, a Spanish-speaking Sephardic Jew, was named organizer of Local 22’s Spanish-speaking section in 1934.[18] Regular membership meetings of the Spanish section brought hundreds of women from the neighborhood to the Park Palace on 110th St and Fifth Ave. The regular meetings of the Spanish section lasted at least a couple of hours. One 1937 meeting in East Harlem brought Local 22 President Zimmerman, Antonini (leader of the ILGWU Italian Local) and Spain’s Ambassador in a rally against fascism that funds for the Spanish Red Cross during the Spanish Civil War.[19]

Local 22 had a strong educational program and a tradition of multicultural sociability and multilingual practices. Leaders designed programs that would help recruit workers of different ethnicities and immigrant origins when the union began to expand again in 1933. From the early 1930s, the union’s educational department offered English classes and social and cultural events that appealed to the Puerto Rican workers. The Local’s Spanish language department also organized its own events, which brought many non-Hispanic workers as well. In 1939, a dance at Audubon Hall in Harlem had sold nearly 2000 tickets.[20] As early as 1933, the Spanish section also ran a local Centro Educacional Espanol de los Dressmakers.[21] With an active educational division organized around the need for radical solidarity of a membership that included immigrants and US-born of different races, ethnicities, languages, and religions, Local 22 developed a strong ethic of unity and solidarity.

The culture of inclusion and solidarity within ILGWU locals had limits. As noted by Herberg “prejudice is regarded as a high crime in the union ethic, and no one will confess to it. But it is by no means absent from the shops, as all observers testify. Some years ago, Jewish workers were prone to accuse the “Italians” of “taking away” their work. [T]oday, both Jews and Italians tend to look askance at the newcomers for the same reason…the ethnic newcomers are made the object of very much the same stereotypes (“selfish,” “lazy,” “irresponsible,” “bad union people,” etc.) that were once applied to the now dominant groups of old-timers.[22]

Through the 1940s Black and Puerto Rican workers were concentrated in shops, making the lower price-lines “due to the reluctance of members of the better-established groups to facilitate the way to advancement for newcomers of the minority groups.” Green found that “some workers considered it a ‘social disgrace’ to sponsor a Negro or Puerto Rican worker in the trade. The sponsor lost standing in the shop.”[23]

In June 1937, the newly united and restructured Food and Hotel unions launched a massive organizing drive. An initial victory came with the organizing of the 52 restaurants and 3200 workers in the Childs restaurant chain, and many others followed. But the 1937 strike at Horn and Hardart ended in failure.[22] A January 1939 agreement with the members of the Hotel Association (63 hotels) set a standard for the entire industry of 41 cents/hour and a 48-hour week. The Hotel unions and their leaders helped form two of the Puerto Rican Community’s important activists. Gilberto Gerena Valentin and Armando Betances were both trained in these days of battle. One became a relatively apolitical union leader, while the other became perhaps the best-known radical Puerto Rican community leader through the 1970s.

Hotel organizer Armando Betances was born in Yauco in 1911 and migrated to New York after family troubles in 1927. He and his brother worked at the Plaza Hotel as silver polishers. In 1939, he was visited by a union agent at the hotel’s workers’ entrance and committed to the organizing effort. It took three years. He was fired once for getting workers to sign the cards required for an NLRB unionization vote, but his complaint to the Department of Labor got him reinstated. For Betances, Hotel union leader Jay Rubin was “el hombre que yo estaba esperando.” The hotel started improving conditions as soon as they learned the union drive was going on. Betances described his philosophy of organizing: “[I} was a rebel…I’ll fight for every little thing that is mine…and that’s the way I was all the time.”[23] Once the union arrived, pay was raised to $35/week for most workers, with many earning higher rates, twice the typical early Depression era wages. Betances became a full-time union organizer in 1954.

Community activist Victor Gerena Valentin first migrated to New York with his parents around 1919. His impoverished and crisis-ridden childhood was spent in New York and the island. His father was a Partido Socialista member who took him to marches, and later he was exposed to Albizu Campos’s Nationalism. Teased for being pale, blonde and blue-eyed (his grandparents were Spanish immigrants to Puerto Rico), he returned to join his siblings in New York in 1937 after finishing high school. His sister, a waitress, got him a dishwasher’s job at a restaurant and he started working as a volunteer organizer with Local 302 of the Cafeteria Workers Union. He recruited Spanish-speaking workers for the campaigns to organize the midtown cafeterias. When he started working in hotels (turning down a full-time organizer position with Local 302) he moved up quickly from dishwasher to much better pay cleaning rooms. He wrote of his pride at being one of the first to sign the union card to organize hotel workers under Local 6 of the Hotel Workers Union. He was elected union delegate in 1939 and started studying at nights at City College. His aptitude tests, as well as his skin color, got him on the exam to become an Air Force officer during WWII. Still, he purposefully botched the exam and ended up as radio operator and gunner on bombers. His contact with communist-led guerillas in the Philippines fighting the Japanese occupation helped reinforce his anti-imperialism. When he returned as a decorated veteran to his hotel job in New York he became a close collaborator of the Communist Party and the American Labor Party. By the late 1950s, Gerena Valentin would become one of the Puerto Rican community’s most important civil rights leaders.

Next: The Communist party and the Hispanic Popular Front

The text is copyrighted by the author, 2025.

Users may cite with attribution.

