Puerto Rican New Yorkers: The Fight Against Exploitation

Initial Efforts: The Migration Division

The Migration Division (the office of Puerto Rico’s Labor Department in New York) was involved in promoting the organization of workers and in linking Puerto Ricans to “legitimate” unions. Among the different interventions the MD carried out, it sent its own investigators to visit plants. Then, it followed up with union, city, or federal agencies, using the contacts of MD staff and directors in the union movement to encourage organizing drives or decertification votes against corrupt locals. The MD balanced its need to be discrete with its intimate knowledge of worker experiences and complaints. It often chose a quiet path to address worker demands because of the sensitive politics of Puerto Rican politics in New York and the official status of the office. In the mid-1950s, the MD intensified its role as a facilitator and instigator of worker’s demands. During the early 1950s, it was involved in minor crisis interventions and large-scale facilitation among the major AFL and CIO unions. Still, the MD was not ready to handle the deluge of protests that its own work had helped generate after the mid-1950s.

The signs of the exploitation of this large minority of Puerto Rican workers have been visible to community leaders since at least 1950. Federal Labor Department officials, including Arthur White, Labor Department Regional Director for New York, noted in their bulletin that “many Puerto Ricans working in New York City may not be receiving the minimum wage of 75 cents and are not being paid time and one-half for overtime.”[3] Practically any article written about Puerto Rican migrants in the post-war years at last mentioned the exploitative conditions that many found in factories and other workplaces.

Escalating complaints in 1955 involved the Migration Division further. The revolt of workers at Jay Kay Metal Specialties Corp of Long Island City in Queens provided one example of the Migration Division’s involvement with workers. Other complaints received by the Migration Division increased after 1955 once workers became bolder and learned on how to call for support from various actors, including the MD. By the mid-1950s, the work of the Migration Division was so visible that Communist Party activist Jesus Colon, who still led the party’s Spanish-speaking section, commended the Migration Division for its approach to labor organizing in the mid-1950s.[4]

The Association of Catholic Trade Unionists

The Association of Catholic Trade Unionists played a major role in inciting and channeling Puerto Rican complaints and mobilization. The ACTU was a Catholic organization of labor leaders and rank-and-file workers that had fought against the Communist Party’s influence in unions and mobster control of the docks. The remnants of the ACTU in New York—unionists, priests, professors, lawyers, and students—had been providing labor education workshops with a focus on countering the influence of the Communist Party. But in 1953, they began organizing English language and labor leadership classes for Puerto Ricans and other Latinos through the parishes of East Harlem and the Bronx. The young ACTU activists got to know the factories from which they were recruiting workers and the island where most of these workers came.[5] The men who participated in the courses began to report on sweatshop conditions of unions that took their dues and did nothing in return. Workers in the program quickly began to contest their conditions at work. One of the participants was elected shop steward and filed a grievance, which went nowhere. The result was that “He called all the workers out of the shop and paraded them from Brooklyn to the rather plush offices of the union headquarters in New York City. He had “rights” and he would enforce them, much to the displeasure of his very embarrassed union leaders. This was the first “strike” a certain very mature union had in a very long time in New York.”[6]

Through these efforts, ACTU leaders learned of Puerto Rican workers’ many complaints and demands and began to channel their complaints and provide legal advice. Their goal was to help workers in plants with no union to petition the NLRB for a vote, or in the case of racket unions, organize de-certification votes. ACTU quickly networked with the Migration Division, the Spanish language press, and industrial unions (especially the IUE and District 65) to help workers lead strikes, receive legal advice, petition the NLRB, and organize support for picket lines. ACTU militants held dozens of meetings, carried out interviews, gathered meticulous data, supported pickets, and held meetings from plant to plant.

