Migration, Community, Labor and Civil Rights: Puerto Rico’s Department of Labor in New York-The Migration Division, 1945-1968

Aldo Lauria Santiago

The arrival of large numbers of Puerto Rican migrants in New York towards the end of World War II led to efforts by public and private agencies to help migrants and communities manage problems with jobs, housing, welfare, social services, education, language, and other needs. The opening of the Migration Division-the office of Puerto Rico’s Department of Labor in the US–was a product of both the realities and perceptions of the “crisis” of 1947, in which the Puerto Rican migrant community received a surge of “bad press” from right-wing media outlets at the same time as migration surged to unprecedented numbers.

The purpose of the Migration Division was to manage the expectations, rights, and needs of migrants who considered themselves citizens of two nations. The Division office played the role of a consulate of sorts that worked both to facilitate and legitimize the US citizenship rights of Puerto Rican migrants, as much as to maintain and support the economic, cultural, and ethnic coherence of Puerto Ricans as a national origin identity. A hybrid institution, the Migration Division was simultaneously an agency of the Puerto Rican Labor Department and also became a civil rights, labor, and community organization with organic ties to most Puerto Rican political and social organizing efforts through the 1960s. It was established by the Puerto Rican Legislature, Governor Pinero, Labor Secretary Sierra Berdecia and former Socialist Party leader and Director of the UPR Social Science Center, Clarence Senior. Senior became its first national director during the 1947 “crisis,” in which the discovery by New York’s right-wing press of the many thousands of recent Puerto Rican immigrants created a thunderstorm of rejection and “bad press” for the growing Puerto Rican community.

The Migration Division was not unprecedented. Puerto Rico’s Washington Office and Commerce Department had run an employment office in Harlem and an identification office (that provided official ID’s to migrants) through the early 1940s. There was also legislation in Puerto Rico since 1918 that allowed the insular government to intervene in the labor contracting of Puerto Ricans on the island, as well as extensive experience with labor recruitment and contracting during World War II through the Federal War Manpower Commission and the US Employment Service. These efforts were updated with Law #25 of 1947 that established the Migration Bureau within Puerto Rico’s Labor Department.

Community leaders in New York City had been demanding the creation of this sort of support office as soon as the war ended, with the knowledge that a similar office had existed over a decade earlier. The principal civil rights and community organization of the mid-1940s, the Spanish American Youth Bureau (SAYB) led by Ruperto Ruiz, had organized a major campaign with Puerto Rico’s government in support of a multi-service center paid and sponsored by the Puerto Rican government to help the migrants with their adjustment.[1] Left and labor leaders in New York also supported the office opening [2]. The leaders of the principal Puerto Rican civil rights organization of that period, the Youth Bureau had led the response of the NYC Welfare Council. It continued to play a role in the process as allies of the Migration Division after it was established.

Pressure from the political and labor context of 1946-1947 spurred the PPD leaders in Puerto Rico to open the Migration Division. The attacks on the migrants by the right and the increased demand for New York’s social service, welfare, and housing infrastructure encouraged Governor Piñero and his labor commissioner to open the office. Needless to say, the larger context was the pressure created by the surge of self-managed and self-financed migration from Puerto Rico. The scale and rapidity of this migration took officials by surprise and island government officials felt compelled to respond.

Pressure from the political and labor context of 1946-1947 spurred the PPD leaders in Puerto Rico to open the Migration Division. The attacks on the migrants by the right and the increased demand for New York’s social service, welfare, and housing infrastructure encouraged Governor Piñero and his labor commissioner to open the office. Needless to say, the larger context was the pressure created by the surge of self-managed and self-financed migration from Puerto Rico. The scale and rapidity of this migration took officials by surprise and island government officials felt compelled to respond.

