The Torres Ortiz Family: American Immigrants

Natalie Saldarriaga

Introduction

The United States has long been a nation of immigrants. From its conception, immigrants arrived on the search for something better than what they knew at home. The first immigrants to arrive were white Europeans in search for religious freedom, but those that followed arrived with reasons unique to each individual. But what united these vastly different people were their citizenship or lack thereof. Whether they came from England, Germany, or China, by law, they were not citizens of the country. Depending on the time period, even some who were born in America were not considered citizens either, such as Native Americans and African Americans. By law, they were strangers and, to some, may have been considered disadvantaged. Not only did they leave everything they knew behind or were treated unfairly in the only land they knew, but these individuals would not be recognized as whole and legitimate persons. They would be characterized as the “other” and would need to depend on changes in legislation or sneaking around laws to gain citizenship in the country. This concept of citizenship is important in the United States because it opens doors that are often shut and sealed to those who aren’t. But what happens when you are American by law, and not in culture? What happens when through a shift of colonial power, out of your control or even understanding, you are given American citizenship? This is what happened to Puerto Ricans in the 20th century.

In my paper I would like to understand the Puerto Rican immigrant experience. In what ways did their citizenship set them apart from other migrant groups? To grapple with this question, I will focus on a single family: The Torres-Ortiz family. This family’s American story begins like many other Puerto Rican families in East Harlem, but it also differs in that they moved as a unit and individually to different parts of the United States. In retelling the story of this family, I hope to not only understand the factors in Puerto Rico that pushed such a great number to leave the island, but also what life was like in New York for them. How did the proximity to the island make the immigrant experience different than that of the European experience? And lastly, through the Torres-Ortiz family, I’d like to understand how they navigated throughout the United States and kept their Puerto Rican identity alive in environments outside of the Puerto Rican hub of New York City.

Life on the Island

Gerardo Antonio del Carmen Torres-Diaz was born under Spanish rule on November 30th, 1891, in San Juan, Puerto Rico.[1] Gerardo was born during the last few decades of Spanish rule when political reform in Puerto Rico was turbulent. In 1873, the constitutional monarchy was replaced by a republican government, but only a year later, the new government fell, resulting in a military coup, giving rise to the Spanish monarchy again. Puerto Rico returned to its colonial status under appointed governor Jose Laureano Sanz who overturned all democratic practices.[2] Born seven years before the signing of the Treaty of Paris, a treaty that would end the Spanish-American War and place Puerto Rico under US control, Gerardo would come of age in a Puerto Rico much different than the one he knew as a child.[3]

His father, Sandalio Torres Monge, was twenty-two years old when he was born, and his mother, Dolores Diaz, was sixteen years old.[4] The social class that Gerardo was born into is not entirely clear, but it does seem that his family was better off than most. Sandalio, his father, was an attorney whose courtroom work was documented in Decisiones de Puerto Rico: Compliacion de Sentencias Y Resolucciones Dictadas Por El Tribunal Supremo de Puerto Rico. Within the publication, there were cases cited, and one of them is Sandalio’s 1903 case, where he defended a man whose wife had fled from home and failed to show up in court to divorce him.[5] Those engaged in professional service on the island were considered to be part of the top five prevalent social/occupational groups.[6] Lawyers made up a part of the upper middle class. Another indicator of his class standing was his ability to read and write as indicated in the 1920 U.S. Census, along with his mother who was also identified as literate.[7]

Maria Louisa Ortiz-Sedano was the first in the Torres-Ortiz family to be born in a US-ruled Puerto Rico. She was born on October 17th, 1899, to Felipe Ortiz, who hailed from Castro Urdiales, a Spanish northern seaport, and Dolores Sedano, who was from Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic.[8] Maria Louisa’s family upbringing is not clear but as an adult in Puerto Rico she was politically active. In 1931 she donated money to the Union de Puerto Rico.[9] That same year in a letter she is addressed as “presidente sub junta de damas ‘Seccion Sur’” of the Liberal Party of Puerto Rico. She was the president of the women’s section of the Southern part of San Juan.[10] Maria Louisa’s participation in the Liberal Party gives great insight into how some Puerto Ricans felt about their situation. The island shifted from one colonial power to another, but they never lost their own national identity. They understood that as a country they deserved the right make decisions for their own people. Even more so, it is nice to see that as a woman, Maria Louisa’s voice and opinion were valued so much that she was in charge of other women who felt the same way.

Ciudadanía Americana–“American Citizenship”

Although Maria Louisa was born after the US took over the island, it was not until she was seventeen that she would be granted US citizenship under the Jones Act. This new citizenship also came with enrollment in selective service draft for Puerto Rican men. As was required of him, Gerardo was inscribed into the army on July 5th, 1917, and almost a year later, on June 29th, he was married to Maria Louisa.[11] Two years later, they had their first child, Gerardo Rafael Torres-Ortiz Jr., born on May 6th, 1920.[12] At the time Geraldo was living with his wife and mother in Mercado, the district in San Juan. At the beginning of 1920 Gerardo was working as a furniture salesman, and by the time his first child was born he was an oficinista, meaning that he was an office worker.[13] Maria Louisa was not employed, but her mother-in-law was contributing to the household, although the particular job she held is unclear.[14] A little over a year later Gerardo and Maria Louisa welcomed their second child, Victor Manuel Simplicio Torres-Ortiz on August 26, 1921.[15] It is clear that Gerardo’s new and growing family had access to upward mobility. This could have resulted from Gerardo’s class background, but the jobs that Gerardo held kept the family in a better place than many others. As the years progressed, Gerardo’s jobs continued to improve. Seven years after the birth of Victor, Gerardo and Maria Louisa welcomed their third and last son, Fabio Ortiz-Torres, on July 31st, 1928. By this time, Gerardo was a postal worker, a job he would keep until his retirement.[16]