The Rebellion of the “Exploited” Workers

During 1956 and early 1957, the fight against racket unions exploded on the New York and national scene. At the national level, federal authorities led the effort, in part as part of a pro-business group’s effort to weaken militant unionism. However, in New York, this movement initially connected disparate interests, bringing together groups that had made efforts to improve the status of Puerto Rican workers but had not yet coalesced. By the summer of 1957, worker insurgency and interventions from multiple actors had exploded into a dizzying daily narrative. At the factory level, the movement had no central leadership and involved thousands of workers and dozens of leaders and institutional actors. This was just the start. Puerto Rican workers mobilized pickets, met with journalists and lawyers, migration division staff, filed NLRB petitions, scuffled with police and managed the tremendous workplace demands of organizing, often clandestinely, petitions, protests, strike plans and rebellions aimed at both the bosses and the union. The list of actions is impressive, as well as the commitment by both workers and their allies to rid themselves of a sinister threat that not only diminished the wages of the “exploited” workers but threatened the image and politics of the entire labor movement.

The first major intervention by the ACTU developed in early October 1956 at leather products factories Rudees and Morgan’s. Initially, both efforts failed as employers were able to break the resolve of many of the workers, even after strikes and pickets were formed. Before the October strike and NLRB decertification filing, workers had organized the “Workers Organizing Committee.” The WOC, led by Juan Hernandez and others, publicly challenged AFL-CIO leadership in September to support their efforts and their insurgency against those who “prey on Puerto Rican workers.” They explained that they “Want to belong to the American labor movement but could never remain a party to this city-wide exploitation of Puerto Rican workers by Lustigman…Help us and other workers who are in the clutches…we are in great fear of our lives, and our bosses who are now instituting speed ups and are firing some of our workers.”[7] That September the NLRB recognized the WOC as a legal union.[8]

By late 1956, ACTU was helping coordinate worker revolts in a few dozen factories and had embarked in a major campaign against the corrupt unions that were part of the AFL-CIO. ACTU had been using its networks of workers and activists to investigate the IJWU since January 1956 when workers at one plant visited Perez, coordinator for the PR Labor Committee to complain about their local. In March, Puerto Rican women from Lido Toys complained of bias with a formal complaint to the State Commission against Discrimination (SCAD) against Local 222. A cascade of revolts against Jewelry Worker’s Local 222 followed. Workers at Knomark Manufacturing, Emenee Industries, Deliza and Ester Co., Fulton Manufacturing, Lomart Industries, Barjo Manufacturing, Perma Plating, Grand Novelty, Inc., and others filed petitions throughout 1957 for National Labor Relations Board decertification votes.

The process was not as easy. At Emenee Toy Co. nearly 200 workers were called back to the shop after they staged a wildcat strike and Local 222 threatened workers with lay off if they did not withdraw the NLRB petition. After months of delays and preemptive wage concessions the decertification vote lost but workers gained a 25% raise and some health benefits.[9]

JWU and other large operators with corrupt locals was not the only problem. ILGWU, Teamsters, IBEW and the Meat Cutters had some local that received complaints. ILGWU in particular was singled out for having locals that did little to move workers, the majority of them Puerto Rican women, out of the $45/week minimum wages mandated by the union contract. Workers under contract went “unserviced” for years and employers could determine workloads freely, while firing those complaining when vacation or holiday pay was not fulfilled. ACTU concluded, probably in an exaggerated mode so typical of its denunciations, that “very few unions, even the legitimate ones, are solicitous of their Puerto Rican members.”[10]

By the spring of 1957, ACTU had encouraged a torrent of protest and mobilization. The workers of nineteen factories were involved, and more would join in. ACTU tactics combined legal strategies with direct militant action at workplaces followed by a campaign of letter writing and public protest. Their efforts received increased attention when Puerto Rican workers went to picket the AFL-CIO’s second national convention in Atlantic City for inaction in ridding the New York City labor movement of corrupt locals.[11] A few months later AFL-CIO president Meany claimed to be shocked by reports in the New York Times that Puerto Ricans when seeking jobs from employment offices requested non-union jobs because of the “bad name given to unions by racketeers and ‘sweetheart’ contracts.”[12]

By the spring of 1957, ACTU had encouraged a torrent of protest and mobilization. The workers of nineteen factories were involved, and more would join in. ACTU tactics combined legal strategies with direct militant action at workplaces followed by a campaign of letter writing and public protest. Their efforts received increased attention when Puerto Rican workers went to picket the AFL-CIO’s second national convention in Atlantic City for inaction in ridding the New York City labor movement of corrupt locals.[11] A few months later AFL-CIO president Meany claimed to be shocked by reports in the New York Times that Puerto Ricans when seeking jobs from employment offices requested non-union jobs because of the “bad name given to unions by racketeers and ‘sweetheart’ contracts.”[12]

In coordination with workers and the ACTU in 1957, the Spanish language press, the Migration Division, the Mayor’s Committee, and other entities began logging complaint cases with the AFL-CIO itself. After its own central review of these complaints the AFL-CIO took its own tally of the massive work that had to be done.

