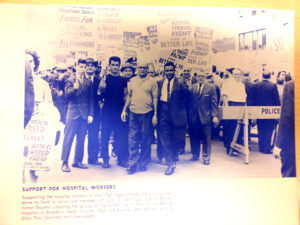

All of these efforts, including the union-led anti-racket fight had contributed to the emergence of over 400 Spanish speaking union leaders and hundreds of others shaped by leadership in the working class struggles of the preceding twenty years.

The presence of leaders in the unions was often centered in the various “Spanish-speaking” committees or clubs. During the 1950s the mid-level cadre of Puerto Rican labor leaders accumulated many lessons and experience within the unions, but also a long list of complaints against the union’s hesitation to support their work as Hispanics, to demand higher positions, and support the militant efforts for Puerto Rican workers. One of these leaders described their efforts and informal meetings as “semi-clandestine” because of their hesitation to work openly as an ethnic group.

Frank Perez and Mario Abreu were important players in this process, and their careers reflected both the support and training they had received from their unions but also the tremendous obstacles they witnessed in their efforts. These core Puerto Rican leaders were perceived as radicals by many leaders of the Central Labor Council, partially for asserting a strong ethnic identity that focused on the emerging consciousness of the needs of the growing Puerto Rican proletariat. These men had developed in the immediate post-war years a double consciousness about their role as Puerto Rican working-class activists. Frank Perez’s complaint represented well how these leaders felt about their work in the 1950s and early 1960s: “…siempre nos usaban como un objeto, como un instrumento, sin ser parte integral de la estructura y empezamos…clandestinamente…y nos reuníamos en diferentes clubes sociales. A veces hasta en la mismas casas de diferentes personas…”[40]Harry Van Arsdale was aware of this pressure and had handled it differently in the IBEW by encouraging Puerto Rican leaders to organize separately and in explicit support of Puerto Rican goals. His support would eventually lead to the incorporation of the Hispanic Labor Council as a formal advisory body to the CLC in 1969, although many Puerto Rican union activists would have said this move came a decade too late.

Consider the career of Eddie (Edward) Gonzalez. Gonzalez, a US born worker and WWII veteran, worked in shoe factories as a “union plant” organizing Puerto Rican workers in factory after factory for the shoe workers union. He then shifted to ILGWU organizing work and after more than ten years of this sort of work joined the employment office of the Migration Division as a field investigator. while working for the Migration Division during the mid-1950s he walked a difficult tight rope of supporting working class struggles while appearing neutral and “official.” This dance was familiar to Migration Division leaders including directors Senior and Monserrat). Gonzalez intersected with many others of his generation, educated working class Puerto Ricans who quietly or not so quietly linked the labor movement with the newly arrived workers. He networked with people like Fred Velez, also a WWII veteran and UAW Local 259 organizer who got the first Puerto Ricans into the Westchester high-pay auto parts factories.[41]

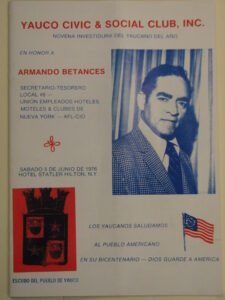

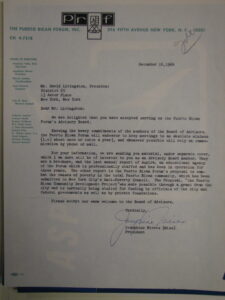

Paul Sanchez followed a similar path. Sanchez was part of the second-generation Puerto Rican leaders who came through from the factories, perhaps even as they earned college degrees. Sanchez was part of the group that networked with Eddie Gonzalez, Armando Betances, Frank Perez, Gerena Valentin and many others. Sanchez would become the first president of Central Labor Council’s Hispanic Labor Committee. Sanchez also served as Grand Marshal of the Puerto Rican parade in 1963, only one of many examples of the importance of unions and labor leaders to the Puerto Rican community in these years.