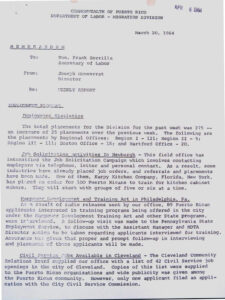

The Migration Division began in New York City, but later opened offices or hired coordinators in various sites with a growing Puerto Rican presence like Chicago. National Director Clarence Senior (former Director of the Social Science Research Center at the UPR and Socialist Party leader) coordinated work with city agencies and organizations and established an employment referral office for migrants already in New York. The Division also managed the “Insular” Labor Department’s first big progam: replacing privately contracted seasonal farm workers with a government-sponsored contract and seasonal labor program. This work lasted through the 1970s and included negotiating and enforcing the terms of the farm worker contracts, implementing insurance, and assisting with the myriad problems faced by dispersed farmworkers brought to work in the Northeast. During the 1950s, the Division quickly expanded to include public relations, education, and community organizing. By 1959, its annual budget, paid for by the insular Department of Labor, had reached one million dollars (about nine million in today’s dollars) with dozens of employees and multiple sections.[3]

The public relations office managed the public image of Puerto Ricans in New York and responded to the attacks on the migration. The education office worked with the Department of Education, while the welfare office worked with New York’s complex public and private social services infrastructure. The community organizing section worked with local communities in the entire region helping them respond to crises or organize permanent committees. Some of the leading activists and professionals served in these offices, including Eddie Gonzalez, Juan Jose Osuna, Leonard Covello, Allan Perl, and others.

The first New York office director was Manual Cabranes, followed by Jose/Joe Monserrat; both were second-generation Puerto Ricans and trained as social workers in New York’s immigrant settlement houses.

The office developed a hybrid style that combined a consular component with the projection of the welfare state goals of a colonial government undergoing rapid transformation. Leaders of the Popular Democratic Party in Puerto Rico tried to make sure that the MD appeared to be political even though it was formally a branch of the government of Puerto Rico in New York. In the moments of the crassest sort of political interventions by the PPD in New York (the campaign by PPD authorities against American Labor Party leader Vito Marcantonio in 1949 and 1950) they kept the office out of the campaign even as its director (Cabranes) quietly facilitated information to Munoz Marin and others in Puerto Rico.

The Migration Division helped manage the expectations, rights, and needs of migrants who considered themselves citizens of two nations. In this sense, the MD played the role of a consulate of sorts that worked both to facilitate and legitimize the US citizenship rights of Puerto Rican migrants and maintain and support the cultural and ethnic coherence of Puerto Ricans as a minority. By the mid-1950s, anyone involved in work involving community services, welfare, and work issues involving Puerto Ricans could recognize what labor journalist Mitchel Levitas stated in his New York Post articles: the Migration Division “is irreplaceable in helping the immigrants meet the multitude of strange and frightening problems in a land that is legally their own but which is foreign almost every other way.”[4]

Once Clarence Senior became National Director in 1951, he worked aggressively with the labor unions to make them responsive to their growing Puerto Rican membership. For Senior and New York City office director Josesph (Jose) Monserrat, unions were fundamental pillars of American society; in Senior’s own words, “unions are one of the most important single institutions to help the speeding up of the adjustment process for Puerto Ricans.” He opposed restrictions on unions, including the Taft Harley law and further measures proposed in Congress during the late 1950s.[5] The Migration Division refused to refer workers to worksites on strike and preferred unionized shops, steering workers away from worksites with the most complaints.

The Migration Division’s employment section monitored jobs and wages in New York’s economy and pushed local employment services (including the critical Federal USES) to hire Puerto Ricans. Soon, the work expanded to include communication with the unions that organized the worksites to which the office’s clients were referred. The office was extremely sensitive to the condition of working-class immigrants and their need to integrate with working-class organizations. The MD employment section learned a lot about corrupt or unresponsive unions through the claims and complaints of workers against union officials. A 1952 complaint by young Puerto Rican workers at an ILGWU Local 91 garment shop led to an investigation by the Federal Department of Labor Wages and Hours division.[6] A similar complaint arrived in November 1953 from Carmen Cuesta and 30 Puerto Rican garment workers at Joan Douglass Underwear. They were not happy with Local 62 of ILGWU and reported they made about $30/week and not paid their overtime. After the intervention of Migration Division officials and other allies, the leader of the complaint, Laura Maldonado, had been elected assistant Chair Lady and the workers were offered 10% raises.[7]