Both Spanish language dailies ran daily stories and columns on the labor fights to end “exploitation.” El Diario provided an outlet for grievances, which allowed journalist Jose Lumen Roman to magnify and perhaps multiply the initial efforts of workers, lending support and legitimacy to their complaints. Complaints were referred to unions, the CLC, the MD and other agencies and and Lumen himself presented hundreds of complaint letters when he testified in Congress at the McClellan hearings. For years, he kept the complaints and demands of Latino workers on the front cover of El Diario.

Diario-11-march-1956

Between 1953 and the early 1960s, workers, unions, and their allies carried out a pitched fight against the corrupt racket unions typical of the low-wage, low-skill factories described above. The process became the center of Puerto Rican-labor movement relationship at many levels, mobilizing the resources that other Puerto Rican gained from membership in higher skill, higher-pay positions and their membership in legitimate unions. The critical piece in this linkage was the support of the Central Labor Council—a consensus emerged among these leaders that the problem was simultaneously political, moral, and economic and could be framed as one central to the core goals and principles of the labor movement.

The Central Labor Council and the AFL-CIO

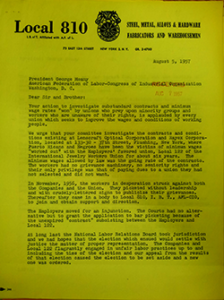

Once the ACTU and Migration Division got things going in 1956, and with the support of IUE locals, IBEW Local 3 and District 65 leaders, the soon-to-be merged local CIO and AFL Central Labor Councils placed the fight against exploitation and in support of Puerto Rican workers as its principal goal by 1957. Central Labor Council leaders committed to supporting low-wage workers and Puerto Rican “newcomers” and pushed other unions to name representatives to the “Spanish” work while joining the ACTU in pressing the AFL-CIO president to expel corrupt internationals and supporting aggressive tactics against racket unions. Member unions were urged to name representatives to the Spanish or Puerto Rican work.

Once the ACTU and Migration Division got things going in 1956, and with the support of IUE locals, IBEW Local 3 and District 65 leaders, the soon-to-be merged local CIO and AFL Central Labor Councils placed the fight against exploitation and in support of Puerto Rican workers as its principal goal by 1957. Central Labor Council leaders committed to supporting low-wage workers and Puerto Rican “newcomers” and pushed other unions to name representatives to the “Spanish” work while joining the ACTU in pressing the AFL-CIO president to expel corrupt internationals and supporting aggressive tactics against racket unions. Member unions were urged to name representatives to the Spanish or Puerto Rican work.

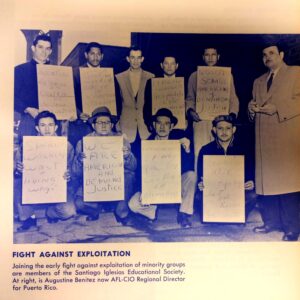

By April and May 1957, sufficient pressure had been put on the AFL-CIO national leadership, and by June, the newly merged CLC and AFL-CIO national office staff had worked out a strategy. In 1957, the CLC established the AFL-CIO’s Committee to End the Exploitation of Puerto Ricans and Other Minority Group Members, with official sanction and the authority to figure out jurisdictional disputes between unions. Behind this transition lay Harry Van Arsdale’s pressure to move forward in responding to the challenge in hand.[13] Throughout 1959, the effort to “liberate” exploited minority workers was the CLC’s singular priority. Further pressure from the Central Labor Council, the Migration Division, and workers themselves led the AFL-CIO national office to fund a full-time Spanish-speaking organizer.[14] In November 1959, AFL-CIO President Meany appointed Agustin (Gus) Benitez, a 20-year labor movement veteran, to this work.[15] He became the broker for the CLC and its member unions, receiving complaints directly from the media, MD, MCE, and workers themselves.[16] IBEW leader Paul Sanchez took over this position in 1962 and served until 1967.

