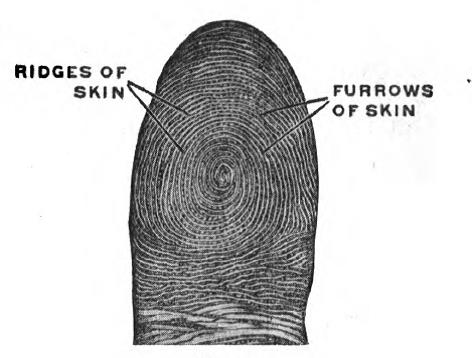

Humans have known about fingerprints for a long, long time. People in different societies throughout history have left their fingerprints on a wide range of artifacts and documents. Sometimes impressions of the fingers were left unintentionally – for example, by the artisans who made figurines and oil lamps in ancient Roman ceramics workshops [1] – but sometimes fingerprints were recorded deliberately and for specific purposes.

Image: University of Applied Science. A Study in Finger Prints: Their Uses and Classification. Third Edition. Chicago: University of Applied Science, 1920, 37. Public domain.

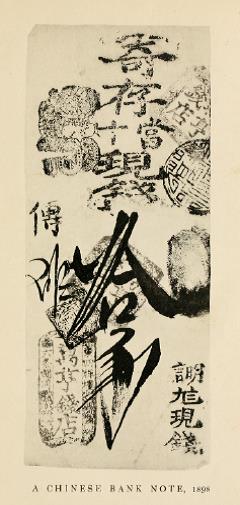

In pre-modern China, for example, inked finger and palm impressions were used as a kind of signature on contracts and other documents. An inked fingerprint could also be placed on documents as a way of verifying their authenticity should a dispute arise later on. This practice was mentioned by an acquaintance of William J. Herschel (1833-1917) – a British colonial official who played an important role in the development of modern fingerprinting – when describing his experiences in China during the mid-19th century.

According to this observer, inked finger impressions were given on Chinese banknotes:

… Chinese bankers had been in the habit of impressing their thumbs on the notes they issued …

“[Finger impressions] are imprinted partly on the counterfoil and partly on the note itself, so that when presented its genuineness can be tested at once.” [2]

Thus, by putting the two parts side by side – and matching up the fingerprint that lay across them – one could verify the document’s authenticity.

Image: William James Herschel. The Origin of Finger-Printing. London: Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press, 1916, after p. 38. Public domain.

When we talk about “fingerprinting” today, we are usually referring to something fairly specific – namely, examining and comparing fingerprints as a means of personal identification. This way of using fingerprints is relatively recent, in fact, and grew out of developments that happened in the mid-late 19th century. An important site for these developments was British India [3].

For more on the colonial origins of modern fingerprinting, watch this short lecture.

