Puerto Rican New Yorkers: The Depression

After the stock market crash of 1929, unemployment in New York City expanded dramatically. In April 1930, the number of unemployed reached 234,000 for the whole city and had grown to 540,000 by December. Two months later there were 609,000 unemployed men in Manhattan, Brooklyn and the Bronx. By the end of 1930 the citywide unemployment rate was 18%. Manufacturing, a sector on which the majority of Puerto Ricans relied on for employment, had declined by 20%,[1] Conditions worsened by 1932. A modest recovery over the following two years (1933-1935) increased employment by a whopping 35% but did not restore wages and hours to pre-depression levels. Wages and employment opportunities declined dramatically for many, if not most, Puerto Rican workers in New York City during these years. Significant recovery arrived only in the late 1930s, and only then through the combined actions of the public sector and the demands made by working class movements and organizations.

After the stock market crash of 1929, unemployment in New York City expanded dramatically. In April 1930, the number of unemployed reached 234,000 for the whole city and had grown to 540,000 by December. Two months later there were 609,000 unemployed men in Manhattan, Brooklyn and the Bronx. By the end of 1930 the citywide unemployment rate was 18%. Manufacturing, a sector on which the majority of Puerto Ricans relied on for employment, had declined by 20%,[1] Conditions worsened by 1932. A modest recovery over the following two years (1933-1935) increased employment by a whopping 35% but did not restore wages and hours to pre-depression levels. Wages and employment opportunities declined dramatically for many, if not most, Puerto Rican workers in New York City during these years. Significant recovery arrived only in the late 1930s, and only then through the combined actions of the public sector and the demands made by working class movements and organizations.

Puerto Rican workers recalled the difficult conditions in interviews and testionies. Nick Perez remembered “starving” and his cousin “selling apples in streets,” saved by donations from sister Carmelita’s settlement home in Williamsburg. Pedro Crescent remembers joining a bread line during the Depression. When he found work earnings were only $8-10/week, less than half of the typical late 1920s wages.[2] Another Puerto Rican remembered the food offered in soup kitchens: “sancocho podrido con pan viejo y duro que nos dan despues de angustiosa espera en las fila de hambrientos.”[3]

Most workers saw their wages cut and their work hours extended. This meant dire conditions for food and housing, including an epidemic of evictions. Wages, even after important concessions from employers in the mid-1930s, remained low and often lower than during the 1920s. One worker reported irregular work and hours of one dollar a day. At the GEM/ American Safety Razor factory, where chain hiring had increased the number of Puerto Rican workers during the 1920s, one Puerto Rican worker reported firings and reduced wages in October 1930 down to $17 a week.[4] At the National Container factory in Long Island City, a Latino worker reported “no puede usted imaginarse cual es la situacion de los obreros de esta fabrica.” All workers at this site faced reduced wages and a 50-hour week, with pay that ranged from $12 to $16. Workers were in shock over repeated10% wage reductions over six months.[5] Hotels had similar cuts in wages and increased hours. At the New Yorker Hotel where many Spanish speakers worked, a Hispanic worker starting as a dishwasher could earn only $15/week, about a 25% or reduction from pre-depression wages..[6]

Puerto Rican women entered the work force in increasing numbers during the 1930s, working in garment shops, laundries and food factories. Laundries offered the lowest pay at $12 to $14 weekly, and conditions were very poor. Thirteen-hour workdays, low wages for men, and even lower wages for women were common in the early 1930s.[7] Minerva migrated just as the Depression was about to start. She preferred working in the laundries to garment work because the work was steadier. During the Depression she made only $12-14/week for 12-hour days that included Saturday work. She had steady work during the Depression as was glad she didn’t have to rely on welfare. When she got her own apartment in 1938, she considered it an improvement. As Jews were moving out, Puerto Ricans gained access to better apartments.[8]