To the Mainland We Go

The Torres-Ortiz family were no strangers to traveling to the United States before their official move to New York. Gerardo Sr. was the first to travel to the US in 1938. He set sail on the S.S. San Juan heading to New York on September 7th- a five-day journey. The following year, Gerardo Sr. would make the same trip on September 14th but stayed in New York City.[17] He was housed with Enrique Monge, a relative from his grandmother’s side. Enrique was a divorced man living on West 42nd Street and Amsterdam Avenue, and through his position as a postal clerk, it is possible that he helped his distant relative find a job in the United States.[18] In 1940 Gerardo Sr. permanently relocated his family to New York City. The S.S. San Jacinto with a fare of $25 arrived on October 24th, 1941, but Gerardo Jr. and Victor were not on board.[19]

By this time, Gerardo Jr. (who goes by Gerry) and Victor were of college age and had traveled to the US to go to college. After sailing from Mayaguez on August 24th, 1940, and arriving in New Orleans on September 1st, the Torres-Ortiz brothers went their separate ways.[20] Gerry was enrolled at the University of Alabama and studied engineering, while Victor was enrolled at Spring Hill College in Spring Hill, Alabama.[21] The enrollment of Puerto Ricans in Southern institutions was not uncommon. In 1902 President Theodore Roosevelt appointed University of Pennsylvania professor Samuel McCune Lindsay as the island’s education commissioner.[22] His legislation specified that Puerto Rican students would attend primer model African American industrial and agricultural training and also normal schools. Section 73 of the school law “specified that ‘the colleges and institutions designed for these students to carry out their studies, shall be the Hampton Institute, Virginia, and Tuskegee Institute, in Tuskegee, Alabama; as well as other similar educational institutions’.”[23] This school law was an early example of Puerto Ricans migrating to the United States to receive an education. But the institutions listed under the school law were black institutions, much different than the University of Alabama and Spring Hill College which were predominantly white.

Puerto Ricans and Race

The education system in the US racially discriminated against Hispanic students with a contradictory legal history of access and segregation. In the 1940s in places such as Orange County, California, 80 percent of Latino children attended separate schools.[24] So how were Gerry and Victor able to attend college in Alabama? Their admission likely meant that they were perceived as white, although in personal correspondences, they do not address the color issue at all. In a postcard sent home from school Gerry writes “Por acá todo bien. Exámenes a montones. Estoy tomando [sic] un laboratorio queme coje todo el tiempo. Después te contare.”[25] He assures his mother that everything is fine at school, that he’s just been busy taking exams and a lab that he’ll tell her more about later. He sounds like any other university student writing home to his parents, worried about school work and not racial tensions in the South.

The classification of race in Puerto Rico has always been complicated. Color and racial characteristics range from white to black and multiple variations in-between. “blanco/a” was applied to those with light skin and European phenotypes, “persona de color” was used describe those with dark skin and African phenotypes, but there was some difficulty in trying to identify people who were in between white and black.[26] The most often used term was “trigueno”, the term is a Spanish word that means the color of wheat. The term was originally used to identify a person who had a dark complexion but European features. And although triguenos were considered “handsome or beautiful” it was still white Puerto Ricans who held privileges over other races.[27] Traditionally, the upper class always prided itself on being white and had always been sensitive towards the topic of color and race characteristics. In the Torres-Ortiz family all family members were identified as “de rasa blanca” on their birth certificates and US census.[28] And given their middle-class background, they were able to have social status not only in Puerto Rico but also in the US.

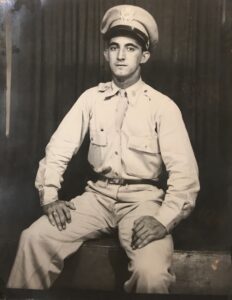

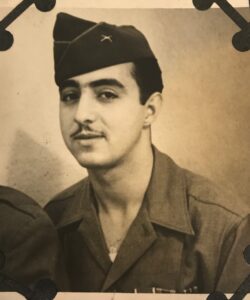

During World War II, the US Army was segregated. Victor was enlisted into the US Army on May 17th, 1943, and participated in the invasion of Normandy the following year.[29] In photographs he sent his girlfriend at the time, he is posing with a grin next to his fellow white soldiers. Many US Latinos were categorized as white, meaning that white-Puerto Ricans were placed in white battalions instead of black battalions where darker-skinned Puerto Ricans from New York City would be placed. [30] This is not to say that the racial lines were always clear; army veteran Manny Diaz was assigned to a white battalion but had cousins with blue eyes and blonde hair end up in black battalions.[31] But despite Victor’s racial classification in the army, he still experienced racial discrimination. World War II veteran Alfonso Rodriguez remembered the discrimination he faced in the military when he was told to speak English “like Americans” by a white solider, while speaking in Spanish to a fellow Hispanic solider.[32] Alfonso’s experience speaks to the nativism present in regards to how white-Americans viewed Hispanic-Americans.