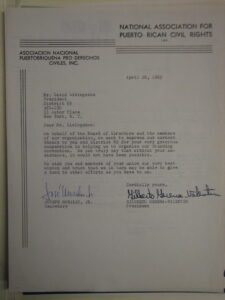

George Santiago is another example of this generation’s working class leaders. Santiago worked making lamps and joined IBEW Local 3. After serving in the Army in Korea, Santiago returned to factory and union work. Santiago joined the Mayor’s Committee Against Exploitation. He also was part of the group of labor leaders that created the National Association of Puerto Rican Civil Rights, the first formal Puerto Rican civil rights organization.[42]

Many leaders came also from the garment unions. Rafaela Balledares migrated as a child in 1929. After completing high school, she studied with a fellowship at a fashion school but never managed to develop a career in fashion design. Instead she worked in the garment factories starting in the late 1930s, often getting fired for complaining about conditions shared by the “cientos de mujeres puertorriquenas que trabajaban de sol a sol con limitados minutos para descansar.” Through the Woman Trade Union League, she was recruited as a union organizer for ILGWU Local 23 (Skirtmakers), training in labor studies. She organized her first ILGWU factory in 1943. At factory gates she did propaganda work for the union and would visit the women at home in the evenings to help them organize the shops.[43]

Balledares represented the ILGWU in many efforts during the 1950s. In the early 1950s she served as ILGWU representative to the Negro Labor Committee, led by Frank Crosswaith and A. Philip Randolph in Harlem. Here she joined some of the City’s most important labor leaders in an effort to help black workers organize. She was also active broadly across many sorts of organizations. She was involved in the organizing of the Fiesta Folklorica de Nueva York, a yearly festival celebrating Puerto Rican culture led by Gerena Valentin.[44]

Balledares was very involved in mobilizing Spanish speakers for the ILGWU-supported Liberal Party, the centrist vehicle for union politics that the ILGWU hierarchy created as a rival to the American Labor Party. Balladares went on to work with Puerto Rican antipoverty and civil rights organizations during the early 1960s while still working at a garment shop and after she retired in 1970 she became the organizer of the Fiestas de la Calle San Sebastian in Old San Juan, encouraged by Ricardo Alegria, Director of the island’s Instituo de Cultura Puertorriquena.[45]

Another important ILGWU leader who worked with Balladares, Frieda Montalvo, helped form The Agrupacion Femenina Latinoamericana, the more politically oriented group created out of the Agujas de Oro Latina garment workers club in ILGWU locals during the 1950s. Montalvo, also a depression-era migrant, was one of the young garment workers she organized through ILGWU Local 22. She became a lifelong political activist and public administrator in City Hall.[46]

Next: the Fight Against Exploitation

The text is copyrighted by the author, 2025.

Users may cite with attribution.

[1] Rohrlich, Ruby. The Puerto Ricans: Culture Change and Language Deviance. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1974, 173; Senior, Clarence. “The Puerto Ricans in New York: Progress Note.” International Migration Review 2, no. 2 (Spring 1968): 73.

[2] Communist Party, Puerto Rican Affairs Committee. Handbook on Puerto Rican Work. New York: Communist Party, Puerto Rican Affairs Committee, 1954. Liberacion offered a similar number in 1947: The NMU had 22,000 Hispanic members around 1947. Liberacion 4 January 1947.

[3] Misc., Box 1 Folder 1, Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees International Union, Collection Wagner 148, The Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.

[4] Executive Council Minutes, Box 189, Folder 7, New York City Central Labor Council Records, Wagner 049, The Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.

[5] Mayors Papers, Folder 988, 1951-3, Box 85, Folder 987-9, Roll 43, New York City Municipal Archive.

[6] Disperse notes 1940-1949, Tam#?, The Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives.

[7} Juan Rovira To Van Horn, 27 Sept 1941, Local 144, Series 2, Reel 18, Cigar Makers International Union Collection, Special Collections, University of Maryland.

[8] Misc,. Box 13, Folder 29, Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees International Union, Collection Wagner 148, Tamiment Library and Wagner Labor Archive, New York University.

[9] “12 Pickets Seized at Harvard Club,” The New York Times, 31 March 1948.

[10] “Investigan discriminación en industria hotelera NY.” El Diario, 30 Sept 1956.

[11] Senior, Clarence Ollson, and Isales Carmen. The Puerto Ricans of New York City. New York: New York Office, Employment and Migration Bureau, Puerto Rico Dept. of Labor, 1948, 51.

[12] Gray, Lois. “Case Study No. 7: The Puerto Rican Workers in New York.” In Joint International Seminar on Adoption of Rural and Foreign Workers to Industry, Paris: Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development, Manpower and Social Affairs Directorate, 1965.

