Puerto Rican New Yorkers: Socialist Politics 1920s

Between the late 1910s and 1920s, Puerto Rican workers and their Cuban, Spanish and other Hispanic peers built an impressive socialist movement that formed an integral part of larger support for the US Socialist Party and the Partido Socialista in Puerto Rico. In midtown and South Harlem, cigarmakers and other workers, often affiliated with the Socialist Party or anarchist clubs, formed the backbone of a male-dominant world based on the politics of class solidarity. Their activism was connected both to Puerto Rico as well as to Caribbean, Latin American and European immigrant workers and broader leftist organizing in the City. As within the cigar workers movement of the 1920s, Puerto Ricans were organized around loosely defined political tendencies. Independents, most likely anarchist-influenced leaders, who refused to align with any political party, supporters of the US Socialist Party and the island’s Partido Socialista (by far the dominant tendency), and a small group of radicalizing sectors who increasingly (especially after 1917) looked to the Communist (Worker’s) Party and the Soviet Union for inspiration.

Between the late 1910s and 1920s, Puerto Rican workers and their Cuban, Spanish and other Hispanic peers built an impressive socialist movement that formed an integral part of larger support for the US Socialist Party and the Partido Socialista in Puerto Rico. In midtown and South Harlem, cigarmakers and other workers, often affiliated with the Socialist Party or anarchist clubs, formed the backbone of a male-dominant world based on the politics of class solidarity. Their activism was connected both to Puerto Rico as well as to Caribbean, Latin American and European immigrant workers and broader leftist organizing in the City. As within the cigar workers movement of the 1920s, Puerto Ricans were organized around loosely defined political tendencies. Independents, most likely anarchist-influenced leaders, who refused to align with any political party, supporters of the US Socialist Party and the island’s Partido Socialista (by far the dominant tendency), and a small group of radicalizing sectors who increasingly (especially after 1917) looked to the Communist (Worker’s) Party and the Soviet Union for inspiration.

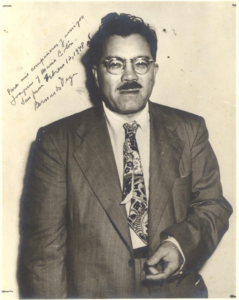

As Bernardo Vega (and his editor Cesar Andreu Iglesias) reported, working-class activism was as likely to connect Hispanics with non-Hispanic workers through unions, clubs and events. But by the mid-1920s, Puerto Ricans developed an especially militant affiliation with the US Socialist Party as an extension of their support for Puerto Rico’s Partido Socialista. Created by the island’s union movement as a vehicle of its own reform-minded candidates, the Partido Socialista was an affiliate of the US Socialist Party but followed its own directives and goals. Puerto Ricans in New York did not play a significant role in this relationship until the arrival of thousands of workers after 1917, as most migrants before 1919 (like famed Luisa Capetillo) were closer to the Spanish anarchists of Cultura Obrera, the El Corsario group and the Ferrer Center. Santiago Iglesias, one of the founders of the FLT and the Partido Socialista, had established an alliance with Socialist Party sectors in Tampa and New York even before he had developed his relationship with the AFL and Gompers.[1]

Bernardo Vega and other Puerto Rican tabaqueros were active in the Socialist Party even before they worked to organize Puerto Rican workers. Vega wrote for the Socialist Party daily, The New York Call which covered meetings and other events among Spanish-speaking workers. Pedro San Miguel and A. Torres organized a meeting in support of a socialist candidate London in 1916: “Porto Ricans interested in the fight of their countrymen to escape enslavement on the plantations of the island through disfranchisement and Cossack rule will meet Sunday.”[2]

Puerto Rican migrants entered the Socialist Party during a period of recovery from the harsh Wilsonian repression of socialist and anti-war activism, when the implications of the 1917 Russian revolution were still being hashed throughout the working-class movement. During the early 1920s, Puerto Ricans entered a Socialist Party that was recovering but one that had reaffirmed its electoral, social-democratic path.[3] Reenergizing its electoral participation, especially through Norman Thomas’ candidacies and the creation of the League for Industrial Democracy, as well as new alliances with a rising tide of African-American socialists including Randolph, focused its resurgence in New York City while many areas in the Midwest and other states were disorganized and lost. Despite the local recovery of the Socialist Party, it would no longer be the singular leader of the working-class movement in the US.