Did Gerry and Victor experience racism? We don’t know, but the fact that Gerry was elected Student Member of the Society of American Military Engineers in Jim Crow Alabama demonstrates the successful integration of elite soldiers into white culture of education and military in the US.[33] Having been able to speak English prior to college and with phenotypes closer to those of Europe than Africa, the brothers’ identity as white was never in doubt within their battalions enough to have had a good experience in the US as Puerto Ricans.[34]

En Nueva York Me Críe Pero Nunca Me Olvidare de Mi Tierra Borinqueña[35]

“I Was Raised in New York But I’ll Never Forget My Puerto Rican Homeland”

New York City has long been described as the financial and cultural capital of the world.[36] With its vast population of entrepreneurs, teachers, taxi-drivers, doctors, and artists it’s no wonder it has been home to millions of immigrants. Whether their first encounter with the city be reaching dock or descending into an airport, New York has always been a place where new lives begin. Although in its most idealized state, it has come to symbolize what America has always wanted to be, there is no mistaking that those who migrate to New York shape the city in their own ways.

Back in New York City the Torres-Ortiz family arrived a few years before the Great Migration. After World War II, air service between San Juan and New York City was introduced, and migration between the island and the city transformed. In 1945, 13,500 immigrants entered the city, and the following year, almost 40,000.[37] What drove the Torres-Ortiz family to leave Puerto Rico behind is unclear, but in general economic factors were unquestionably one of the biggest that led to the Great Migration. By the end of the decade, those who migrated to New York City were between fifteen to forty-four years old, more educated than average, and usually from urban areas.[38] The Torres-Ortiz family fit well within the average immigrant mold, except that their elite education probably put them in a higher migrant hierarchy.

In 1942 the family settled into 524 West 134th Street. The neighborhood in which the family moved into was typical for better off Cuban and Puerto Rican families.[39] That same year Maria Louisa gave birth to her last child and only daughter, Mary Louise Torres-Ortiz who would go by Cookie for short.[40] Gerardo Sr. was working at the James A. Farley Post Office on 8th avenue.[41] A job at the postal office was attractive to immigrants because it meant not only regular salary but also job security, retirement pension and status within the community.[42]

Other than make their way into government jobs, Puerto Ricans would also transform East Harlem to be their home away from home. Puerto Ricans never shied away from maintaining their roots in the city. The creation of El Barrio ensued even before the Great Migration of the late 1940’s. El Barrio, Spanish for the neighborhood, spans from 96th Street to East 125th Street. Even though the Torres-Ortiz family arrived to New York a few years before the Great Migration, they did take part in preserving Puerto Rican culture on the mainland. In May of 1945 Gerardo Sr. and Maria Louisa attended the Miembros de la Colonia Puertorriqueña en Nueva York event held in Audubon Hall on West 163rd Street to say farewell to “los compeones ‘Guantes Dorados’”.[43]

Puerto Rican-centered clubs and associations were not foreign to Gerardo Sr. In 1950, he was one of the founding members of The Puerto Rican Veterans Welfare Postal Workers Association. Its main objective was to “promote friendship and encourage social and welfare intercourse among veterans born in Puerto Rico and their families who are employed in the Postal Service. To give aid in case of sickness and assistance in distress”.[44] The association held its meetings at 2 p.m. on the 3rd Sunday of every month except during the summer. To become a member one needed to be endorsed by a “member in good standing.” There was also a 50 cent initiation fee and $1.00 fee for the organization’s sick benefits to be paid monthly in advance. The sick benefits were twelve dollars a week that would be “paid to each member in case of sickness or accident for which reason being incapacitated to perform any work.” To receive these benefits a member needed to be in good standing for at least 6 months.

Puerto Ricans were aware of the deep connection between New York and Puerto Rico. They could see that East Harlem had been transformed because of their arrival. But that did not mean that Americans received the change with open arms.

Soon after the post-war wave of immigrants, “The Puerto Rican Problem” began to emerge. In February of 1947, the New York tabloid PM criticized the Puerto Rican government “for not controlling this massive exodus of people.”[45] Suggestions began to form as to how the government would be able to reduce the problem. The suggestions were to promise work in other cities in the country, job training programs, child and adult education, and social programs. But it was also suggested that Puerto Rico begin to solve its own problems so it’s citizens would see no need to leave and inhabit New York.[46]

Puerto Ricans did not create any problems that were not already familiar to Italian, Jewish, and African American communities from years before. Regardless of the similarities between New York immigrant groups and the ways in which they were initially perceived, Puerto Ricans still differ greatly. One of the biggest and most prominent differences is the proximity of New York to the island. For other migrant groups, a journey home usually meant failure and defeat, but for Puerto Ricans, going back to the island was much more casual.[47] This made for strong ties between their native land and new home. This also meant that Puerto Ricans assimilated much less into American society than other groups.[48] It can also be said that their American citizenship is what put them in such an odd place. They could continue to be loyal to their native land because there were no threatening motivations to become Americanized. They could hold on tightly to their Puerto Rican roots and continue to be American citizens. And if Puerto Rico began to seem like a far-away place, a summer spent with abuela and all of your primos would surely help you reconnect with your roots.