[13] Stuart, Irving R. “A Study of Factors Associated with Inter-Group Conflict in the Ladies’ Garment Industry in New York City.” (Ph.D. Dissertation), New York University 1951, Table XIX.

[14] Herberg, Will. “The Old-Timers and the Newcomers.” Journal of Social Issues 9, no. 1 (1953): 12-19; Whalen, Carmen Teresa. “”The Day the Dresses Stopped”: Puerto Rican Women, the International Ladies Garment Workers’ Union, and the 1958 Dressmaker’s Strike.” In Memories and Migrations: Mapping Boricua and Chicana Histories, edited by Vicki Ruíz and John R. Chávez, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008.

[15] Stuart, Irving R. “A Study of Factors Associated with Inter-Group Conflict in the Ladies’ Garment Industry in New York City.” (Ph.D. Dissertation), New York University 1951, Table X.

[16] “The Old Timers;” Stuart, “A Study,” Table XI.

[17] Stuart, “A Study,” Table XII.

[18] The Advance, 15 June 1957.

[19] As cited in Carson, Jennifer Lynn. “”It Takes Revolution and Evolution”: New York City’s Women Laundry Workers in the First Half of the Twentieth Century.” Ph.D. Dissertation, 2007, 128, 227.

[20] The Advance, 15 February 1959; 1 July 1958; 15 June 1957.

[21] Leiter, Robert D. “The Fur Workers Union.” ILR Review 3, no. 2 (1950): 163-86.

[22] Interview with Eddie Gonzalez, Oral History Collection, Centro Archive.

[23] Stepan-Norris, Judith, and Maurice Zeitlin. Left Out: Reds and America’s Industrial Unions. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003, 216-17.

[24] International Union of Electrical Workers, Local 485, Box 3, Folder 1; Box 3, Folder 2, Collection 137, Tamiment Library and Wagner Labor Archive, New York University.

[25] Minutes of the Executive Committee, International Union of Electrical Workers, Local 485, 9 April 1958, Box 1 Folder 4, Collection 137, Tamiment Library and Wagner Labor Archive, New York University.

[26] Clifton Cameron to Paul Jennings, International Union of Electrical Workers, Local 485, no date, Box 2 Folder 35, Collection 137, Tamiment Library and Wagner Labor Archive, New York University; Biography of Angel Roman, Box 2, 3, Labor History Project, Centro Archive.

[27] Liberacion, 25 October 1947.

[29] Liberacion, 25 October 1947.

[30] Cecil Duran to Vito Marcantonio, June 1949, Vito Marcantonio Papers, Special Collections, New York Public Library.

[31] Puerto Rican Oral History Project, Brooklyn Historical Society.

[32] Puerto Rican Oral History Project, Brooklyn Historical Society.

[33] Puerto Rican Oral History Project, Brooklyn Historical Society.

[34] Ribes Tovar, Federico. Handbook of the Puerto Rican Community. El Libro Puertorriqueño de Nueva York. New York: El Libro Puertorriqueño, 1968, 302.

[35] Gray, Lois. “Case Study No. 7: The Puerto Rican Workers in New York.” In Joint International Seminar on Adoption of Rural and Foreign Workers to Industry. Paris: Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development, Manpower and Social Affairs Directorate, 1965.

[40] Interview with Frank Pérez, Oral History Collection, Centro Archive.

[41] Interview with Eddie Gonzalez, Oral History Collection, Centro Archive

[42] IBEW Local 3, “Those who have come our way,” no date, Box 2, Folder 3, Santiago Iglesias Educational Society Papers-IBEW Local 3 Archive.

[43] Clipping, New York Times, 1965?, Papers of the Communist Party, Series II, Box 231, Tamiment 132 Collection, Tamiment Library and Wagner Labor Archive, New York University.

[44] Gerena Valentín, Gilberto, and Carlos Rodríguez-Fraticelli. Gilberto Gerena Valentín: My Life as a Community Activist, Labor Organizer, and Progressive Politician in New York City. New York: Center for Puerto Rican Studies, 2013; Interview with Gilberto Gerena Valentin, Oral History Collection, Centro.

[45] “El alma de las fiestas,” El Nuevo Dia, 30 September 2011; “Many gains noted by Puerto Ricans.” The New York Times, 2 March 1964.

[46] “She embraced Puerto Rican heritage.” Orlando Sentinel, 20 December 2009; Interview with Eddie Gonzalez, Oral History Collection, Centro.