While it is commonly known that fingerprint identification has played an important role in the history of policing and forensic science, there is another aspect of the history of fingerprinting that is less well understood: how fingerprints have been studied in the sciences. The scientific study of fingerprint and palm patterning is referred to as “dermatoglyphics,” a term that was invented in the 1920s.

Image: Harris Hawthorne Wilder and Bert Wentworth. Personal Identification: Methods for the Identification of Individuals, Living Or Dead. Boston: Richard G. Badger, The Gorham Press, 1918, 139. Public domain.

When this field was first developing at the turn of the 20th century, those who conducted scientific research on fingerprints were preoccupied with the question of whether minute anatomical differences in the fingerprints could be used to distinguish between different “races.” Those who carried out these early anthropological studies of fingerprints were proponents of ideas about race, eugenics, and biological determinism that were disparaging and abhorrent [1]. While many of these ideas would be abandoned over time, dermatoglyphics researchers would continue to investigate the different frequencies with which fingerprint characteristics appear in different populations (a subject discussed in more detail here).

Throughout the 20th century, a large amount of research would be done on the anthropological, genetic, and medical aspects of fingerprint patterning. Those who worked in the field of dermatoglyphics would develop close ties with other established scientific fields (serology, population genetics, medical genetics, and so on). At the same time, dermatoglyphics would develop into a unique scientific discipline in its own right, complete with its own standardized methodologies, formal knowledge, and scholarly associations.

One of the most important books in this field was called Finger Prints, Palms and Soles: An Introduction to Dermatoglyphics, which was published in the early 1940s. This work was a synthesis of all existing dermatoglyphics knowledge (up until that point) and provided a foundation for research in this field during the second half of the 20th century. It is a book that continues to be cited today in the academic and professional literature on fingerprint identification.

Image: Harold Cummins and Charles Midlo. Finger Prints, Palms and Soles: An Introduction to Dermatoglyphics. New York: Dover Publications, 1961, title page. Used with permission. Image courtesy of Dover Publications.

For more on the history of dermatoglyphics, watch this short lecture.

Before examining some of the specific areas of research that were carried out in dermatoglyphics, it is worth briefly considering how the scientific study of fingerprints differed from the techniques of personal identification that were used in policing and forensic science. For one thing, dermatoglyphics research was based on the assumption that fingerprints could reveal more about a person than simply who they were – the central question in personal identification [2]. Identification was never the primary concern of dermatoglyphics research.

We find a visual representation of the idea that fingerprints could be used for more than personal identification in this cartoon from the early 1930s. It suggests that a person’s fingerprints might reveal “the vocation for which nature intended them,” in this case leading to the conclusion that “he’ll make a good plumber!”

Image: “Character Tips In Finger Tips! Read ‘Em And Weep!” The China Press (June 20th, 1933), p. 9, 14. NEA © NEA Inc. Reprinted by permission of ANDREWS MCMEEL SYNDICA.

While researchers in dermatoglyphics were not actually concerned with using fingerprints to determine one’s ideal occupation, they were interested in examining skin ridge patterning of the fingers and palms in order to reveal various other things about a person. Over the 20th century, for example, much research would be devoted to correlating fingerprint and palm patterns with particular congenital or health conditions such as Down syndrome (discussed further below). The ambitions that underlay such research went far beyond personal identification.

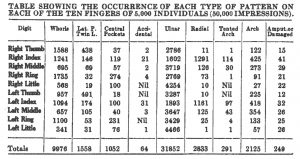

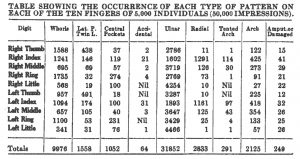

Another way that dermatoglyphics research was different from personal identification was that researchers in this field often analyzed fingerprints at the level of groups and populations. Ever since the invention of modern fingerprint identification, police officials and academic researchers had been aware that certain patterns were more common than others within the population. The following chart, for example, describes the fingerprint pattern-types that were observed on the fingers of 5,000 people (the data was collected by Scotland Yard).

Note: This image might not display properly on smaller screens.

Image: Harris Hawthorne Wilder and Bert Wentworth. Personal Identification: Methods for the Identification of Individuals, Living Or Dead. Boston: Richard G. Badger, The Gorham Press, 1918, 212. Public domain.

