FAQ

More FAQ is coming soon. Write to me if you have any questions you’d like answered. –Brad

-

Henri Pille, cover illustration for Le Chat Noir, the magazine started in 1882 by Rodolph Salis for his cabaret of the same name. An ephemeral bibelot is the name given to any of the hundreds of little art magazines published around the world in the 1890s. The most influential of these, Le Chat Noir, began publication in Paris in 1882. It was the house organ of the famous cabaret of the same name, a celebrated gathering place for the revolutionary spirit of Modern art. For a time, it seems as though any young bohemian passing through Paris would go home and start their own little magazine modeled on Le Chat Noir. Similar little magazines can be traced throughout Europe, Russia, Japan, India, and the Americas. In the English speaking world, the most famous were the Yellow Book and the Chap-Book, but their renown makes them atypical. Most of them had very limited distribution and were quickly forgotten. Together, however, they made up one of the first artistic fads of Modernism.

In the United States, the fad was at its peak from 1894 to 1898, when hundreds of ephemeral bibelots were published across the country, from metropolitan centers to small towns in the midwest. The ephemeral bibelots were beautifully illustrated in the Aesthetic Arts style. They provided an outlet for frank and queer treatments of sex and sexuality, the development of nonsense poetry, proto-Dadaist and proto-Surrealist parodies, and a free interplay between literature and the graphic arts. These trends explain the prominence of black cats and butterflies on their pages: these were internationally recognizable icons of sexual and artistic provocation.

Although presaging many of the forms that came to be known under the rubric of Modernism, the bibelots are distinct from the more well-known “modernist little magazines” that got their start in the 1910s. Indeed, editors of these later modernist little magazines did everything they could to bury the bibelot movement. And succeeded. Since then, the bibelots have been largely overlooked even by the major academic chroniclers of the periodicals, scoring scant mention in Frank Luther Mott’s magisterial history of American magazines and being dismissed outright in the classic work on Modernist little magazines by Hoffman, Allen, and Ulrich, who simply wrote that they “were not very inspiring.”

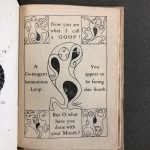

Gelett Burgess, “The Goop (Verse and Cartoon),” the Lark No. 22, February 1897. America’s most important bibelot editor, Gelett Burgess, summed up the movement in 1897 when bringing his little magazine, the Lark, to a close after just two years. Even then preternaturally inclined to self-dismissal, Burgess officially declared “the freak fleet” of which he was the commodore disarmed:

“Suddenly, without warning, the storm broke, and a flood of miniature periodicals began to pour over the land. The success of the “Chap Book” incited the little riot of Decadence, and there was a craze for odd sizes and shapes, freak illustrations, wide margins, uncut pages, Jenson types, scurrilous abuse and petty jealousies, impossible prose and doggerel rhyme. . . . It was a wild, hap-hazard exploration in search of a short cut to Fame; it proposed to carry Prestige by storm.

“But the war is almost over now, and the little wasp-like privateers that have swarmed the seas of Journalism are nearly all silenced; the freak fleet has disarmed, but who knows how many are missing?”

-

I use the term relational aesthetics to refer to the highly self-reflexive artistic mode of the ephemeral bibelots. The idea is to emphasize not the art object but the relations it evokes. The frisson of relational aesthetics comes from the redistribution and cross-referencing of particular optic and linguistic cues, for instance black cats and butterflies. It implies circulation and network dynamics.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres – Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), 1991, Candies individually wrapped in multicolor cellophane, endless supply. Dimensions vary with installation; ideal weight 175 lbs. At The Art Institute of Chicago. Photo:mark6mauno/Flickr The term relational aesthetics was coined in 1997 by Nicolas Bourriaud, who used it describe a new turn in art exhibits of the 1990s that emphasized “the community effect in contemporary art.” As Bourriaud explains, relational aesthetics describes “an art taking as its theoretical horizon the realm of human interactions and its social context, rather than the assertion of an independent and private symbolic space.” A famous example is Felix González-Torres’s Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) (1991), which consisted of a pile of hard candies in colorful, cellophane wrappers that viewers were invited to share, a pile whose ideal weight was 175 pounds, the same as the artist’s lover before he contracted AIDS. Visitors to the exhibit space, who might have questioned whether or not to take a candy, were thus brought into relation with the Ross and the artist, with the AIDS epidemic, with each other, and with the space of the exhibit, those evolving and ephemeral relations becoming the object of art.