1] “Que debemos hacer por la Trade Union Unity League,” Voz Obrera, September 1930.

[2] “Los lideres traidores…,” Vida Obrera, 8 June 1931.

[3] Vida Obrera, 8 December 1930; Vida Obrera, 1 December 1930.

[4] Vida Obrera, 27 October 1930.

[5] Carson, Jennifer Lynn. “”It Takes Revolution and Evolution”: New York City’s Women Laundry Workers in the First Half of the Twentieth Century.” Ph.D. Dissertation. University of Toronto, 2007, 158.

[6] Vida Obrera, 1 December 1930.

[7] Leeder, Elaine J. The Gentle General: Rose Pesotta, Anarchist and Labor Organizer. Albany, N.Y: State University of New York Press, 1993, 34; Nadel, Stanley. “Reds Versus Pinks: A Civil War in the International Ladies Garment Workers Union.” New York History 66, no. 1 (1985): 48-72; Prickett, James Robert. “Communists and the Communist Issue in the American Labor Movement, 1920-1950.” Ph.D., University of California, Los Angeles, 1975, Chap. 2; Katz, Daniel. “Race, Gender, and Labor Education: ILGWU Locals 22 and 91, 1933-1937.” Labor’s Heritage 11, no. 1 (2000): 4-19; Katz, Daniel. All Together Different: Yiddish Socialists, Garment Workers, and the Labor Roots of Multiculturalism. New York: New York University Press, 2011, 99.

[8] Katz, Daniel. All Together Different: Yiddish Socialists, Garment Workers, and the Labor Roots of Multiculturalism. New York: New York University Press, 2011, 112

[9] Estimate of unemployment, Local 22 membership, Zimmerman Papers, ILGWU Collection, Kheel Center, Cornell University.

[10] Katz, Daniel. All Together Different: Yiddish Socialists, Garment Workers, and the Labor Roots of Multiculturalism. New York: New York University Press, 2011, 114.

[11] Asher, Robert Stephenson Charles. Labor Divided: Race and Ethnicity in United States Labor Struggles, 1835-1960. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990. Ortiz, Altagracia. “‘En La Aguja y El Pedal Eche La Hiel’: Puerto Rican Women in the Garment Industry of New York City, 1920-1980.” In Puerto Rican Women and Work: Bridges in Transnational Labor, edited by Ortiz Altagracia. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996; Laurentz, Robert. “Racial/Ethnic Conflict in the New York City Garment Industry, 1933-1980.” Ph.D. Dissertation, State University of New York at Binghamton, 1980.

[12] Katz, Daniel. All Together Different: Yiddish Socialists, Garment Workers, and the Labor Roots of Multiculturalism. New York: New York University Press, 2011, 120-4, 135.

[13] Herberg, Will. “The Old-Timers and the Newcomers.” Journal of Social Issues 9, no. 1 (1953): 12-19.

[14] La Voz, 20 October 1937.

[13] “Stalinists Cry Alien at Cafeteria Local 302 Man,” Socialist Appeal, 10 August 1940.

[14] “Dance for the Benefit of the Horn and Hardart Strikers of Local 302.”1937. New York Historical Society.

[15] “An Appeal to the Public! The Cafeteria Employees Union Local 302, appeals to you for support in their efforts to organize all non-union cafeterias,”1939, New York Historical Society.

[16] Verdad, 5 December 1939.

[17] The Food Worker, August 1934.

[18] The Food Worker, September 1934.

[19] “3,000 in NY biscuit strike,” New Militant, 19 January 1935.

[20] Herbart Solow, “The New York Hotel Strike,” The Nation, 28 February 1934; “LaGuardia Hears Hotel Strike Pleas, New York Times, 8 February 1934.

[21] “Walkout is Called at 17 More Hotels,” New York Times, 17 March 1936.

[15] Vida Obrera, 15 December 1930.

[16] Vida Obrera, 28 November 1931.

[17] To the workers of the Dressmakers Union Local 22, 20 December 1934, Zimmerman Papers, ILGWU Collection, Kheel Center, Cornell University.

[18] Katz, Daniel. All Together Different : Yiddish Socialists, Garment Workers, and the Labor Roots of Multiculturalism. New York: New York University Press, 2011,131-2; others;

[19] Local 22 Zimmerman 14, Zimmerman Papers, ILGWU Collection, Kheel Center, Cornell University.

[20] Local 22 Minutes, 1934-1972, ILGWU Collection, Kheel Center, Cornell University.

[21] Will Herberg to Antonio Reina, 18 December 1933, Zimmerman Papers, ILGWU Collection, Kheel Center, Cornell University.

[22] Herberg, Will. “The Old-Timers and the Newcomers.” Journal of Social Issues 9, no. 1 (1953): 12-19.

[23] Green, Nancy L. Ready-to-Wear and Ready-to-Work: A Century of Industry and Immigrants in Paris and New York. Durham N.C.: Duke University Press, 1997, 245

[20]Herbart Solow, “The New York Hotel Strike,” The Nation, 28 February 1934; “LaGuardia Hears Hotel Strike Pleas, New York Times, 8 February 1934.

[21] “Walkout is Called at 17 More Hotels,” New York Times, 17 March 1936.

[22] Labor Action, 30 December 1940.

[23] Interview with Armando Betances, Oral History Collection, Centro Archive; Interview with Armando Betances, Oral History Collection, The Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.