One of the reasons that dermatoglyphics researchers were so interested in this kind of data was because it provided a picture of the most common types of fingerprint patterning that appeared within a given population. For example, according to this chart, whorls constituted about 20% of the fingerprint pattern-types that were observed in this population, whereas arches (including tented arches) only constituted about 5%. Understanding how frequently particular pattern-types appeared in the population was something that seemed to demand additional research.

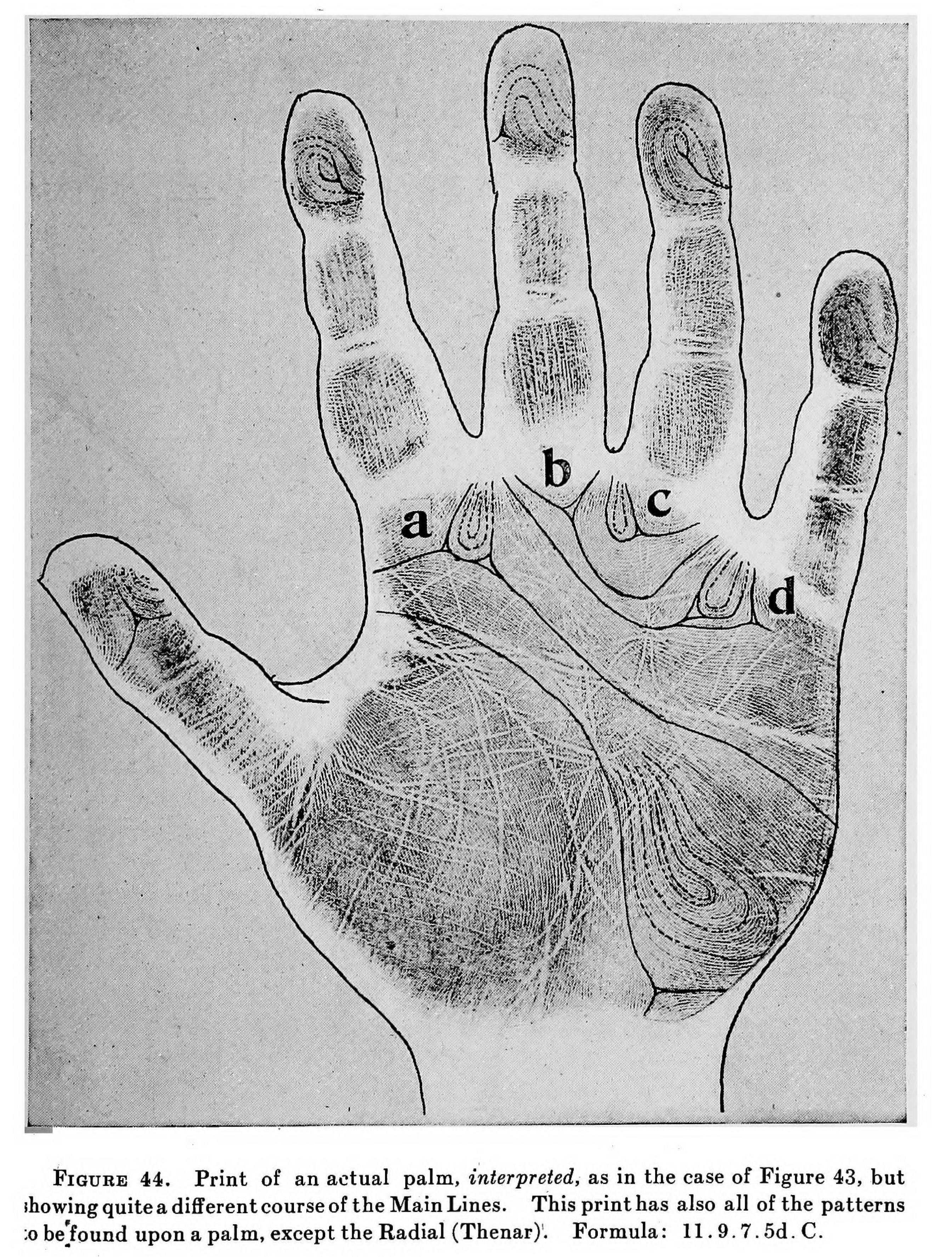

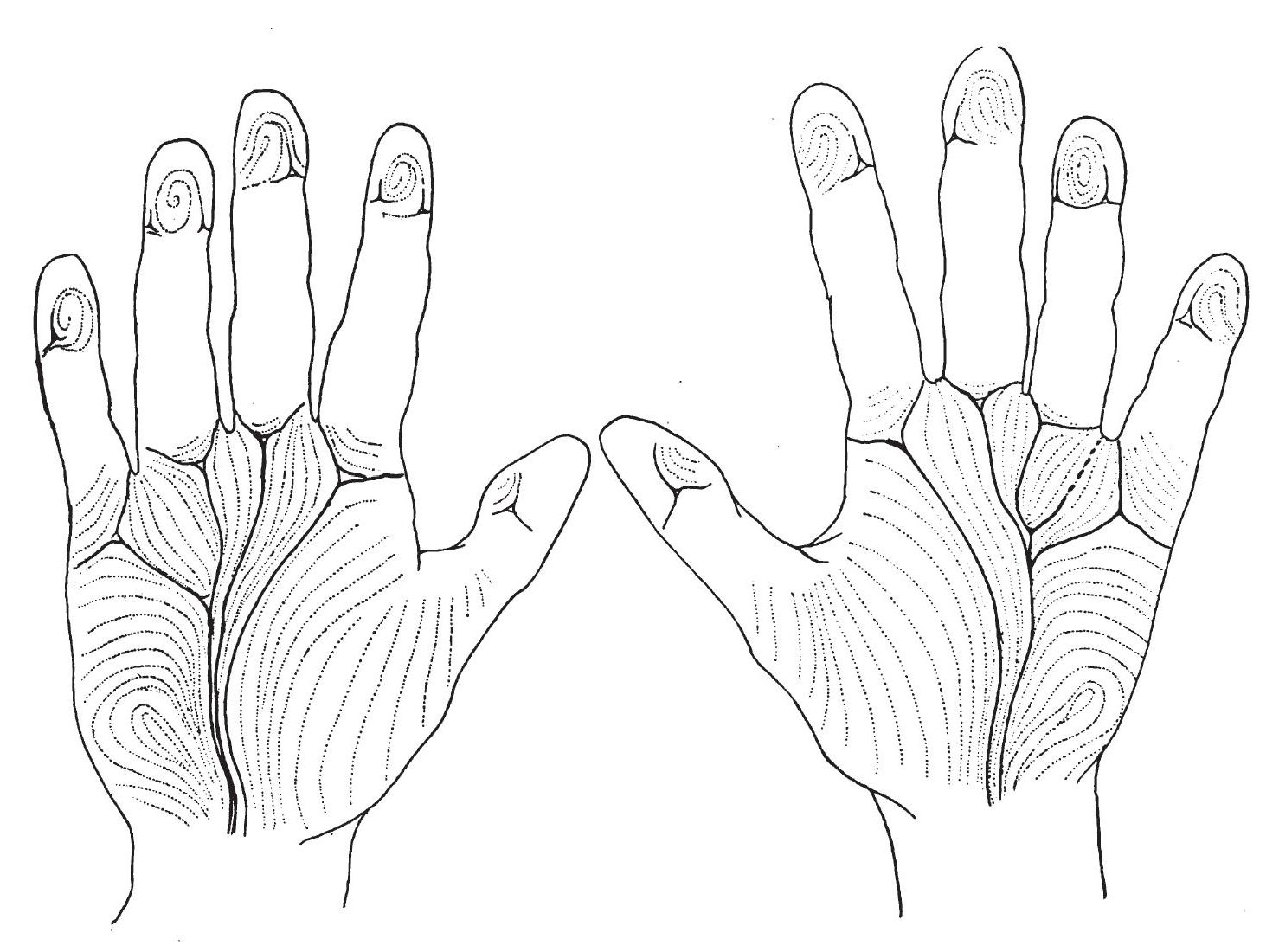

As researchers did more and more of this kind of work (and also refined their methods for describing fingerprint and palm patterning), they developed an understanding of what counted as the most common or, in their view, “normal” kinds of patterns. This meant, for example, that when the following examples of palm patterning were encountered by researchers early in the 20th century, they were immediately recognized as being unusual. With main lines on the left palm that traveled in an extreme vertical direction, this individual’s palm patterns were “totally unlike any in a collection of the palm prints of some 1100 individuals,” in the words of authors Wilder and Wentworth.