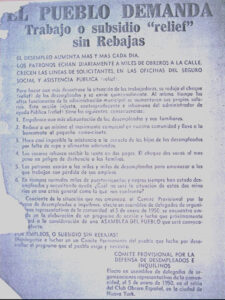

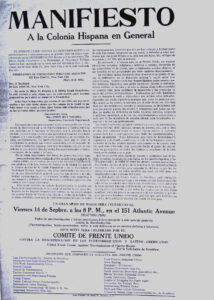

As income from wages declined, Puerto Rican families sought the same sorts of assistance available to other New Yorkers with citizenship rights—but cultural, racial and political obstacles were often in the way, heightened by the new institutional frameworks created by public and para-public agencies and the prejudices and preferences of those who created or administered these programs. One of the persistent themes of the 1930s was that Puerto Ricans had to fight for their share of the emerging relief and public employment benefits.

As income from wages declined, Puerto Rican families sought the same sorts of assistance available to other New Yorkers with citizenship rights—but cultural, racial and political obstacles were often in the way, heightened by the new institutional frameworks created by public and para-public agencies and the prejudices and preferences of those who created or administered these programs. One of the persistent themes of the 1930s was that Puerto Ricans had to fight for their share of the emerging relief and public employment benefits.

Despite a large scale presence in New York for decades, Spanish speakers still faced obstacles in procuring services as their right to inclusion in public releif efforts was questioned formally and informally. Housing, health and recreation posed problems to the community, especially if they spoke no English. Moises Ledesma noted in 1936 the limited services for Spanish speakers and few Spanish-speaking staff in social agencies serving the communities where Puerto Ricans and other Latinos predominated.[9] But pressure from allies and the community itself helped turn the attention of social workers and other service providers towards the Puerto Rican community, an attention that was often focused on locations with large numbers of Puerto Ricans and other Spanish-speakers.

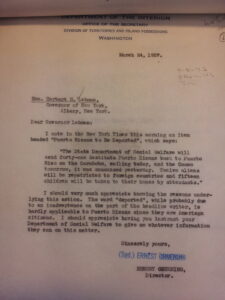

The Depression also affected migration from the island. On one hand, it reduced the total flow of migrants by marking a significant net return of people to the island. On the other hand, it also led to the arrival of poorer, more desperate migrants with few work skills, no English and little education. One 1937 study that focused on 23 of the poorest families in Brooklyn (labeled by the authors as “the lowest class”), reported very modest, poor households. Nearly half of these families had arrived since the Depression began. The study partially confirmed fears that a few hundred recent immigrant families ended up on relief upon arrival in New York City, unable to find work.[10] A “repatriation” program, organized by the New York State Board of Charities and the Red Cross, encouraged and paid for a few dozen Puerto Rican families to return to the island starting in 1931. This was a coordinated effort, with Puerto Rico’s Governor Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. and urged islanders not to migrate to New York as it was likely they would end up in a more precarious position.[11] The agencies established a policy of paying for travel costs for migrants with no source of income willing to return to the island, and 60% of their cases accepted the return passage.[12] Forty-one people were returned by State Welfare in 1937.[13] Knowledge of the “repatriation” program created an uproar in the community’s organizations and colonial administrators until it became clear that it was based on voluntary participation and was part of similar efforts for migrants from other parts of the US.

Social workers, focused on the poorest and least adjusted, found, predictably, that the initial explanation for the extreme poverty of Depression era migrants was their lack of English skills, which were now doubly important for survival in managing public agencies, public employment and patronage/service networks.[14] Brooklyn social agencies reported being “swamped” by requests for aid and relief from Puerto Ricans in 1930.[15] By the end of the decade there were 2,380 Puerto Rican relief cases, still a modest number considering the number of Puerto Rican households. This figure was thought to be large by administrators, even though it represented only 5% of Puerto Rican households. Puerto Rican and New York agencies collaborated in researching the needs of these families. They reported that 60% of the poorest families offered paid transport to Puerto Rico took the offer, with continuity of caseworkers transferred to Puerto Rico agencies.[16]

