An Interview with Stuart Ross

By: Jackson Dilullo

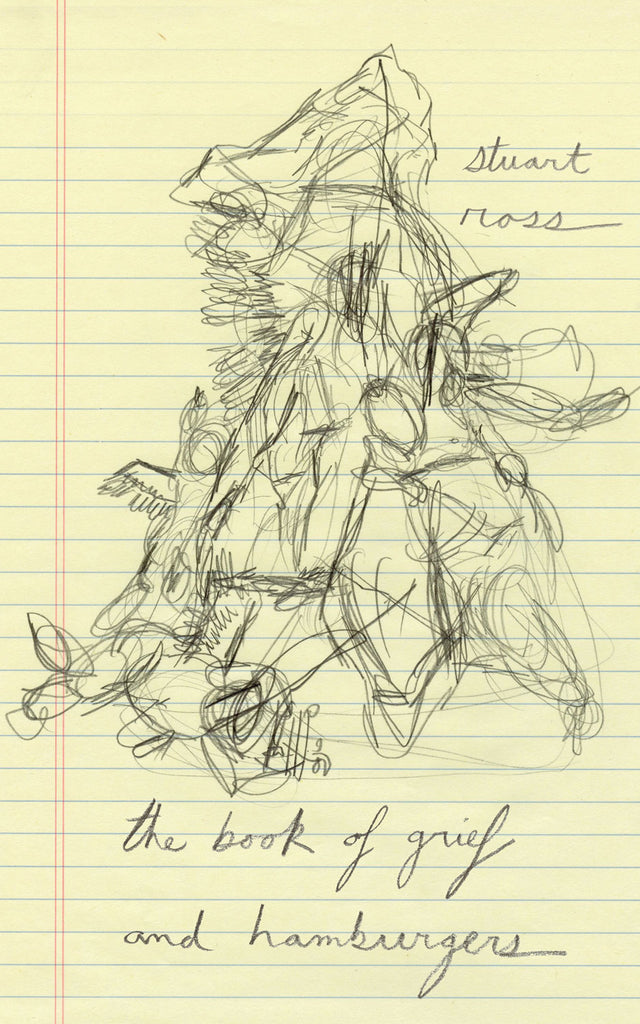

Stuart Ross is a Coburg, Ontario-based writer, editor, educator and poet who has published 12 poetry collections and five novels, and has had his work translated to dozens of languages. His most recent publication, The Book of Grief and Hamburgers, won the 2023 Trillium Book Award and was described as ‘a moving act of resistance against self-annihilation.’ Others won the 2017 Canadian Jewish Literary Award for Poetry and the 2010 ReLit Award for Short Fiction. He recently worked as a faculty member at the Banff Center for Arts and Creativity, and frequently gives lectures and readings across Europe and the Americas. According to the Writers’ Union of Canada, he will even give a reading in your living room.

Ross wrote his first poems at just ‘eight or nine years old,’ and was inspired by the likes of E.E. Cummings, Emily Dickinson, and David McFadden. Ross’ soon-to-be newest publication The Sky is a Sky in the Sky, is the culmination of decades of inspiration. Ross’ love of writing shines in every inch of The Sky is a Sky, and his surrealist influences drive themes of both joy and despair, isolation and community; family and sacrifice. This collection will be available for purchase online on September 10th, 2024.

JD: In an interview with Poetry in Voice you said you ‘revel in exploring the possibilities of language and form,’ which shines in The Sky is a Sky. I’ve noticed in some of the early poems, many characters read or hear dialogue within the confines of a poem. In The Sky is a Sky in the Sky, you write; “…Our skin / acts as a protective wrapper, Jack says. And: Lovely weather / we’re having.” Later, in Fireball XL5 Aubade you write:

The air is sucked from my cabin, and

as I lie dying, I hear my mother cry,

O Absalom my son, O Steve Zodiac,

O Stuart, O Zalman Nehemiah, O Seth,

and I shrink into her warm arms

that no longer live, and yet still she is my mother.

How does hearing or reading this information, as opposed to interpreting it or being told it by the speaker, enhance or accentuate your poetry? How significant are these interactions to the themes of these poems?