Westward We Go

The Torres-Ortiz family did not spend a significant amount of time living in New York, nor did it seem that they had any particular attachment to the city. Gerry was the first family member to leave New York behind. He was stationed in Panama and would meet and marry his wife Maye Mable Sanguinetti Torres.[49] Born on May 19th 1918 in Panama City, Maye was divorced and had two children. In 1949 she petitioned for naturalization listing her residence with Gerry and her children as 244 Rutledge Street in San Francisco, California.[50] With his new family on the west coast, Gerardo was ready to move the rest of his family over. In a letter written in June of 1951, Gerry reveals to his intentions to his brother Victor:

“I want to bring my folks to the West Coast and either build them or buy them a house or a small ranch and I want it done this summer. Yes this summer. Vicky see if you can sell the apartment and just keep what what mom wants to keep… Please listen to me, Vicky, you can get a job here too… Papa can kiss his job goodbye and come on over. This is the dream of my life and finally to open a bar as soon as there’s money and a Fabio to take care of it”[51]

It would take a couple of years for Gerry’s dream to become a reality, but it would surely happen, though not in the ways in which he expected.

Gerardo Sr. developed lung cancer and was the next family member to move to the West Coast, leaving his wife and other children behind.[52] By 1954 Gerardo retired from his career as a postal worker and the same year. The Puerto Rican Veterans Welfare Postal Association had a “Get Together Meeting” to say farewell to now-president Gerardo Sr. The following month Gerardo Sr. would board a Trans World Airlines flight to San Francisco.[53] His health quickly deteriorated and he was emitted into The Veterans Hospital in Oakland, California.[54] On March 23, 1955, Gerardo Sr. passed away, and following his death, the rest of the Torres-Ortiz family moved to San Francisco.[55]

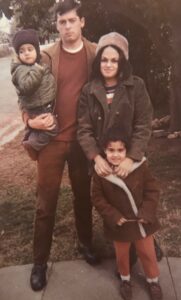

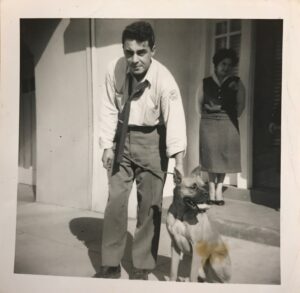

All the Torres-Ortiz children would grow and create their own lives in San Francisco. But Mary Louise is by far the most mysterious of the Torres-Ortiz clan. Her family and friends only mention her in the closing of letters, “besitos a Cookie,” kisses for Cookie.[56] The only proof of her existence are of photographs left behind. They document her life in ways that the vast correspondences and government records the rest of the family has, does not. She was photographed as an infant bundled up in the arms of her middle-aged parents. As a toddler, she poses on the roof of an apartment building, holding a Nazi flag and welcoming her brother Victor back from war. In an elementary school picture she grins wearing a collared-dress and dangling earrings. She’s photographed in Puerto Rico posing in front of a parked cars with a cigarette in hand, her face telling of her young age. In 1962 she would marry Gilbert Shine in Saint Isadore Church in Yuba City, California.[57] And in 1968 she appeared in a colored photograph with her husband and two children, Sharon and Robert.

Why is it that Mary Louise didn’t leave behind letters or journals? Is she still alive and has held on to everything? Or did she feel that her paper trail would not be significant enough to keep? Did the US fail to make Mary Louise’s government documents accessible in comparison to her father and brothers? Whatever the case may be, she’s the family member I wish I knew more about because her experience was so different from that of the rest of the family. Born in New York, she wouldn’t experience leaving Puerto Rico behind to start over in a new country. What was it like for her to possibly be perceived as a foreigner due to her appearance but only know life in the US? How was she able to incorporate both cultures into her life? The photographs of her say so much, while they also say nothing at all.

Life in the Bay Area

Puerto Ricans are not strangers to San Francisco. There has been a presence of Puerto Ricans since the early 20th century, due to recruitment as contracted agricultural workers in Hawaiian sugarcane fields.[58] In San Francisco, Gerry was a part of the restaurant business. Within his belongings, I found a business card for Scotty’s Drive-in, “home of the foot-long hot dog,” and best hamburgers in the city.[59] Gerry was the proprietor of the business located near the Golden Gate Bridge. Victor, on the other hand, was in the radio business. He was sport director and representative of KBRG radio station. Through his time at KBRG, Victor was able to bring “Major League Baseball to the Latin-American fans of the Bay Area and Northern California” by conducting broadcasts in Spanish.[60] In a handwritten note, Victor listed many reasons as to why KBRG was such a unique radio station. One of the reasons was that out of the 1,100,00 Spanish speakers living near KBRG’s listening area “almost half of them speak English but even they prefer to be addressed in their native language, Spanish.”[61] Listening to KBRG was one of the ways in which immigrant communities were able to connect to their cultures while living in the United States. It also allowed them to connect with other Hispanics who may not have been from the same country, but had the same interests, just as Victor was.

Fabio also experienced some success while living in San Francisco. The youngest Torres-Ortiz brother was chairman of a beauty pageant called “The Latin American Fiesta of 1968”.[62] The pageant began with a parade on Mission Street and the winner was announced at the Coronation Ball on May 18th, held at the San Francisco Hotel.[63] When asked by Mission District News as to why he put the pageant together, Fabio responded “to have something for everyone. And, by ‘everyone’ we certainly mean children too.”[64] The following day on May 19th, a Fiesta Mass was held at St. Anthony’s Church for the pageant winner.[65] Fabio’s beauty pageant was a way for immigrant groups to create their own traditions in the US.