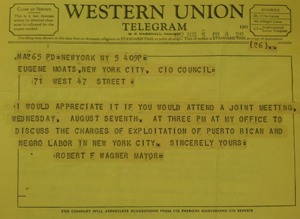

The Mayor’s Committee against Exploitation

A s a response to the emerging rebellion, Mayor Wagner created a Committee against Exploitation in August 1957 which drew members from government agencies, labor unions, business and community groups, including Monserrat from the Migration Division. The MCE face an daunting task, with CLC-leader Morris Iushewitz and the Migration Division’s Monserrat telling journalists upon the inauguration of this committee that they had already had “enormous files of complaints” In its first month the MCE received 500 complaints, which the staff reviewed and referred to various agencies including the District Attorneys for further action. In 1959, the Committee expanded from simply handling referrals to actively pursuing their own investigations.[18]

s a response to the emerging rebellion, Mayor Wagner created a Committee against Exploitation in August 1957 which drew members from government agencies, labor unions, business and community groups, including Monserrat from the Migration Division. The MCE face an daunting task, with CLC-leader Morris Iushewitz and the Migration Division’s Monserrat telling journalists upon the inauguration of this committee that they had already had “enormous files of complaints” In its first month the MCE received 500 complaints, which the staff reviewed and referred to various agencies including the District Attorneys for further action. In 1959, the Committee expanded from simply handling referrals to actively pursuing their own investigations.[18]

The Mayor’s Committee against Exploitation provided a bridge between the anti-racket labor activists. It provided inter-agency support that included federal wages and hours enforcement, legal support, indictments by District Attorneys, and other forms of organizational assistance. Wagner ordered the heads of his departments to collaborate with the efforts, including the welfare department, to help out striking workers left without incomes, and opened multiple offices and expanded staff between 1959 and 1962.[19]The office was led by George Santiago, borrowed from the leadership of IBEW Local 3.[20]

The Industrial Unions

Repeatedly, the IUE and D65 and IBEW proved to be the most militant, even vehement organizers of the minimum wage plants run by racketeers, responding to as many worker demands as possible. Throughout 1957, they responded most quickly to requests by ACTU, Lumen Roman, the Migration Division and workers themselves for organizing protests and decertification votes. Their commitment did not just entail a desire to organize low-wage workers. Still, it was also driven by their perception—highlighted as a common sense idea by the Spanish Language press and the Migration Division—that the exploitation of Puerto Rican migrant workers was also a civil rights issue in which thousands of recent arrival immigrants, many with low or no skills in English, were taken advantage of by bosses and racketeers. All the same, it had taken a confluence of forces for these workers to see that they had allies, and the explosion of complaints and mobilizations between 1957 and 1960 was comparable to the organizing drive of the immediate post-war years, with which these unions created their post-war successes.

Repeatedly, the IUE and D65 and IBEW proved to be the most militant, even vehement organizers of the minimum wage plants run by racketeers, responding to as many worker demands as possible. Throughout 1957, they responded most quickly to requests by ACTU, Lumen Roman, the Migration Division and workers themselves for organizing protests and decertification votes. Their commitment did not just entail a desire to organize low-wage workers. Still, it was also driven by their perception—highlighted as a common sense idea by the Spanish Language press and the Migration Division—that the exploitation of Puerto Rican migrant workers was also a civil rights issue in which thousands of recent arrival immigrants, many with low or no skills in English, were taken advantage of by bosses and racketeers. All the same, it had taken a confluence of forces for these workers to see that they had allies, and the explosion of complaints and mobilizations between 1957 and 1960 was comparable to the organizing drive of the immediate post-war years, with which these unions created their post-war successes.