SR: Most of what I do in my poetry isn’t really conscious — it’s more intuitive, a matter of chasing along wherever the poem seems to be going. In that way, I’m not concerned about themes; my goal isn’t to explore a theme or inflict a theme. And even if it was, I wouldn’t expect readers to necessarily see the themes in a poem that I might see. I think, really, as a reader, you are better able to answer the questions in your last paragraph. But I’ll say this: It’s possible that various speakers enter into my poems because I find it exciting for new kinds of sentences, new kinds of sensibilities to interrupt my poems and perhaps steer them in new directions.

But I’ll be specific here: my mother, who died in 1995, used to kind of dramatically say to me, “Oh Absalom, my son.” I just looked up that quote and see that it is King David from the Old Testament lamenting the death of his third son. That’s interesting, because, in fact, I was my mother’s third son. How add that she would recite this line of grief! Anyway, I seem to be overlapping the Biblical Absalom with the animated TV character Steve Zodiac from a show I watched as a child, and then me (Stuart), and then my Hebrew name (Zalman Nehemiah), and then Seth, which was what my mother would have named me had her own mother been able to pronounce the “th” sound. Seth, incidentally, was the third son of Adam and Eve. I didn’t realize all of these third-son coincidences until this moment. Which reinforces for me the belief that the most exciting things in poetry happen unconsciously, or by chance.

Oh, and as to Jack Teagarden, the legendary trombone player of the 1930s and 1940s, I don’t know why he wandered into my poem, except that I know that Charles North, who inspired the poem, is a big jazz fan, like many other New York poets of his generation. Both of those bits of dialogue I attribute to Teagarden are, of course, imaginary, and they are exactly unlike anything I would have expected the actual Jack Teagarden to say. I like juxtapositions like that.

JD: Based upon that interview, it’s easy to assume you’re someone who loves their work. Which is why another early poem in , Valediction, surprised me. Serving as a ‘final bow’ of sorts, it felt too short for a writer as passionate as yourself. You imply, however, that your writing holds a deeper, undiscoverable personal significance:

All that will

be left of me:

in the margins of books

pencilled murmurs

you will never

decipher.

It appears writing is an intimate exercise for you. In what ways do you write for yourself, and in which ways do you write for your readers?

SR: I love the metaphor you have read into this poem. I think the poem came from the fact that my grandfather, in hospital in his last days, was unable to speak but wrote some indecipherable Hebrew on a piece of paper towel, and those unreadable words are the words he left behind. I imagined someone trying to learn something about someone who’s died by looking at the notes they pencil-scrawled in the margins of books but being unable to read them. We want so much to know what the dead thought, but we can never know. That just occurs to me now as a possible explanation for the poem. Also, I never write in the margins of books myself.

Now, to your question! I mostly write for myself and hope that there are readers out there who will dig what I’m writing. Or at least find it interesting. Or offensive. Or worth thinking about for a few moments. One thing I consciously do is try not to pander to readers, and I put a stop to it if I catch myself doing it. That’s a terrible tunnel to fall into. I want to be free to experiment, and hopefully my readers will come along for the ride.

JD: You’re a poet with many influences, telling Touch the Donkey that ‘Charles North’s The Nearness of the Way You Look Tonight and Ron Padgett’s Toujours l’Amour are very important to [you].’ At the conclusion of the first section, The Sky, you pen a poem dedicated to the two poets titled Life Begins When You Begin the Beguine. Is honoring the legacies of your inspirations something you prioritize in your writing? If so, how does Life Begins work towards that goal?