Fabio also experienced some success while living in San Francisco. The youngest Torres-Ortiz brother was chairman of a beauty pageant called “The Latin American Fiesta of 1968”.[62] The pageant began with a parade on Mission Street and the winner was announced at the Coronation Ball on May 18th, held at the San Francisco Hotel.[63] When asked by Mission District News as to why he put the pageant together, Fabio responded “to have something for everyone. And, by ‘everyone’ we certainly mean children too.”[64] The following day on May 19th, a Fiesta Mass was held at St. Anthony’s Church for the pageant winner.[65] Fabio’s beauty pageant was a way for immigrant groups to create their own traditions in the US.

Life for Maria Louisa after her husband’s death is not documented, nor is much else of the family either. Whether or not Gerry got around to building his family a house is not clear, though the Torres-Ortiz brothers did live in San Francisco for the rest of their lives. Fabio and Victor both passed away in 1997 and Gerry died in September of 2005.[66] Both Fabio and Gerardo Sr. were buried in Puerto Rico, showcasing the strong ties the men had to their homeland.[67] Despite the life they built for themselves in the US, Puerto Rico was always home to them, so much so that the island would be their final resting place. Information on when Maria Louisa died I could not find, but there was a letter addressed to her from California Senator Milton Marks, a friend of Fabio.[68] In it Marks says that he heard Maria Louisa was ill and hoped “that each day finds you better and that you will soon be fine again.”[69] At the time of the letter Maria Louisa was nearing 76 years old, so it is possible to assume that she might have passed sometime around the late 70’s. As for Cookie, I do not have any information on when she passed or if she is still living.

Reflections

The reason why I chose to write about a Puerto Rican family was because I wanted to understand how they were as American citizens, able to occupy space within Jim Crow America. Usually in the re-telling of mid-20th century America, the narrative seems to typically be whites vs. African Americans. But I figured that there were so many others who did not identify with either, that had to find a way to exist in the country. And although the Torres-Ortiz family did answer a lot of my initial questions, they also made me confront stereotypes I had of the Puerto Rican experience in the US.

Initially, I chose this specific family because I felt that with the correspondence and documentation they left behind, I would have enough information to piece together a puzzle. But the more I learned about this family, the less I felt I knew their story, and this came from what I was expecting of them. I expected this family to come from a lower-class background in Puerto Rico, to constantly be grouped in with African Americans, and to have a hard time assimilating into American society. I began to feel wrong for telling the story of a well-off family, while there were so many others whose stories were glossed over by history. But later, I realized that in having these preconceived notions, I was putting Puerto Rican immigrants into one box, just as many immigrants are constantly being put into.

Immigrants are complex people with difficult stories that don’t always compare to one another. Once I was able to let go of these expectations and take the family’s story for what it is, I realized I WAS telling the Puerto Rican immigrant story. In learning that Victor was placed into a white battalion, I was able to discuss the discrimination Puerto Ricans faced in the army. And in learning that Fabio put together a beauty pageant, I was able to discuss how Puerto Ricans found ways to celebrate their culture while living in the US. I didn’t have to tell the story of a lower-class family exclusively to tell an authentic Puerto Rican story.[70]

The text is copyrighted by the author, 2025. All photos by permission, Center for Puerto Rican Studies, 2017.

Users may cite with attribution.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Diaz, Manny. interview by Lillian Jimenez. Hunter College Centro, March 14, 2001.

Hildebrand, Evie. U.S. Census of 1940. United States Federal Census.

Jesus Colon Papers, 1901-1974. Hunter College Centro Archives, Hunter College Libraries.

Ortiz-Sedano, Maria Louisa. Registro Civil 1805-2001, Puerto Rico. Certificate of birth. https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QV1Y-J1KJ.

Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, 1925-1957. Arrival September 12. 1938. https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&dbid=60882&h=92065&tid=&pid=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=Jym599&_phstart=successSource.

Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, 1820-1957. Arrival September 18, 1939.https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&dbid=7488&h=1004600513&tid=&pid=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=Jym601&_phstart=successSource.

Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at San Juan, Puerto Rico, 1901-1962. Departing from New York on October 5, 1939. https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&dbid=7488&h=1004600513&tid=&pid=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=Jym601&_phstart=successSource.

Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, 1813-1963. Arrival September 1, 1940. Ancestry.com

Shine, Glibert and Mary Louise Torres. California Marriage Index, 1960-1985. Certificate of marriage. Ancestry.com

Torres Diaz, Gerardo. U.S. Census of 1920. United States Federal Census. https://search.ancestry.com/cgibinsse.dllindiv=1&dbid=6061&h=59733455&tid=&pid=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=Jym516&_phstart=successSource.

Torres-Diaz, Gerardo. U.S. Census of 1940. United States Federal Census. Ancestry.com

Torres, Gerardo. U.S. Veterans’ Gravesites, 1775-2006. Cemetery address. Ancestry.com

Torres Diaz, Gerardo Antonio del Carmen. Registro Civil, 1805-2001, Puerto Rico. Certificate of birth. https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:9Q97-YSDP-V1B?cc=1682798&wc=9PR5-K68%3A131388001%2C145785701.

Torres, Gerardo and Maria Louisa Ortiz. Registro Civil 1836-2001 Puerto Rico. Certificate of marriage. Ancestry.com

Torres Monge, Sandalio. Registro Civil 1805-2001, Puerto Rico. Certificate of birth. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QVPM-LKSY.

Torres Y Monge, Sandalio and Ana Angela Figueroa Y Reyes. Registro Civil 1805-2001, Puerto Rico. Certificate of marriage.

Torres-Ortiz Family Collection, 1911-1975. Hunter College Centro Archives, Hunter College Libraries.

