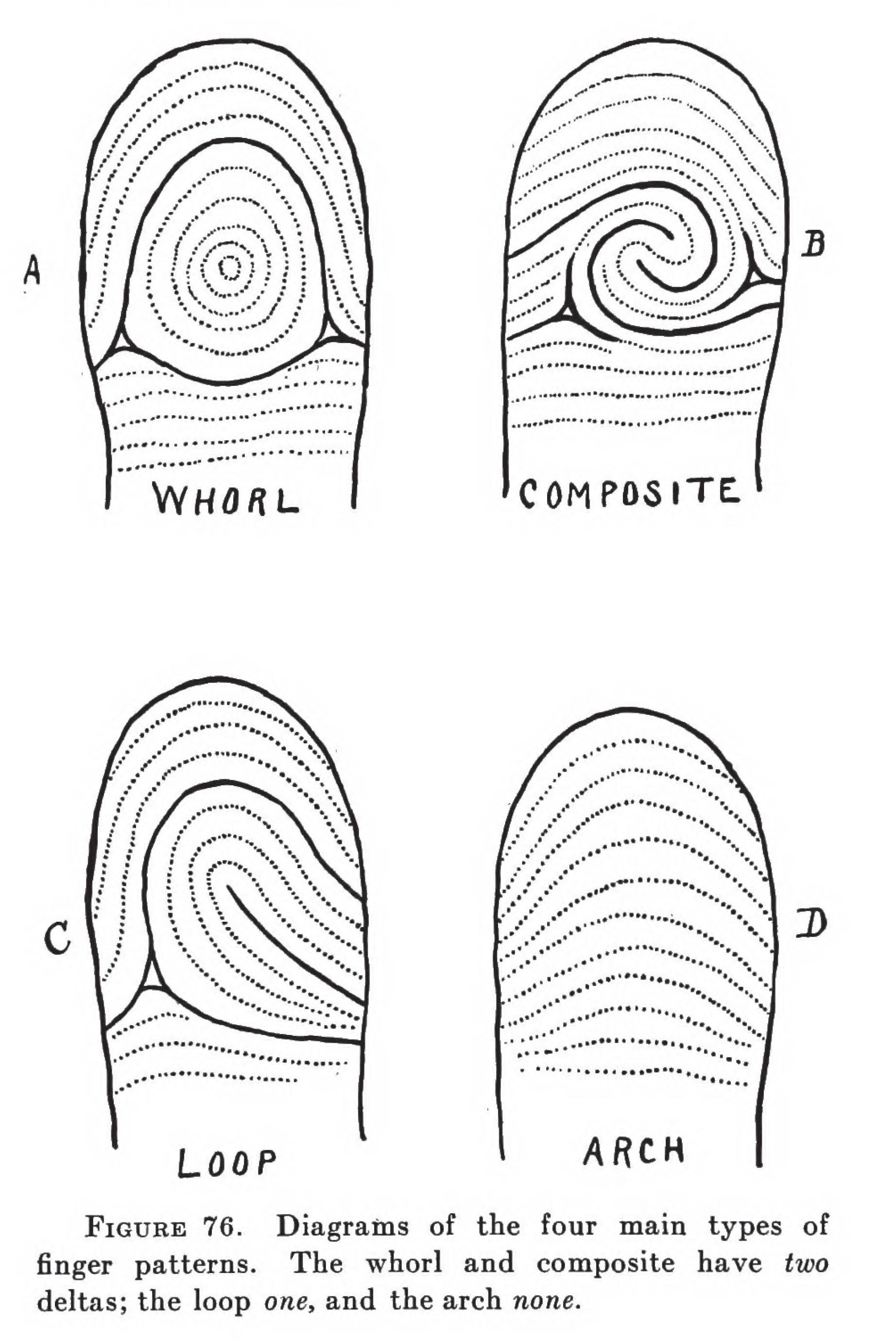

Image: Harris Hawthorne Wilder and Bert Wentworth. Personal Identification: Methods for the Identification of Individuals, Living Or Dead. Boston: Richard G. Badger, The Gorham Press, 1918, 188. Public domain.

Image: Harris Hawthorne Wilder and Bert Wentworth. Personal Identification: Methods for the Identification of Individuals, Living Or Dead. Boston: Richard G. Badger, The Gorham Press, 1918, 188. Public domain.

Image: Harris Hawthorne Wilder and Bert Wentworth. Personal Identification: Methods for the Identification of Individuals, Living Or Dead. Boston: Richard G. Badger, The Gorham Press, 1918, 125. Public domain.

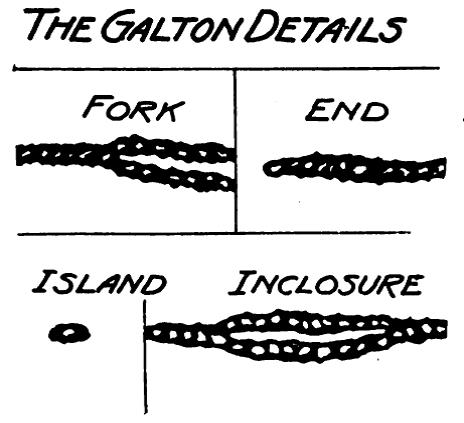

Image: Francis Galton. Finger Prints. London: Macmillan and Co., 1892, Plate 15, Figure 22, following p. 96. Public domain.