You are absolutely right, I drink in many influences. I am so grateful to the poets who have written work that excites me, that shakes up poetry, that shows me ways of doing things I’ve never thought of, so yes: Charles and Ron, Renee Gladman, Larry Fagin, Lisa Fishman, Emily Pettit, Dave McFadden, Sawako Nakayasu, Nelson Ball, Lisa Jarnot, Nicanor Parra, Tom Clark… I want to be in conversation with them, I want to pay homage to them, I want to turn other people on to their writing. So I don’t exactly prioritize them: they often spark my poems, and I acknowledge them out of respect, and because it’s the right thing to do if I’m ripping them off in some way! “Life Begins When You Begin the Beguine” — that title is a blend of two jazz standards: “Life Begins When You’re in Love” and “Begin the Beguine.” That was an homage to the Charles North poem “The Nearness of the Way You Look Tonight,” whose title presumably comes from the jazz standards “The Nearness of You” and “The Way You Look Tonight.” On a basic level, I loved the challenge of coming up with two jazz titles I could blend together. But it’s not a goal for me to honour the legacies of the poets I admire. It’s just something that happens along the way.

SR: Circling back to the importance of form within your poetry, what is the significance of The Sky is a Sky in the Sky’s three distinct sections? What went into the organization or selection process for each, and how much were each poem’s content and form considered during that process?

I hope to not disappoint you, but very little thought went into the organization of that book’s structure. I had about 120 pages of poems, and my editor suggested I break it into parts, maybe to give readers a different experience, maybe just to break it up. I had done that with a few of my earlier poetry books, so I was game. I was going to just title each section “I,” “II,” and “III,” but my editor at Coach House Books, Nasser Hussain, suggested breaking up the book’s title to title the three sections. Once that was a done deal, I tinkered with the order, kind of seeing each section as a side of an album: how do I want to start each side of the album, how do I want to finish it? How do I vary the “tracks” in between the beginning and end? How could I create echoes within each section (for example, at least one long poem in each section, and at least one Razovsky or Blatt poem in each section), to give the book a kind of throughline, and how could I simultaneously, make each section a unique experience for the reader.

My last poetry book, incidentally, was broken into five sections. My publisher had asked me to write some copy for the catalogue about the book (Motel of the Opposable Thumbs) and I jokingly wrote that I was structuring it after a Béla Bartók’s String Quartet No. 4. I knew practically nothing about Bartók, except that he was a very daring classical composer. But then it started appearing on the internet — that my book was structured after String Quartet No. 4. So I found the piece of music on YouTube and listened to it. It was divided into five movements, and I found the first, third, and fifth movement melodic and pleasant to listen to, and the second and fourth movements more discordant, more avant-garde. So I put all my most accessible, conventional poems (when I refer to any of my poems as conventional, I think they’re still pretty weird by mainstream standards, if you can refer to a “mainstream” in poetry) in parts one, three, and five, and the really weird-ass, often incomprehensible poems in sections two and four. Voilà! I had emulated Bartók in a very forced way.

JD: In the book’s final entry, simply titled Poem, you write: “I see a light / at the end / of the tunnel / and beyond that / a tunnel.” Within the greater context of section three, In the Sky, it’s a sharp contrast from the extended prose we see in other selections. I can’t help but think back on Valediction. It’s in a similar vein in both its tone and length, and begs the question; Have you considered the possibility of finishing? Is that ‘light at the end of the tunnel’ the prospect of sharing more of your experiences with the world, or rather, a metaphorical step away from the world of publication?

SR: I don’t write metaphorically, at least not consciously. So I’m always interested when readers find these kinds of things in my poem. Makes me feel smarter than I actually am. I like your connection between those two short poems. I do love good minimalist poems, like those by the aforementioned Ball and Fishman, as well as Lorine Niedecker, Michael O’Brien, John Phillips, and others. My own minimalist poems are rarely stand-alone, but usually part of a sequence, such as “Racter in the Forest” and “Ten” from The Sky Is a Sky in the Sky. Now, on to your question…

I’m not sure what you mean by “finishing.” Your interpretation of the poem is interesting, and I think it’s totally legit. But “the light at the end of the tunnel” — that means that when things are going crappy, there’s some hope again. I was also thinking of people who have had near-death experiences and report having seen a glowing light.… Anyway, in my sad-sack outlook, that positive ray of light is going to be eclipsed by yet another goddamn tunnel. I’m such an optimist!

Thanks for these great questions, Jackson. I enjoyed the workout!

Jackson Dilullo studies sports journalism, with a minor in creative writing.