Torres, Fabio. BIRLS Death File, 1850-2010. Death record. Ancestry.com

Torres, Fabio Ortiz. Registro Civil 1805-2001, Puerto Rico. Certificate of birth.. https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:9Q97-YSDN-ZB9cc=1682798&wc=9PRG-MNL%3A131388001%2C146767501.

Torres, Fabio O. U.S. Veterans’ Gravesites, 1775-2006. Cemetery address. Ancestry.com

Torres-Ortiz, Gerardo Rafael. Registro Civil 1805-2001, Puerto Rico. Certificate of birth..

Torres, Victor. BIRLS Death File, 1850-2010. Death record. Ancestry.com

Torres-Ortiz, Victor Manuel Simplico. Registro Civil 1805-2001, Puerto Rico. Certificate of birth. https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:9Q97-YSDF-Y5W?cc=1682798&wc=9PRL-T38%3A131388001%2C137952001.

Torres-Sanguinetti, Maye Mabel. California Federal Naturalization Records, 1843-1999. Petition for naturalization. Ancestry.com

Secondary Sources

Baruch College. “An Introduction to New York City (NYC) Culture.” https://web.archive.org/web/20130505181316/http://www.baruch.cuny.edu/nycdata/culture/intro.htm.

Blakemore, Erin. “The Brutal History of Anti-Latino Discrimination in America.” History. http://www.history.com/news/the-brutal-history-of-anti-latino-discrimination-in-america.

Boyd, Deanna and Kendra Chen. “The History and Experience of African Americans in America’s Postal Service.” National Postal Museum. https://postalmuseum.si.edu/AfricanAmericanhistory/p8.html.

Canales, Angel. Lejos de ti. New York: Alegre Records, 1975.

Castro, Antonio F. Decisiones de Puerto Rico: Compliacion de Sentencias Y Resolucciones Dictadas Por El Tribunal Supremo de Puerto Rico. San Juan: Law Library of Chicago, 1908.

del Moral, Solsiree. Negotiating Empire: The Cultural Politics of Schools in Puerto Rico, 1898-1952. Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2013.

Diaz, Daniella. “Trump: We cannot aid Puerto Rico ‘forever’.” CNN, October 12, 2017. http://www.cnn.com/2017/10/12/politics/donald-trump-puerto-rico-tweets/index.html.

El Museo. “El Barrio.” http://www.elmuseo.org/el-barrio/.

Fitzpatrick, Joseph P. “Attitudes of Puerto Ricans Toward Color.” The American Catholic Sociological Review 20, vol.3 (Autumn 1959): 219-233.

Franqui-Rivera, Harry. “So a new day has dawned for Porto Rico’s Jibaro: Military Service, manhood and self-government during World War I.” Latino Studies 13, no.2 (2015): 185-206.

Glazer, Nathan and Daniel Patrick Moynihan. Beyond the Melting Pot: The Negroes, Puerto Ricans, Jews, Italians, and Irish of New York City. Cambridge, M.A: The MIT Press, 1970.

Gonzales, Juan. Harvest of Empire: A History of Latinos in America. New York: Penguin, 2011.

Green, Alyssa. “Voices Oral History Project.” University of Texas Libraries.

Hunker, Henry L. “The Problem of Puerto Rican Migrations to the United States.” Ohio Journal of Science 51, no. 6 (November 1951): 342-346.

Korrol-Sanchez, Virgina E., From Colonia to Community: The History of Puerto Ricans in New York City, 1917-1948. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1983.

Lauria-Santiago, Aldo and Lorrin Thomas. Rethinking the Struggle for Puerto Rican Rights. Press, 2019.

Library of Congress. ““Party Consolidation and Civil Crisis.” https://www.loc.gov/collections/puerto-rico-books-and-pamphlets/articles-and-essays/nineteenth-century-puerto-rico/party-consolidation/.

Library of Congress. ”Politics and Reform in the Later Nineteenth Century.” https://www.loc.gov/collections/puerto-rico-books-and-pamphlets/articles-and-essays/nineteenth-century-puerto-rico/politics-and-reform/.

Library of Congress. “Treaty of Paris of 1898.” https://www.loc.gov/rr/hispanic/1898/treaty.html.

Mathieson, Catherine. “Voices Oral History Project.” University of Texas Libraries.http://www.lib.utexas.edu/voces/template-stories-indiv.html?work_urn=urn%3Autlol%3Awwlatin.261&work_title=Gonzalez%2C+Norberto+M.

Media, Nitza C. “Rebellion in the Bay: California’s First Puerto Ricans.” Centro Journal 13, no. 1 (Spring 2001): 85-95.

Puerto Rico. “Julia de Burgos-Activist and Poet.” http://www.puertorico.com/blog/julia-de-burgos-activist-and-poet.

Report on the Census of Porto Rico, 1899. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1900.

The Biography. “Biography of Antonio Rafael Barcelo y Martnez (1868-1938.” https://thebiography.us/en/barcelo-y-martinez-antonio-rafael.

The National WII Museum. “World War II By The Numbers.” https://web.archive.org/web/20080106085848/http://www.nationalww2museum.org/education/education_numbers.html.

Velez Melendez, Edgardo. “The Puerto Rican Journey revisted: Politics and the study of Puerto Rican migration.” Centro Journal 7, no.2 (2005): 192-221.

Welcome to Puerto Rico! “Puerto Rico’s History.” http://www.topuertorico.org/history5.shtml.