Image: Harris Hawthorne Wilder and Bert Wentworth. Personal Identification: Methods for the Identification of Individuals, Living Or Dead. Boston: Richard G. Badger, The Gorham Press, 1918, 368. Public domain.

On the basis of this kind of work, dermatoglyphics researchers also came to investigate how “abnormal” fingerprint and palm patterning might reveal the presence of congenital or other health conditions.

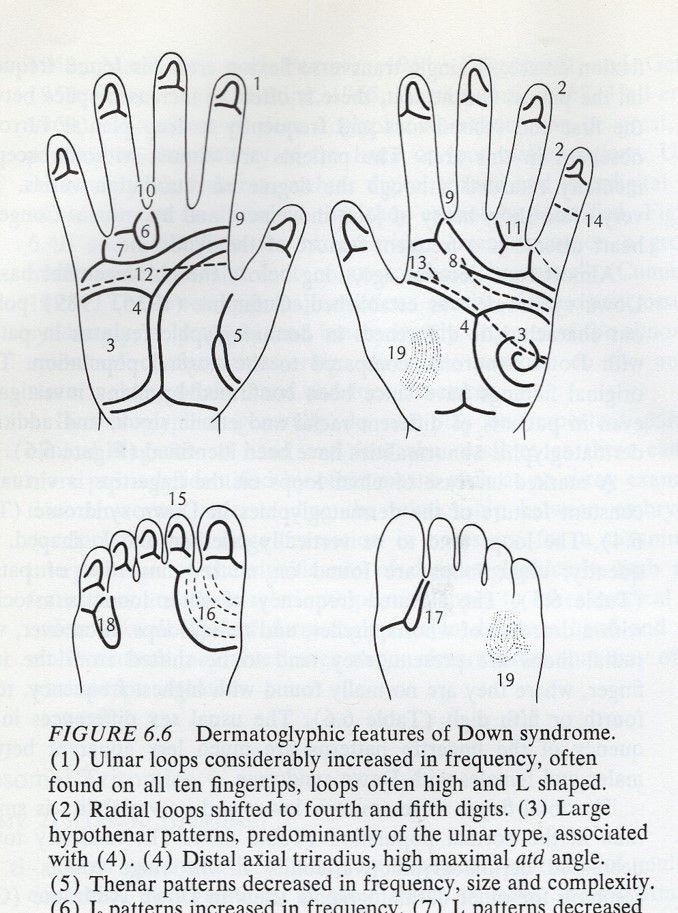

During the 1950s and 1960s, for example, researchers examined the relationship between various medical conditions and observed abnormalities in fingerprint and palm patterning [3]. This image shows some of the physical manifestations of Down syndrome, a chromosomal disorder that was a major focus of dermatoglyphics research during this period.

Image: Reprinted/adapted by permission from Springer Nature: Springer-Verlag, Dermatoglyphics in Medical Disorders by Blanka Schaumann and Milton Alter, Copyright Springer (1976). Figure 6.6, p. 148.

Another focus of dermatoglyphics was the genetic inheritance of fingerprint patterning. Researchers attempted to understand how one’s fingerprints might be influenced by the genes inherited from one’s biological parents. Doing such work required thinking about fingerprint patterns in terms of the similarities and differences that could be observed across multiple (genetically-related) individuals. This was another area of dermatoglyphics research that was far removed from the fingerprint identification practices that most interested police officials and forensic professionals.

Researchers such as the geneticist Sarah B. Holt studied similarities and differences in the fingerprint characteristics of genetically-related individuals (Holt focused on the Total Finger Ridge Count, or the number of ridges found on all of one’s fingerprints, in her studies). The key finding that emerged from this work was that genes play a role in influencing certain aspects of fingerprint patterning.

Image: Sarah B. Holt. The Genetics of Dermal Ridges. Springfield: Charles C Thomas · Publisher, 1968. Courtesy of Charles C Thomas Publisher, Ltd., Springfield, Illinois.

Today researchers look to DNA as the most important source of information about human genetics. Prior to the rise of human genetics based on molecular biology, however, there were few reliable genetic markers that could be used in research on human heredity. In fact, alongside blood type (which is genetically inherited in predictable ways and not affected by one’s environment), fingerprints were also viewed as a potentially useful genetic marker that could be used in scientific research.