The Migration Division quickly began a dialog with the many unions representing workers in the factories, restaurants, laundries and hotels that placed the work orders. These early efforts included internal work contacting union leaders, referring worker complaints, and providing translations. It also extended to meetings with workers and union officials facilitated by Migration Division staff. In 1952, Teamsters Local 819 asked the MD for help in convincing workers at Arrow Novelty Shop that it was in their best interest to vote for the union. Shop chairmen Israel Garcia and Hernan Santiago tried to convince the workers to keep the union but failed. In this case, there was little the Migration Division staff could do.[8] All of this work expanded during 1957 when MD officials noted “a considerable increase in union requests for various kinds of assistance.”[9]

Eventually the labor organizations learned to rely on the Migration Division, as labor organizers found that increasingly their workers were Puerto Rican. By the 1950s, the Migration Division had become experts at leveraging allies and relationships within the labor movement could count on the leadership of Puerto Rican (and other Latino) shop-floor leaders in dozens of unions who were now exercising their own pressure for changes from within the unions. By 1960, the list of Hispanic, mostly Puerto Rican (full-time) trade unionists had grown to at least 400.[10]

As a result of this sort of work, the Migration Division staff was part of the process of convergence of labor leaders, civil rights fights and public officials who monitored and responded to complaints and crises at workplaces. Because of their daily contact with thousands of Puerto Ricans, the MD served as a clearinghouse of complaints and support requests in both directions, from the workers, and organizations. One of the first strong early relationships was with the Spanish Affairs Committee of District 65 and with the Hotel Workers Union Local 6. By the late 1950s nearly every union local had at least a few Puerto Rican organizers and staff members, creating a network of a few dozen full-time organizers (backed up by hundreds of Puerto Ricans serving as work-site union representatives) who converged at the Migration Division and the Central Labor Council.

The Migration Division also pressed the National Labor Relations Board in 1957 to hire Spanish-speaking investigators, a fact that reflected both their level of involvement and the political authority they began to have. MD officials complained internally that they had been doing the work on a weekly basis, fighting workers’ layoffs for union activity.[11] Indeed, whenever the NLRB needed support with the dozens of certification and decertification votes that were filed during the 1950s, they came to the MD to translate or assist in the meetings. In May 1953, for example, MD staff translated materials for an upcoming election at House Beautiful Curtains, Inc.[12]

The MD also played a leading role in training workers in labor relations and labor organizing. In a confidential assessment by employment section staff, Cardona and Gonzalez 1960 of the MD “Industrial Relations Orientation Program” assessed the needs and role that they would have to play as allies in the fight for economic improvement and unionization of Puerto Rican workers.[13] In April 1962, Gonzalez of the MD, with Edward Grey from the UAW and with support from Rutgers University, organized a six-week training program in Spanish for emerging labor leaders in NY and NJ. The office also facilitated regular training sessions for emerging labor leaders. In April 1963, the office ran a training program for the United Shoe Workers of America, with a 65% Puerto Rican membership, training 25 men and women as shop stewards and board members.[14]

The Migration Division connected their “labor” work with their larger community work. While organizational forms were different, MD officials knew that when representatives of the dozens of local organizations that formed part of the large Consejo de Organizaciones Hispanas (COH), which the MD coordinated and Monserrat directed, went home, they joined the very same workers and union members involved in the fights over wages and working conditions. In 1961 the labor office staff at the MD chastised a COH leader for representing misleading ideas about how a major union allowed only for the minimum wage without recognizing the work that had been done in the past few years, reminding leaders that a great number of the COH’s own membership belonged to unions.[15] Other contacts were more positive. The MD was asked to send a translator to one small factory to help explain to the 35 Spanish-speaking women who had just signed the cards in support of the union the outcome of the negotiations with the employer and the terms of the new contract.[16] Throughout the early work of the MD with Puerto Rican workers the complaints were repetitive: unresponsive officials, low wages, shifting job descriptions, rejected claims for benefits, firings, unpaid overtime.