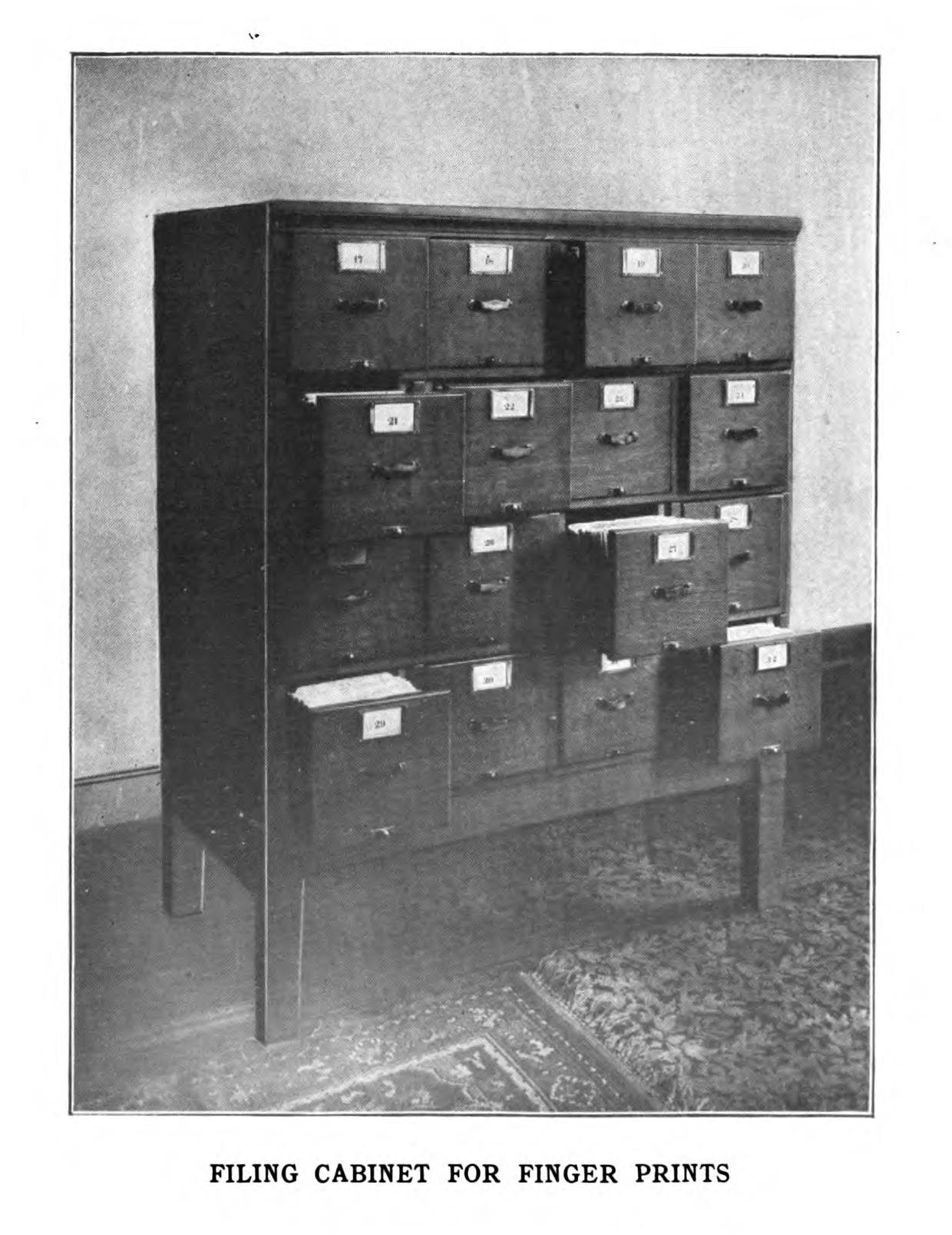

It was only in the last decade or so of the 19th century that officials started to develop identification registries that could be used to identify an individual on the basis of their fingerprints. These files contained fingerprint cards that were stored in filing cabinets and arranged in a specific manner that facilitated their later retrieval.

This was a crucial turning point in the development of modern fingerprint identification (and for police identification practices more broadly). It was now possible for police or other government officials to accurately identify an unknown person on the basis of marks that appeared on the body itself rather than having to rely on the name that they gave or identity documents that they provided.

Image: Frederic Augustus Brayley. Brayley’s Arrangement of Finger Prints Identification and Their Uses. Boston: The Worcester Press, 1910, 10. Public domain.

For more on the invention of paper-based fingerprint registries, watch this short lecture.

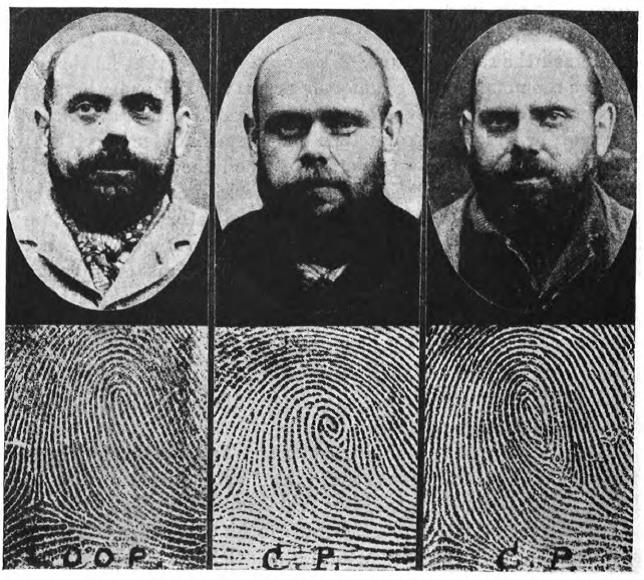

The powerful new identification capabilities afforded by fingerprinting were visually depicted in images such as the following, which made the point that identifying a person on the basis of fingerprints was far more reliable than simply looking at their physical appearance. Even people with extremely similar physical appearances – as in this image – have fingerprints that can be easily differentiated.

Image: Harris Hawthorne Wilder and Bert Wentworth. Personal Identification: Methods for the Identification of Individuals, Living Or Dead. Boston: Richard G. Badger, The Gorham Press, 1918, 30. Public domain.

At this early stage, however, it was not obvious that fingerprinting was the most effective method of personal identification. There was another method – based on measurements of various parts of the body – that was widely used at the time. This alternate method is usually referred to as “Bertillonage” in reference to its creator, a French police official named Alphonse Bertillon (1853-1914). People who lived around the turn of the 20th century still considered Bertillonage to be a powerful identification technique. It was not at all obvious that identification by body measurements would eventually be replaced by fingerprinting. Over time, the use of Bertillonage would decline while fingerprint identification came to be widely adopted [4].

To learn about the history of Bertillonage and its replacement by fingerprinting, watch this short lecture.