Writing in the early 1950s, the geneticist David C. Rife (1901-1992) explained the potential value of fingerprints for genetics research in the following way:

Dermatoglyphics [that is, palm and fingerprint patterns] provide a tool of unique value for human geneticists and physical anthropologists. The configurations are established long before birth and are not altered by age (except in size), and post-natal environmental circumstances. Permanent and accurate records may be obtained from an individual in a few minutes. Individual records require only a few sheets of paper, and hundreds of such records may be carried in a small traveling bag. Unlike blood samples, dermatoglyphics are not subject to spoilage and may be analyzed years after they are taken [4].

While seemingly outdated from today’s genetic science – which relies on the study of DNA – this passage gives a sense of the scientific meaning that fingerprints had earlier in the 20th century. Some researchers even attempted to develop fingerprint-based paternity tests that could be used in court to establish the genetic relationship between a child, known biological parent, and suspected parent [5]. In such tests, fingerprint patterning was viewed as a genetic marker.

For more on the use of fingerprints in the study of human genetics, watch this short lecture.

From today’s perspective, it might seem strange or far-fetched that fingerprints could ever serve as a genetic marker or a physical feature with medical significance or scientific meaning.

In this context, it is striking – perhaps even surprising – just how much time and effort was spent on this area of scientific research earlier in the 20th century. In the post-WWII period there were even academic associations such as the International Dermatoglyphics Association and American Dermatoglyphics Association that supported scholarly exchange in this field and even sponsored their own publications [6].

Image: Newsletter of the American Dermatoglyphics Association 4, nos. 1 & 2 (1985). National Anthropological Archives (NAA), Smithsonian Institution, American Dermatoglyphics Association Records, Box 3. Image courtesy of NAA.

Take a closer look at the logo of the American Dermatoglyphics Association below. This striking image speaks to the broad ambitions of those who pursued research in this field. The key areas of friction ridge skin – hands, fingers, feet, and toes (both human and non-human) – are represented in the inset, while the outer ring of words gives an indication of the various fields (anthropology, medicine, primatology, law, identification, embryology, and genetics) that intersected with the concerns of dermatoglyphics.

Note: This image might not display properly on smaller screens.

In the end, dermatoglyphics did not yield the most ambitious and hoped-for results in these various areas. For example, it became clear over time that examining fingerprint and palm characteristics only had limited value for clinical diagnosis in medicine. More generally, molecular biology has come to provide much more powerful ways of studying and addressing the anthropological, medical, and genetic questions that most interested dermatoglyphics researchers.

Sources

[1] Simon A. Cole. Suspect Identities: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002, 98-99, 105-109, 110, 113-114.

[2] For more on this point, see Cole, Suspect Identities, 97-118 as well as Simon A. Cole. “De-neutralizing identification: S. & Marper v. United Kingdom, biometric databases, uniqueness, privacy and human rights.” In Identification and Registration Practices in Transnational Perspective: People, Papers and Practices, edited by Ilsen About, James Brown, and Gayle Lonergan, 77-97. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

[3] Fiona Miller. “The Importance of Being Marginal: Norma Ford Walker and a Canadian School of Medical Genetics.” American Journal of Medical Genetics 115, no. 2 (2002): 102-10; Fiona Alice Miller. “Dermatoglyphics and the Persistence of ‘Mongolism’: Networks of Technology, Disease and Discipline.” Social Studies of Science 33, no. 1 (2003): 75-94; Daniel Asen, “Secrets in fingerprints: clinical ambitions and uncertainty in dermatoglyphics.” CMAJ May 14, 2018, 190 (19) E597-E599.

[4] David C. Rife. “Finger Prints as Criteria of Ethnic Relationship.” American Journal of Human Genetics 5, no. 4 (1953): 389-399, quote from p. 389.

[5] Daniel Asen. “Fingerprints and Paternity Testing: A Study of Genetics and Probability in Pre-DNA Forensic Science.” Law, Probability and Risk 18, nos. 2-3 (2019): 177-199.

[6] Daniel Asen. “‘Dermatoglyphics’ and Race after the Second World War: The View from East Asia.” In Global Transformations in the Life Sciences, 1945–1980, edited by Patrick Manning and Mat Savelli, 61-77. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2018, 70-71.