Notes

[1] Registro Civil, 1805-2001, Puerto Rico, certificate of birth no. 665, (December 28 1891), Gerardo Antonio del Carmen Torres Diaz, oficinas del ciudad, Puerto Rico, https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:9Q97-YSDP-V1B?cc=1682798&wc=9PR5-K68%3A131388001%2C145785701.

[2] ”Politics and Reform in the Later Nineteenth Century,” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/puerto-rico-books-and-pamphlets/articles-and-essays/nineteenth-century-puerto-rico/politics-and-reform/.

[3] “Treaty of Paris of 1898,” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/rr/hispanic/1898/treaty.html.

[4] “Find A Grave Index,” database, Family Search, Sandalio Torres Monge, 1940, Carolina Municipality, Puerto Rico, Puerto Rico memorial (Registro Civil, 1805-2001, Puerto Rico, certificate of birth no. 665, (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QVPM-LKSY; U.S. Census of 1920, roll T625_2069, San Juan, Puerto Rico, e.d. 4, sheet 24, family 258, household of Gerardo Torres Diaz, https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&dbid=6061&h=59733455&tid=&pid=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=Jym516&_phstart=successSource.

[5] Antonio F. Castro, Decisiones de Puerto Rico: Compliacion de Sentencias Y Resolucciones Dictadas Por El Tribunal Supremo de Puerto Rico (San Juan: Law Library of Chicago, 1908), 42.

[6] Report on the Census of Porto Rico, 1899 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1900).

[7] U.S. Census of 1920, San Juan, Gerardo Torres Diaz household.

[8] Registro Civil, 1805-2001, Puerto Rico, Certifícate of birth no. 264, (November 6 1899), Maria Louisa Ortiz Sedano, oficinas del ciudad, Puerto Rico, Ancestry.com.

[9] Union de Puerto Rico donation receipt, a donation from Maria Louisa Torres, December 31, 1931, Box 1, Folder 9, Hunter College Centro Archives.

[10] Assembla General del Partido Liberal Puertorriqueño to Maria Louisa Torres-Ortiz, December 18, 1931, Box 1, Folder 9, HCCA.

[11] “Certificado de Inscripcion” no. 276 (July 5, 1917), Gerardo Torres ; Registro Civil, 1836-2001, Puerto Rico, certificate of marriage no. 369, (July 3 1918), Gerardo Torres and Maria Louisa Ortiz, Departamento de Saludo de Puerto Rico, Puerto Rico, Ancestry.com.

[12] Registro Civil, 1805-2001, Puerto Rico, certificate of birth no. 197, (June 8 1920), Gerardo Rafael Torres Ortiz, oficinas del ciudad, Puerto Rico, https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:9Q97-YSDF-7J5?cc=1682798&wc=9PRL-3TL%3A131388001%2C145903101.

[13] Ibid.

[14] U.S. Census of 1920, San Juan, Gerardo Torres Diaz household.

[15] Registro Civil, 1805-2001, Puerto Rico, certificate of birth no. 1269, (January 22 1930), Victor Manuel Simplicio Torres y Ortiz, oficinas del ciudad, Puerto Rico, https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:9Q97-YSDF-Y5W?cc=1682798&wc=9PR-T38%3A131388001%2C137952001.

[16] Registro Civil, 1805-2001, Puerto Rico, certificate of birth no. 385, (8 April 1930), Fabio Ortiz Torres, oficinas del ciudad, Puerto Rico, https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:9Q97-YSDN-ZB9?cc=1682798&wc=9PRG-MNL%3A131388001%2C146767501.

[17] Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, 1820-1957, list no. 6, arrivals September 18 1939, on ship Coamo from San Juan, Puerto Rico, line 3, Gerardo Torres, National Archives microfilm M237, roll 6400, https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&dbid=7488&h=1004600513&tid=&pid=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=Jym601&_phstart=successSource.

[18] U.S. Census of 1940, roll 2668, e.d. 31-1818, sheet 11B, family 244, Enrique Monge in household of Evie Hildebrand, https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&dbid=2442&h=5878888&tid=&pid=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=Jym609&_phstart=successSource.

[19] Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, 1820-1957, list no. 5, arrivals October 19, 1941, on ship San Jancito from San Juan, Puerto Rico, line 5, Gerardo Torres and family, National Archives microfilm M237, roll 6588 ; Korrol, Virginia, From Colonia to Community: The History of Puerto Ricans in New York City, 1917-1948 (Los Angeles, C.A.: Praeger 1983), 41.

[20] Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, 1813-1963, arrivals September 1, 1940, on ship Maiden Creek from Mayaguez, Puerto Rico, line 10-11, Gerardo Torres Ortiz and family, Ancestry.com.

[21] Provi Rosa (personal communication, January 20, 2004).

[22] Solsiree del Moral, Negotiating Empire: The Cultural Politics of Schools in Puerto Rico, 1898-1952 (Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2013), 54.

[23] Ibid.,54.

[24] Erin Blakemore, “The Brutal History of Anti-Latino Discrimination in America,” History, http://www.history.com/news/the-brutal-history-of-anti-latino-discrimination-in-america.

[25] Gerardo Torres-Ortiz Jr, to Gerardo Torres-Ortiz Sr., 1941, Box 1, Folder 7, HCCA.

[26] Joseph P. Fitzpatrick, “Attitudes of Puerto Ricans Toward Color,” The American Catholic Sociological Review 20, vol. 3 (Autumn 1959): 221.

[27] Ibid.

