Bridging Boricuas in the Constitution State: PRIDCO and Bridgeport, Connecticut Businesses in Puerto Rico, 1954-1992

Amanda Rivera

American Studies-Yale University

Embarking on the AGPR archival internship this summer, I wasn’t expecting to find connections to my specific region of interest, Connecticut. Roughly the size of Puerto Rico itself, the Constitution State is a bit of an oddball. The southernmost part of New England, Connecticut just barely qualifies as a part of New England, and its proximity to New York gives it a quasi-Mid-Atlantic feel. (Anecdotally speaking, I suspect New London County might be the dividing line between Yankees and Red Sox fans.) Likewise, in Puerto Rican Studies, Connecticut is a blip on many scholars’ radars. While academics have been decentralizing New York as the primary site of Puerto Rican diaspora in the last fifteen years or so (Mérida Rúa, Ana Ramos-Zayas and Mirelsie Velásquez in Chicago; Patricia Silver, Simone Delerme and Shantee Rosado in Orlando; etc.), Connecticut remains largely absent from social scientific literature. This is especially ironic, given the fact that, according to a recent CENTRO study, Connecticut has the 6th largest Puerto Rican diasporic population, and its capital, Hartford, has the densest Puerto Rican population of any city on the mainland. (Nashia Román, “Puerto Ricans in Connecticut, 2010-2016,” data sheet for CENTRO: the Center for Puerto Rican Studies, issued June 2018)

Embarking on the AGPR archival internship this summer, I wasn’t expecting to find connections to my specific region of interest, Connecticut. Roughly the size of Puerto Rico itself, the Constitution State is a bit of an oddball. The southernmost part of New England, Connecticut just barely qualifies as a part of New England, and its proximity to New York gives it a quasi-Mid-Atlantic feel. (Anecdotally speaking, I suspect New London County might be the dividing line between Yankees and Red Sox fans.) Likewise, in Puerto Rican Studies, Connecticut is a blip on many scholars’ radars. While academics have been decentralizing New York as the primary site of Puerto Rican diaspora in the last fifteen years or so (Mérida Rúa, Ana Ramos-Zayas and Mirelsie Velásquez in Chicago; Patricia Silver, Simone Delerme and Shantee Rosado in Orlando; etc.), Connecticut remains largely absent from social scientific literature. This is especially ironic, given the fact that, according to a recent CENTRO study, Connecticut has the 6th largest Puerto Rican diasporic population, and its capital, Hartford, has the densest Puerto Rican population of any city on the mainland. (Nashia Román, “Puerto Ricans in Connecticut, 2010-2016,” data sheet for CENTRO: the Center for Puerto Rican Studies, issued June 2018)

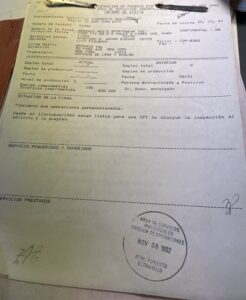

Imagine my surprise, then, when I stumbled upon multiple references – 9, in fact – to Connecticut as either the site of parent companies conducting business in Puerto Rico, or as an overall crucial site of commerce for the Puerto Rican businesses in the latter half of the 20th century. For example, the Universal Cigar Corporation of Gurabo, per a September 20, 1982 visiting form, mentions Connecticut as a site for their sourcing of raw material. Further, Jorge Saldaña, one of ten directors of Toa Alta Cement Company, took post-graduate courses at both the University of Connecticut and the Hartford College of Insurance.

The Valve Corporation: Complicating Racial Capitalism on La Isla del Encanto

The Valve Corporation of America, based in Bridgeport, Connecticut, began exploring the possibility of opening a plant in Caguas to make aerosol valves, under the leadership of an Emilio Morales, Chief Lab Technician of cosmetics and related products, in 1962. I want to emphasize the possibility that Morales was probably Puerto Rican himself. According to a 1962 visiting report, while Philip Sagarin appears to be the CEO of the Valve Corp. at this time, “it was decided to include the visit to Fomento in Mr. Morales’s vacation at the last minute.” Morales, who “has been in this type of business for the last 10-12 years and knows it from the ground up”, wanted “to return to Puerto Rico to live there” and was “confident that in the event that Mr. Sagarin decided to establish a manufacturing plant in Puerto Rico he (Mr. Morales) would be qualified to manage the operation.”

The Valve Corporation of America, based in Bridgeport, Connecticut, began exploring the possibility of opening a plant in Caguas to make aerosol valves, under the leadership of an Emilio Morales, Chief Lab Technician of cosmetics and related products, in 1962. I want to emphasize the possibility that Morales was probably Puerto Rican himself. According to a 1962 visiting report, while Philip Sagarin appears to be the CEO of the Valve Corp. at this time, “it was decided to include the visit to Fomento in Mr. Morales’s vacation at the last minute.” Morales, who “has been in this type of business for the last 10-12 years and knows it from the ground up”, wanted “to return to Puerto Rico to live there” and was “confident that in the event that Mr. Sagarin decided to establish a manufacturing plant in Puerto Rico he (Mr. Morales) would be qualified to manage the operation.”