Conflicts at Jansa Woodworking in Brooklyn, Metzger and Style Rite Optical were examples of the intense organizing battles involving multiple unions, outside allies, the NLRB and the employers. At Style Rite, Mario Abreu, District 65’s organizer, worked to free the 300 workers from their union, another corrupt local of the IJWU. The twin plants, one in Brooklyn and one in the garment district, exchanged workloads. Workers had started a strike in June when the plant owners said they were moving the plant to Queens but workers, led by Luisa Diaz, refused to support the move and instead contacted Abreu. When they brought in District 65 the union immediately negotiated a $5 weekly increase (12%) and another $3 after the first year with a minimum salary of $50.[21]

The mobilization of low-wage Puerto Rican workers and the labor movement response encouraged other efforts to organize and improve conditions throughout similar if better organized, sectors in NYC. Garment workers, organized mainly by ILGWU and Amalgamated, were an important part of the process. In 1957, four hundred mostly Puerto Rican workers from a Bronx factory picketed the ILGWU headquarters, alleging inadequate representation. In 1958, two hundred workers at Plastic Wear, organized by ILGWU Local 132 also in the Bronx, demonstrated against the exclusive use of English in the local’s meetings when 80% of the workers were Spanish speakers. Workers at the Q-T Knitwear Co., represented by the same local, carried out a wildcat strike and picketed ILGWU headquarters, alleging a sweetheart contract and the failure to hold meetings in Spanish.[22]

The text is copyrighted by the author, 2025.

Users may cite with attribution.

[3] “Exploitation of Puerto Ricans.” Labor Law Journal 1, no. 6 (1950): 469; Wage Thieves Facing Big Fine New York Amsterdam News, 11 October 1952, 21.

[4] Position Paper, Jesus Colon Collection, Centro Archive.

[5] See “Need for Labor Education in Puerto Rico.” Memphis World, 12 September 1959.

[6] Norman C. DeWeaver, “ACTU Labor Schools for Spanish-Speaking,” America, (1955), 452

[8] Complaint files, Collection, Series 4, File 20/11, Collection RG1-027, AFL-CIO Archive, University of Maryland Special Collections.

[9] “Puerto Ricans Victoriously Defeat Racketeers,” The Labor Leader, November-December 1957; “249 trabajadores optan por permanecer en unión,” El Diario, 26 November 1957.

[10] “Puerto Rican workers victims of racketeers,” The Labor Leader, December 1956.

[11] John C. Cort, Dreadful Conversions: The Making of a Catholic Socialist (New York: Fordham University Press, 2003).

[12] Weekly Report, Clarence Senior to Blas Olveras, 6 November 1957, Box 2948, OGPRUS, Centro Archive.

[13] Michael Mann, Director, Region II, AFL and CIO to Peter Mcgavin, 21 April 1959, AFL-CIO Collection, University of Maryland Special Collections.

[14] Hutchinson, John. The Imperfect Union; a History of Corruption in American Trade Unions. New York: Dutton, 1972, 328-333

[15] “AFL CIO Wages War on Racket Unions.” The Labor Leader, November 1959.

[16] “200 hispanos declaran huelga en fabrica Bronx,” El Diario, 17 August 1960.

[18] New York City, Department of Labor, Annual Report, 1959, 33-34.

[19] New York City, Department of Labor, Annual Report, 1961, 28-29; New York City, Department of Labor, Annual Report, 1962, 9-10.

[20] Gray, Lois. “Case Study No. 7: The Puerto Rican Workers in New York.” In Joint International Seminar on Adoption of Rural and Foreign Workers to Industry. Paris: Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development, Manpower and Social Affairs Directorate, 1965.

[21] 300 trabajadores ópticos logran arreglar huelga por gestión Mario Abreu,” El Diario, 30 Julio 1957; Levitas, “Timetable of Revolution,” Article VI, New York Post, 20 July 1957.

[22] Ortiz, Altagracia. “Puerto Rican Workers in the Garment Industry of New York City, 1920-1960.” In Labor Divided: Race and Ethnicity in United States Labor Struggles, 1835-1960, edited by Robert; Stephenson Asher, Charles. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990, 117; Michael Luis Ristorucci. “Some observations on the Hispanic labor committee, the labor movement, and post-World War II Latino labor activism in the metropolitan New York area.” Harry Van Arsdale Junior Memorial Foundation, 2002.