Relational aesthetics has been said to be participatory not contemplative; intersubjective not private; contingent not portable; collective not personal; part of service-based economy not goods-based economy; politically provisional and pragmatic not utopian; collaborative not confrontational; millennial not postmodern; a theory of recognition not otherness; and open-ended not whole or complete.

As used commonly, then, relational aesthetics refers to the work of a particular time and place: institutional art exhibits from the 1990s to the present. And yet, similar notions of relationality are familiar across a broad historical spectrum of thinking about art and literature.

A similar aesthetics of community took shape beginning in the 1890s in the international fad for ephemeral bibelots, many of which were dependent for their aesthetic charge upon the dynamics of circulation and community. Indeed, I argue that it makes sense to think of the 1890s as a relational era in Modern art. Relations were central to Claude Debussy’s assertion that “music is the space between the notes,” William James’s radical empiricism, and Eadweard Muybridge’s sequential photographs of movement. Decadence has been framed by some critics as depending on a relational modality that gave way to autonomy in twentieth-century modernism.

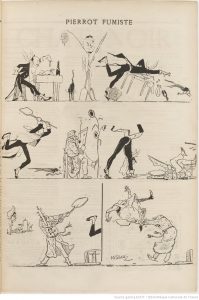

Pierrot Fumiste in Le Chat Noir. Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothéque Nationale de France. Le Chat Noir, 1882/03/25 (A1,N11). In France, relational aesthetics was sometimes known as fumisme, sending something up in smoke, and it anticipates Dada and Surrealism. Relational aesthetics distinguishes the artistic élan of the ephemeral bibelots from the Realism most often associated with William Dean Howells, which was based on direct and unadorned representation of local, everyday life. Relational aesthetics is also different from early twentieth-century modes like Imagism and from the development of indigenous avant-gardes as described recently in books on modernist little magazines by Eric Bulson and Eric White.

Relational aesthetics structures the reception of artwork in the bibelots from this period. A study of the formation of relations in the context of international circulation of ideas about bibelots, which were not, themselves, distributed internationally, helps us better understand the dynamics of print culture. Aesthetic innovation, to give one important for instance, is often attributed to authors who bridge structural holes between otherwise distinct coteries of up-to-date insiders.

-

Not online.

While it is true that many of the ephemeral bibelots can now be accessed at HathiTrust, the GoogleBooks of academic libraries, a large percentage of them are not there. Most of the research for Ephemeral Bibelots was conducted at the Zimmerli Museum at Rutgers, which, as part of its deep collection of fin-de-siècle materials has a full run of Le Chat Noir, and at Princeton University’s Library of Rare Books and Special Collections. I also consulted collections at the Huntington, Berkeley, Yale, Harvard, Wisconsin and the NYPL.

Look on this website for PDFs of the full run of the Lark and M’lle New York. Avoid HathiTrust for these as their copies are incomplete.

A number of runs of Le Petit Journal des Refusées, which varied in color and layout, can be found at the Modernist Journals Project: http://modjourn.org.

-

Some of the period’s most important authors were involved with the bibelots, most notably Henry James, Kate Chopin and Stephen Crane. The bibelots also draw attention to many other exceptionally interesting but forgotten artists, including Stuart Merrill, an American poet who was part of Mallarmé’s circle, unfamiliar to American scholars because he wrote in French and to French scholars because he was American, and Gelett Burgess, editor of several key bibelots who coined the word “blurb” in 1907. A number of popular women writers got their start in the bibelots, for instance Juliet Wilbor Tompkins and Carolyn Wells. The graphic artists Will Bradley, Louis Rhead, and John Sloan contributed illustrations, many of which featured the American dancer Loie Fuller who had made a namer for herself in the cabarets of Paris.

Gelett Burgess was the most iconoclastic bibelot editor of the late 1890s. Even though most people don’t know Burgess today, he was, for a brief stint in the late 1890s, at the absolute forefront of the spread of modern art in America. He was the country’s most significant figure in the craze for ephemeral bibelots, and the buzz about his work would not have been dissimilar from what he had to say of the French Modernists. It was the source of bewilderment. He was the editor and main creative talent behind the Lark, Le Petit Journal des Refusées, Phyllida: or, the Milkmaid, and L’Enfant Terrible–all of these, and especially the first two, being at the very center of the tightly networked coterie of the aesthetic public sphere. That Burgess has been so completely disentangled from the history of American avant-gardism leads me to want to argue that one of the most interesting things about him is his inconsequentiality. He is, at the very least, the most inconsequential major artist of America’s fin de siècle.