Relief payments were critical to those who were already vulnerable. An older woman from San Juan lived alone and worked in a large factory in Hoboken but lost her job. She then alternated periods of illness with domestic and janitorial work, but had to go on relief for years in the late 1930s. Her very poor health and lack of English kept her isolated. In her ill health she could barely get up and down the stairs. Her only source of strength came from her participation in both the Catholic Church and the Communist Party.[17] For others, relief payments covered long stretches of unemployment despite strong work histories and skills. A schoolteacher from Villalba who grew up cutting cane, picking coffee, and working in tobacco factories on the island had felt “forced to emigrate.” His family had owned a modest coffee farm, but it was lost to a merchant. When he fought against this politically connected prestamista he was fired from the school. In New York, in 1926, he began work as a carpenter and metal worker at the United Wire Works in upper Harlem, making a good wage of $25/week. At the wire works they had an “independent workers union called the Excelsior Workers which really tried to defend our working conditions.” But he was laid off in the depths of the Depression in 1933. He found work until 1939 as a carpenter with the Civil Works Administration (a federal jobs program) but was fired and had to go on relief. “I must work and can’t stand being idle…That I would like to see in a real building program, so that I, as a carpenter, could get steady work and feel that I’m building something.”[18]

Next: Responses to the Depression

The text is copyrighted by the author, 2025.

Users may cite with attribution.

[1]Lonigan, Edna. Unemployment in New York City; an Estimate of the Number Unemployed in December, 1930, and the Sources of Information on the Extent of Unemployment in New York City. New York: Research Bureau, Welfare Council of New York City, 1931.

[2]Interview, Puerto Rican Oral History Project, Brooklyn Historical Society.

[3]Vida Obrera, 27 April 1931.

[4]Vida Obrera, 27 October 1930.

[5]Vida Obrera, 2 February 1931.

[6]Vida Obrera, 22 December 1930.

[7]Vida Obrera, 22 September 1930.

[8]Interview with Minerva Rios, El Barrio Popular Project, Oral History Collection, Centro Archive https://centropr.hunter.cuny.edu/digitalarchive/index.php/Detail/objects/4351

[9]Ledesma, Moises M. “Sociological Background of the Puerto Ricans.” Thesis, Columbia University, 1936.

[10]Rodriguez, Manuel. “A Study of the Puerto Ricans in New York City and Their Difficulties in Adjusting to Cosmopolitan Life.” Thesis. Columbia University, 1937; “A Refugee Problem in New York: Porto Ricans Flee from Destitution into New Troubles.” Better Times, 7 April 1930, 17-19; Shulman, Harry Manuel. Slums of New York. New York: A. & C. Boni, 1938, 339.

[11]McGreevey, Robert. Borderline Citizens: The United States, Puerto Rico, and the Politics of Colonial Migration. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2018.

[12]Hall, Frances Adkins. “The Problem of the Migration of Indigent Puerto Ricans to and from New York City.” Puerto Rico Health Bulletin, no. 3 (Dec 1939): 496-504.

[13] The New York Times, 24 March 1937.

[14] Another study of an East Harlem “slum” block found 20% of families spoke no English. (Shulman, Slums of New York.)

[15]The New York Times, 22 May 1930; 2 April 1930, Thos. J. Rile, Brooklyn Bureau of Charities, to William Hodson, New York Welfare Council, Box 1138, File 9-8-116, Classified file, 1907-1951, Record Group 126, Office of Territories. United States National Archive.

[16]Hall, Frances Adkins. “The Problem of the Migration of Indigent Puerto Ricans to and from New York City.” Puerto Rico Health Bulletin, no. 3 (Dec 1939): 496-504.

[17]Case history no. 1 1939, Spanish Book section, WPA Records, New York Municipal Archive.

[18]Case history no 2. 1939, Spanish Book section, WPA Records, New York Municipal Archive.