One of the Socialist Party’s activism centers was the multi-ethnic working-class communities of East Harlem. East Harlem was one of New York’s centers of Socialist organizing in the 1900s and 1910s. The Socialist Party had strong working-class and middle-class support among the Russian Jews, Germans, Italians, and Finns of the area.[4] East Harlem housed many of the Socialist Party’s meeting place,s including a major headquarters and the Finnish Socialist Labor Hall on 125th St. [5] In November 1917, a rally for Socialist Party and union leader Morris Hillquit was organized in the area with an expected attendance of 15,000.[6]

The first Spanish-speaking section of the Socialist Party was formed in 1912, with over 100 cigar workers attending the organizing meeting.[7] A few years later, a similar number, now mostly Puerto Ricans, joined Bernardo Vega in a support rally for Puerto Rico’s striking sugar cane workers.[8] Efforts like these would become a permanent part of the community’s life with fundraisers at work, particularly in the cigar shops, and as part of community dances that sent money to striking workers on the island.[9] Puerto Rican support and participation for the Socialist Party continued to grow throughout the 1920s, with many meetings and rallies at the Harlem Socialist Hall (62 East 106th St) organized by the Seccion Socialista Hispana.[10]

Cigar workers and others connected to the Socialist Party and the Spanish-speaking section of the Socialist Party served as a bridge, placing US Socialist politics also at the center of the Puerto Rican community. Puerto Ricans mobilized in support of Norman Thomas’ campaign out of this branch and he addressed them in meetings of the Spanish language section.[11]

The Socialist Party’s extensive resources were an important source of support for Puerto Rican working-class leaders at many levels. The Rand School trained many Puerto Rican leaders and activists, including Luis Munoz Marin, Jesus Colon, and Bernardo Vega.[12] The school even operated in the East Harlem Headquarters of the Socialist party at the Harlem Terrace.[13]

Puerto Rico’s Partido Socialista, founded in 1915, and rooted in the class politics of the Federacoin Libre de Trabajadores, the alliances of skilled artisans and town proletarians, had shown its power in the elections of 1918 and quickly became a significant political force. An early participant in these politics, a Partido Socialista member in Puerto Rico who even served as a delegate to a Socialist Party convention in St. Louis, Luis Muñoz Marin shared street corner rallies, public lectures and harangues with Puerto Rican workers in Harlem. Munoz Marin joined the Socialist Party in 1919 and immersed himself in New York’s multi-ethnic socialist world. On his initial return to the island in 1920, he stood to the left of Santiago Iglesias, his mentor, and many other national leaders of the Partido Socialista, rejecting political alliances with bourgeois parties.[14]

Munoz Marin, like most Partido Socialista leaders, were convinced that the future of social reform in Puerto Rico was tied to the future of socialism in the US.[15] Like most Puerto Rican socialists of the 1920s, Munoz Marin was not a radical revolutionary but believed in gradual, pragmatic and electoral change accompanied by militant class-based activism.[16] In 1920, when visiting the island, Munoz Marin became Santiago Iglesias’s secretary and joined him on his local campaigns in support of striking workers throughout the island, where he became a “fiery speaker,” as eclectic as Puerto Rican island socialism.[17] Despite this, his socialism, like that of the Partido Socialista, was tamer. Munoz Marin’s education as a socialist is described by his biographers as Fabian, consistent with democratic, evolutionary socialism, which had few maps on how to achieve socialism other than through electoral means and had much in common with radical liberalism.[18]

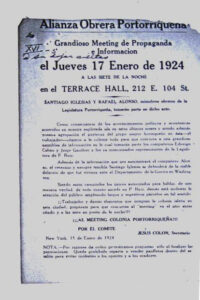

By the mid-1920s, Puerto Rican working class organizing in New York City had matured into its own organization. The Alianza Obrera emerged as a supporter of the Socialist Party and Partido Socialista politics–a transnational bridge connecting working class needs and organizing in both places. Puerto Rico’s bitter political and class fights of the 1910s and 1920s found echo in New York. The Alianza Obrera Puertorriquena was founded on Labor Day in 1923 at Terrace Hall by the emerging leaders of the socialist and cigar workers movements, including Jesus Colon, Bernardo Vega, Eloy Franquis, Luis Munoz Marin, Prudencio Rivera Martinez, Lupericio Arroyo, and Eduvigis Caban and others.[19] By some counts, the crowd was between 600 and 1000 people, but the large turnout made it clear to La Prensa that “la Alianza manda en el lado este de la cuidad.” At the Alianza’s founding rally, diverse political positions were presented.