[28] U.S. Census of 1940, roll 4599, San Juan, Puerto Rico, e.d. 8-2, sheet 15B, family 337, household of Gerardo Torres Diaz, Ancestry.com.

[29] Victor Torres BIRLS Death File, U.S., Department of Veterans Affairs, 1850-2010 [database on-line], https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&dbid=2441&h=5903260&tid=&pid=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=Jym630&_phstart=successSource, ; De La Torres Associates, “Victor De la Torres Personal Biography”, HCCA.

[30] “World War II By The Numbers,” The National WII Museum: The War That Changed The World, https://web.archive.org/web/20080106085848/http://www.nationalww2museum.org/education/education_numbers.html.

[31] Manny Diaz. interview by Lillian Jimenez. Hunter College Centro, March 14, 2001.

[32] Alyssa Green, “Voices Oral History Project,” University of Texas Libraries, http://www.lib.utexas.edu/voces/template-stories-indiv.html?work_urn=urn%3Autlol%3Awwlatin.407&work_title=Rodriguez%2C+Alfonso.

[33] University of Alabama, August 8th, 1942, notice of Gerardo R. Torres student member election into Society of American Military Engineers, HCCA.

[34] U.S. Census of 1940, San Juan, Puerto Rico, Gerardo Torres Diaz household.

[35] Angel Canales. Lejos de ti. New York: Alegre Records, 1975.

[36]“An Introduction to New York City (NYC) Culture,” Baruch College, https://web.archive.org/web/20130505181316/http://www.baruch.cuny.edu/nycdata/culture/intro.htm.

[37] Nathan Glazer and Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Beyond the Melting Pot: The Negroes, Puerto Ricans, Jews, Italians, and Irish of New York City (Cambridge, M.A.: The MIT Press, 1970), 93.

[38] Virgina E. Korrol-Sanchez, From Colonia to Community: The History of Puerto Ricans in New York City, 1917-1948, (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1983), 39.

[39] Aldo Lauria Santiago and Lorrin Thomas. Rethinking the Struggle for Puerto Rican Rights: An American History. Manuscript.

[40] California Marriage Index, 1960-1985, Sutter, certificate of marriage, Gilbert Shine and Mary Louise Torres, California Department of Health Services, California, Ancestry.com.

[41] World War II draft registration card for Gerardo Torres, Box 1, Folder 1, HCCA.

[42] Deanna Boyd and Kendra Chen, “The History and Experience of African Americans in America’s Postal Service,” National Postal Museum, https://postalmuseum.si.edu/AfricanAmericanhistory/p8.html.

[43] “Adios A Los Vencedores,” El Imparcial, May 9 1945, HCCA.

[44] The Puerto-Rican Veterans Welfare Postal Workers Association Constitution and By-Laws, 1950, Box 1, Folder 1, HCCA.

[45] Edgardo Melendez Velez.” The Puerto Rican Journey revisited: Politics and the study of Puerto Rican migration.” Centro Journal 7, no. 2 (2005): 196.

[46] Henry L. Hunker, “The Problem of Puerto Rican Migrations to the United States,” Ohio Journal of Science 51, no. 6 (November 1951): 345.

[47] Juan Gonzalez, Harvest of Empire: A History of Latinos in America (Penguin, 2011), 87.

[48] Nathan Glazer and Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Beyond the Melting Pot, 100.

[49] California Federal Naturalization Records, 1843-1999, petition for naturalization, no.101819, petition of Maye Mabel Sanguinetti Torres, April 22, 1949, Ancestry.com.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Gerardo Torres Ortiz Jr. to Victor Torres Ortiz, June 28, 1951, Box 1, Folder 11, HCCA.

[52] Provi Rosa, personal correspondence.

[53] World Airlines ticket, February 25, 1955, Box 1, Folder 1, HCCA.

[54] Marilio Fontana to Gerardo Torres, March 21, 1955, Box 1, Folder 1, HCCA.

[55] Provi Rosa, personal correspondence.

[56] Gerardo Torres Jr. to Maria Louisa Torres, June 19, 1948, Box 1, Folder 11, HCCA.

[57] Mary Louise and Gilbert Shine wedding invitation, 1962, Box 1, Folder 8, HCCA ; Photographs Courtesy of Hunter College Centro Archives.

[58] Nitza C. Medina, “Rebellion in the Bay: California’s First Puerto Ricans,” Centro Journal 13, no. 1 (2001): 85.

[59] Gerardo Torres-Ortiz Jr., business card for Scotty’s Drive-In, HCCA.

[60] “Victor De la Torres Personal Biography,” HCCA.

[61] Victor Torres-Ortiz, handwritten list, HCCA.

[62] Mission District News, April 24, 1968, Box 3, HCCA.

[63] Ibid.

[64] Ibid.

[65] Ibid.

[66] U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, BIRLS Death File, 1850-2010, death record of Victor Torres, , Ancestry.com ; U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, BIRLS Death File, 1850-2010, death record of Fabio Torres, Ancestry.com ; U.S. Social Security Death Index, 1935-2014, death of Gerardo Rafael Torres, Ancestry.com.

[67] U.S. Veterans’ Gravesites, 1775-2006, cemetery address of Gerardo Torres,Ancestry.com ; U.S. Veterans’ Gravesites, 1775-2006, cemetery address of Fabio O Torres, Ancestry.com.

[68] Milton Marks to Maria Louisa Torres-Ortiz, June 9, 1975, Box 1, Folder 9, HCCA.

[69] Ibid.