By the early 1960s, as the community had matured and second-generation ethnic Puerto Ricans (born in the US) developed a rich set of relations with the migrant community, the role and character of the Migration Division became more complex as it dialogued with the Black Power and the civil rights movements of those years. By 1960, Monserrat had established himself and the office as a coordinator of all sorts of community development and protest efforts and became a civil rights leader in his own right. By then, the Migration Division had formed the most important umbrella of civil organizations in New York, the Spanish American Council and local councils in each borough (and in many other cities outside of New York). Monserrat himself played a critical role in the labor and rights mobilizations of the early 1960s, including the hospital workers’ strike, the demands for high-skill/high-pay jobs, the 1964 school boycott, Puerto Rican participation in the March on Washington, and many other campaigns.

Audio PlayerInterview with Eddie Gonzalez, Center for Puerto Rican Studies

Footnotes

[1] Ruperto Ruiz, President, Spanish American Youth Bureau to Luis Munoz Marin, 15 December 1946; Ruperto Ruiz to Luis Munoz Marin, Luis Munoz Marin Papers, Fundacion Luis Munoz Marin; Thomas, Lorrin. Puerto Rican Citizen: History and Political Identity in Twentieth-Century New York City. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

[2] Bernardo Vega to Luis Munoz Marin, #17, Sub-Serie 13.1-13.3, Serie 8, Seccion IV, Luis Munoz Marin Papers, Fundacion Luis Munoz Marin; Jesus Colon also expressed support for an island-run office that would aid the migrants. The editors of Liberacion, the newspaper of the Puerto Rican-led Hispanic section of the Communist Party expected Sierra Berdecia to help take more vigorous action against the jobs racket, employment agencies that took advantage of recent migrants (Liberacion, 20 March 1948).

[3] “Helping the Puerto Ricans help themselves,” Mayors Papers, Box 276, Folder 3217, Roll 149, La Guardia and Wagner Archive, La Guardia Community College.

[4] Published a series of articles on the New York labor movement and Puerto Ricans. Mitchel Levitas. New York Post, 15 July 1957.

[5} Memo, CS to Offices, Restrictive Labor laws, 19 May 1958, Box 2947 Folder 3, OGPRUS, Centro Archive; Clarence Senior to Jack Wieselberg, International President & Norman Zultkowsky, General Secretary Treasurer International Handbag, Luggage, Belt and Novelty Workers Union, 17 September 1952, Box 2045, Folder 38, OGPRUS, Centro Archive. Alan Perl played an important role in all major negotiations of programs and relationships developed by the Migration Division.

[6] Bou to Montserrat, 10 December 1952, Box 2045, Folder 46, OGPRUS, Centro Archive.

[7] Bou to File, 16 December 1953, Box 2993, Folder 14, OGPRUS, Centro Archive.

[8] Memo, 21 November 1952; Bou to Ruiz, 24 November 1952; Ruiz to Bou, Box 2056, Folder 9, OGPRUS, Centro Archive.

[9] Weekly Report, Clarence Senior to BL, 9 October 1957, Box 2948, Folder 6, OGPRUS, Centro Archive.

[10] Michael Luis Ristorucci. “Some observations on the Hispanic labor committee, the labor movement, and post-World War II Latino labor activism in the metropolitan New York area.” Harry Van Arsdale Junior Memorial Foundation, 2002.

[11] Weekly Report, Clarence Senior to BL, 9 October 1957; Box 2948, Folder 6, OGPRUS, Centro Archive.

[12] B. Selden, Election Department, NLRB, to Virginia Maldonado, 17 November 1953, Box 3005, Folder 3, OGPRUS, Centro Archive.

[13] See for example: Industrial relations memo/training program, 5 November 1962, Box 2855, Folder 14, OGPRUS, Centro Archive; Edward Gonzalez, to Louis Cardona, Box 2855, Folder 14, OGPRUS, Centro Archive.

[14] Edward González to Ralph Rosas, Weekly Report, 30 April 1963, Box 2057, Folder 4, OGPRUS, Centro Archive.

[15] Memo, L. Cardona to Ralph Rosas, 8 November 1961, Box 2559, OGPRUS, Centro Archive.

[16] Ruiz to Bou, 7 August 1952 , Box 2033, Folder 20, OGPRUS, Centro Archive.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.