I would like to underscore a few things. First, Morales’s travel to and from Puerto Rico, assuming he’s Puerto Rican, underscores the fluidity of Puerto Rican migration between the mainland and the island, as many scholars have noted (Jorge Duany, for example, in the Puerto Rican Nation on the Move). Second, and rather crucially, Puerto Ricans were hardly passive participants in the racial capitalist project of PRIDCO. Morales not only participated in the exploration of Puerto Rico as a new site of enterprise for the Valve Corp. – he was instrumental in utilizing the Caribbean tax haven, demonstrated in Sagarin’s ultimate application for exemption in 1965. This complicates the traditional narrative of Puerto Rico’s history of racialized economic exploitation. Much like Ismael Garcia-Colón demonstrates in his most recent work Colonial Migrants at the Heart of Empire: Puerto Rican Workers and U.S. Farms (2020), Puerto Ricans likewise shaped the very policies meant to marginalize them.

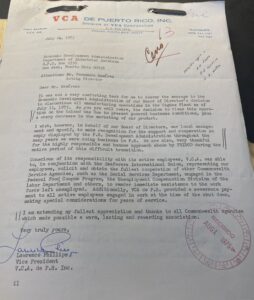

By 1966, after the purchase of the operations of Shaw Harrison Corporation, Custom Molders of P.R., Inc., and Caguas Plastics, the Valve Corp. plant in Caguas had opened, albeit unsuccessfully. Per a July 24, 1975 letter from “V.C.A. de P.R., Inc.” vice president Lawrence Phillips, to acting director Fernando Ramírez, by July 11, 1975, the decision was made “to discontinue all manufacturing operations in the Caguas Plant” and give social assistance and severance to “all active employees engaged in work at the time of the shut down”.

Warnaco Inc. and Weaving the Threads of Business Acquisitions

Finally, Warnaco, Inc. has a bit of a convoluted story. Per the (confusing) paper trail, what became known as Warnaco appears to have started off as three separate businesses, all located in Aguas Buenas: Alto Knitting Mills, Superior Knitting Mills, and Insular Dye Works. As of May 1954, all three businesses made clothing or textile-related products. Alto Knitting Mills and Insular Dye Works were owned by the Landau Knitting Corporation, based out of Keyport, New Jersey. While not explicitly stated, since Superior Knitting Mills was listed in 1971 as a part of the Puritan Sportswear Corporation, it can be assumed that when Puritan, based out of Altoona, Pennsylvania, bought out Alto Mills in January 1962, Puritan acquired Superior Knitting Mills and Insular Dye Works, too. Sweaters were the main product manufactured at this time.

Finally, Warnaco, Inc. has a bit of a convoluted story. Per the (confusing) paper trail, what became known as Warnaco appears to have started off as three separate businesses, all located in Aguas Buenas: Alto Knitting Mills, Superior Knitting Mills, and Insular Dye Works. As of May 1954, all three businesses made clothing or textile-related products. Alto Knitting Mills and Insular Dye Works were owned by the Landau Knitting Corporation, based out of Keyport, New Jersey. While not explicitly stated, since Superior Knitting Mills was listed in 1971 as a part of the Puritan Sportswear Corporation, it can be assumed that when Puritan, based out of Altoona, Pennsylvania, bought out Alto Mills in January 1962, Puritan acquired Superior Knitting Mills and Insular Dye Works, too. Sweaters were the main product manufactured at this time.

In 1965, Puritan was bought out by Warner Brothers (not the film company), and the company was seeking to expand operations in Cidra. Products and locations shifted – the acquiring of a sportswear factory in 1960s Guaynabo saw an opportunity to make bras, before ultimately closing in 1972. Further, the 1970s saw the expansion of Warner Brothers, now called Warnaco Men’s Sportswear, throughout Puerto Rico, with factories not only in Aguas Buenas and Cidra, but also Comerío and Carolina. Per Warnaco’s 1976 annual report however, “Warnaco had a very bad year in 1976.” Warnaco Men’s Sportswear, specifically, were put in a “second group” of concern for Warnaco – not exactly on the chopping block, but requiring “major changes in management, merchandising, and facilities” to “bring substantial improvement”. While the company appeared to maintain its factories in Cidra and Aguas Buenas through the 1980s, Warnaco Inc. officially ended its Puerto Rican operations in 1992.

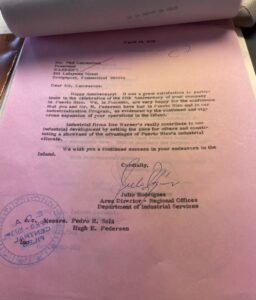

As tricky as it was navigating this complicated tale of shifting ownership and expansion, the relationship between Fomento and this Bridgeport enterprise was mutually enjoyed. A letter dated March 23, 1973, from Julio Rodríguez, Area Director – Regional Offices of the Department of Industrial Services (Fomento) to Mr. Phil Lamearoux, President of Warner’s in Bridgeport, celebrates the company’s 20th anniversary in Puerto Rico. Rodríguez writes, “Industrial firms like Warner’s really contribute to our industrial development by setting the pace for others and constituting a showcase of the advantages of Puerto Rico’s industrial climate.” Little did Rodríguez know that roughly 20 years after this letter, Warnaco’s abandonment of Puerto Rican operations would play a part in the devastation of Puerto Rico’s economy, throughout the end of the 20th century and well into the 21st.

Conclusion

As I write this, I have returned to New Haven to begin my third year of graduate studies, in which, among many tasks, I will be writing my dissertation proposal. In doing so, I want to keep in mind these important, albeit understudied, connections between Connecticut and Puerto Rico. In my anticipated fieldwork, I will carry these reflections with me to develop my understanding of the nuances of puertorriquenidad in the Constitution State.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.