The Alianza, was created in a contest with other more conservative sectors in the Puerto Rican community [20] served as the link between Island and mainland socialist and working class politics.[21] The Alianza could draw hundreds of workers to its meetings and rallies, especially when Munoz Marin, Santiago Iglesias, or US Socialist leaders led the billing.[22] Including the most important political meetings of the 1920s.[23] The Alianza sponsored rallies including one celebrating—in the tradition of the AFL—labor day. Jesus Colon described the speeches to over a thousand workers assembled in East Harlem in an editorial for Caribe, spoken in support of the worker’s movement on the island. Luis Munoz Marin, Lupericio Arroyo, Prudencio Rivera, Santos Bermudez and Pedro Esteve debated working-class politics.[24] The Alianza received an official endorsement of its links to Puerto Rico’s socialist and labor movement from the 1924 convention in Arecibo, rejecting the “buscones” of the middle-class civic associations that shared the growing south Harlem settlement.[25]

Alianza Obrera Puertorriqueña 1924

Most Puerto Ricans continued to support the Socialist Party throughout the late 1920s but the1929 depression began the near complete reconfiguration of politics in Puerto Rico and New York. The Partido Socialista’s electoral alliance with the Partido Republicano in 1932, signaled the break of most New York workers and leaders with the Partido Socialista. It also brought a slow transition between 1929 and 1934 of the community’s leaders from the orbit of the Socialist Party to the Communist Party.

The text is copyrighted by the author, 2025.

Users may cite with attribution.

[1] Erman, Sam. Almost Citizens: Puerto Rico, the U.S. Constitution, and Empire. Cambridge, United Kingdom: New York, NY, USA, 2019, Chap 3; Http://newyorkhistoryblog.org/2013/04/03/torcedores-gothams-hispanic-cigar-rollers-at-work; Ruíz, Vicki; Sánchez Korrol, Virginia. Latinas in the United States: A Historical Encyclopedia. Indiana University Press, 2006, 585; Hewitt, Nancy A. Southern Discomfort: Women’s Activism in Tampa, Florida, 1880s-1920s. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001, 115, 126-127; Martinelli, Phylis Cancilla, Ana M. Varela-Lago, and Hidden out in the Open: Spanish Migration to the United States (1875-1930). Louisville, Colorado: University Press of Colorado, 2018, 115-116.

[2] Socialist Call, 18 October 1916.

[3] Dubofsky, Melvyn. “Success and Failure of Socialism in New York City, 1900-1918: A Case Study.” Labor History 9, no. 3 (Fall 1968): 361-75.

[4] Leinenweber, Charles. “The Class and Ethics Bases of New York City Socialism, 1904-1915.” Labor History 22, no. 1 (Winter 1981): 31-56.

[5] Socialist Call, 1917.

[6] Socialist Call, 3 November 1917.

[7] Ruíz, Vicki and Sánchez Korrol Virginia. Latinas in the United States: A Historical Encyclopedia. Indiana University Press, 2006, 585.

[8] Passim, Jesus Colon Collection, Centro Archive.

[9] La Prensa, 22 March 1927.

[10] Partido Socialista at Harlem Socialist Hall, Box 21, Jesus Colon Papers, Centro Archive.

[11] Morris E., Campaign Manager, to Jesus Colón, 11 October 1928, Box 2, Jesus Colon Collection, Centro Archive; Justicia, 11 June 1923.

[12] Reel 50, Delo 717, Records of the Communist Party USA in the COMINTERN Archive, Tamiment Library and Wagner Archive, New York University; Rosario Natal, Carmelo. La Juventud de Luis Munoz Marin: Vida y Pensamiento, 1898-1932. Rio Piedras, P.R.: Editorial Edil, 1989.

[13] Katz, Daniel. All Together Different: Yiddish Socialists, Garment Workers, and the Labor Roots of Multiculturalism. New York: New York University Press, 2011, 217.

[14] Rosario Natal, Carmelo. La Juventud de Luis Munoz Marin: Vida y Pensamiento, 1898-1932. Rio Piedras, P.R.: Editorial Edil, 1989.

[15] Ayala, César J. Bernabe Rafael. Puerto Rico in the American Century: A History since 1898. University of North Carolina Press, 2007, 98.

[16] Rosario Natal.

[17] Antrop González, Rene. “El Pensamiento Socialista De Luis Muñoz Marin.” Horizontes 40, no. 79 (1998): 195-202.

[18] Rosario Natal.

[19] El Caribe, 1923; La Prensa, 4 September 1923.

[20] See Alianza Obrera Portoriquena, 7 January 1923 ; Secretario to Camarada, Box 15, Jesus Colon Collection, Centro Archive.

[21] Records of the FBI on Luis Munoz Marin, HQ-100-5745, Vol. 03. P. 9; La Prensa, 11 September 1923.

[22] La Prensa, 12 December 1923.

[23] El Caribe, 1 September 1923.

[24] El Caribe, 8 September 1923.

[25] “Resolucion aprobada…,” Box 15, Jesus Colon Collection, Centro Archive.