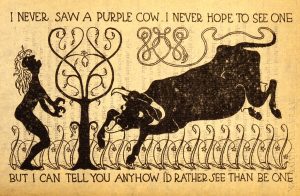

If Burgess is remembered today, it is for a short quatrain, “The Purple Cow,” which he first published in the Lark in 1895.

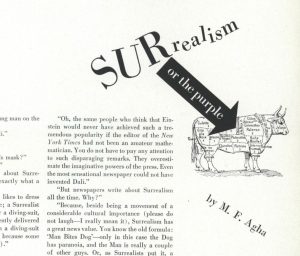

Gelett Burgess, “The Purple Cow,” the Lark no. 20. When Vogue introduced Salvadore Dali to its readers in 1936, they did so by way of a reference to this quatrain, an essay titled “Surrealism or the Purple Cow.”

“Surrealism, or the Purple Cow.” Vogue 88.9 (Nov 1, 1936) -

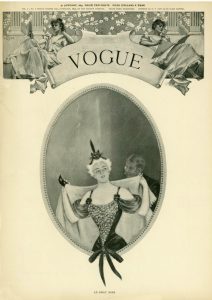

I’ve always loved the short stories of Kate Chopin. She published extensively in Vogue in the 1890s, and I had decided to take a look at what her stories looked like in that context. I was astonished by what I found there. Vogue was exceptionally progressive and beautifully decorated by Art Nouveau illustrations, which made sense given Chopin’s stories. It was perfect. But then, there were also the bizarre covers, especially the one I discuss in the Prologue of a young debutante at the opera wearing a black cat on her head. This book started as a simple attempt to figure out what that image meant. The answer opened up an entire class of writing unknown to American literary history.

Cover of Vogue, January 31, 1895, “LE CHAT NOIR” -

There is so much, starting with fact that Vogue was making an impressive feminist statement by publishing Kate Chopin alongside a sexually provocative parody of a fin-de-siècle French cabaret.

• There was an international fad for little art journals, the “ephemeral bibelots,” decades before the more well-known modernist little magazines of the 1910s and 1920s began to appear.

• Gellet Burgess and his astonishing bohemian artwork in the ephemeral bibelots was an amazing discovery. Burgess made his name in San Francisco. It has been a delight running into people who have heard of his nonsense quatrain, “The Purple Cow” (“I never saw a purple cow, I never hope to see one, but I can tell you, anyhow, I’d rather see than be one!”). Knowing about Burgess means reconsidering late nineteenth-century American literature, which is almost always considered in terms of a Realism that Burgess despised.

• Well-known American authors like Henry James and Stephen Crane were involved in the ephemeral bibelot movement, knowing which changes how we read them. Crane’s poetry, especially, becomes revitalized when returned to the context of the bibelots, where it is seen to exemplify the Modern and the new in a period still trying to figure out what such things meant.

• There is a massive amount of writing by American women writers, like Juliet Wilbor Tompkins and Caroline Wells, that simply has not been attended to by scholars. What I have provides is only an opening salvo in the recovery of commercially successful American women writers whose fiction centered on strong heroines and pushed for a franker discussion of sex and marriage.

• One reason the vogue for the bibelots ended was that the Modernists of the later period actively rejected it.

-

• That bohemianism and Modern art only arrived in the United States sometime around the famous Armory Show of 1913.

• That Stephen Crane was way ahead of his time as a poet, in the words of Amy Lowell a “man without a period… [who] sprang from practically nowhere.”

• That art considered “innovative” is “original.” In fact, innovation seems to be a product of network dynamics, not originality. It is innovative for circulating material between otherwise disparate and disconnected groups of artistic insiders.

-

I hope that it makes this visually stunning archive unavoidable in accounts of American literary and artistic history. Discussions of major authors, and also of topics ranging from sex to print culture, will have to include an account of the little era of revolt initiated by the bohemians of the bibelot vogue. If the book works, readers should take away a new sense of excitement about the extraordinary experiment in print culture represented by the international fad for ephemeral bibelots.