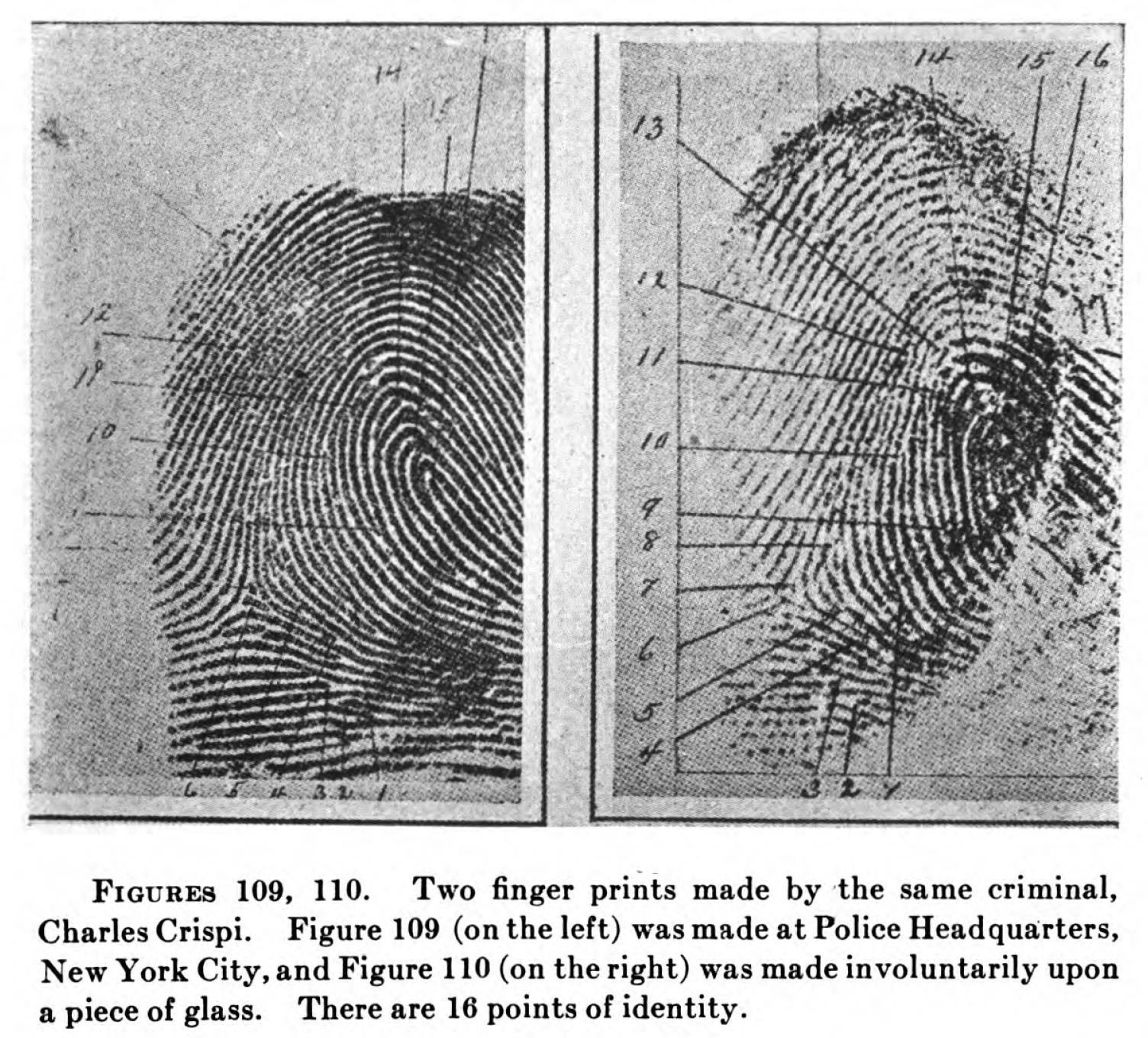

Over subsequent decades, fingerprinting would be used not only for the identification of suspects and convicts in police registries, but also in the new field of crime scene evidence, where latent fingerprints – marks left at a crime scene in blood, sweat, or other substances – would become an important source of evidence for police and legal authorities around the world.

Image: Harris Hawthorne Wilder and Bert Wentworth. Personal Identification: Methods for the Identification of Individuals, Living Or Dead. Boston: Richard G. Badger, The Gorham Press, 1918, 287. Public domain.

For classroom handouts showing how crime scene fingerprints are collected and analyzed, click here and here (courtesy of Kimberlee Sue Moran).

For some of the innovations that have transformed fingerprint identification over the 20th century, watch this short lecture.

Sources

[1] Achim Lichtenberger and Kimberlee S. Moran. “Ancient fingerprints from Beit Nattif: studying Late Roman clay impressions on oil lamps and figurines.” Antiquity 92, no. 361, e3 (2018): 1-6.

[2] William James Herschel. The Origin of Finger-Printing. London: Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press, 1916, 38.

[3] The colonial origins of fingerprint identification can be followed in Simon A. Cole. Suspect Identities: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002 as well as in Chandak Sengoopta. Imprint of the Raj: How fingerprinting was born in colonial India. London: Macmillan, 2003.

[4] Cole, Suspect Identities, 32-59.