Research

Compassion is a deliberate habit of mind, a trainable skill that becomes automatic and less effortful with practice. One promising strategy is compassion training that involves making positive well-wishes for others within and beyond individuals’ immediate social ties. Growing evidence suggests that compassion training can promote physical health, strengthen social bonds, and restore humanized perceptions toward diverse groups.

The central goal of our research is to understand the nature and consequences of compassion. To this end, we aim to 1) understand mechanisms of compassion, which then informs 2) theory-driven development and implementation of interventions designed to spread compassion through social networks. We take multimethod approaches that integrate experimental and behavioral paradigms, computational neuroimaging techniques (fMRI, fNIRS), ecological momentary assessment (EMA), social-network analysis, and natural language processing. We have applied these methods to several areas of social and health behaviors described below.

Neural bases of compassion effects on health

People can choose to become healthier, but they often don’t. This speaks to some of the fundamental limitations of human cognition that nudge people into dismissing beneficial health recommendations. One such cognitive barrier is self-enhancement motives, which may motivate individuals to become defensive when confronted with self-relevant health information.

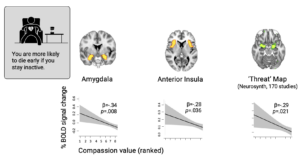

We tested whether compassion would shift people’s attention away from the threatened aspect of the self to the well-being of others, thereby decreasing defensiveness to beneficial health information. We found that individuals who pursue compassionate goals over self-enhancing goals were less likely to show activity within neural regions associated with threat processing when exposed to potentially threatening health messages (Kang et al., 2017, Psychosomatic Medicine). These results suggest that one way through which compassion benefits health may be by reducing neural indicators of threat in response to information that could potentially undermine one’s self-worth.

We tested whether compassion would shift people’s attention away from the threatened aspect of the self to the well-being of others, thereby decreasing defensiveness to beneficial health information. We found that individuals who pursue compassionate goals over self-enhancing goals were less likely to show activity within neural regions associated with threat processing when exposed to potentially threatening health messages (Kang et al., 2017, Psychosomatic Medicine). These results suggest that one way through which compassion benefits health may be by reducing neural indicators of threat in response to information that could potentially undermine one’s self-worth.

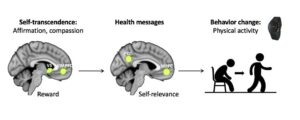

To directly manipulate compassion effects, we conducted a three-armed randomized controlled fMRI study that compared two types of compassion-based interventions (Kang et al., 2018, PNAS). At-risk individuals were randomly assigned to complete compassion training, compassion affirmation (reflecting on compassionate values), or control task, followed by evaluating messages promoting physical activity.

Both types of compassion interventions, in the moment, elicited greater activity within the brain’s reward and mentalizing networks. During the subsequent health messages intervention, the two compassion-based intervention conditions, relative to control, produced comparable increases in activity within the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC), implicated in self-relevance and positive valuation. Importantly, increased VMPFC activity mediated the effect of compassion interventions on increases in physical activity as measured by accelerometers in the following month. These findings suggest that compassion may engage reward and social processes, which in turn allows people to consider self-relevance of messages that might otherwise pose a threat to self-worth.

Both types of compassion interventions, in the moment, elicited greater activity within the brain’s reward and mentalizing networks. During the subsequent health messages intervention, the two compassion-based intervention conditions, relative to control, produced comparable increases in activity within the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC), implicated in self-relevance and positive valuation. Importantly, increased VMPFC activity mediated the effect of compassion interventions on increases in physical activity as measured by accelerometers in the following month. These findings suggest that compassion may engage reward and social processes, which in turn allows people to consider self-relevance of messages that might otherwise pose a threat to self-worth.

Neural bases of compassion effects on social perceptions

Negative attitudes against stigmatized outgroups arise in part from failures to perceive group members as fully human, and hence not as social targets. Therefore, strategies that restore other-oriented social processing may promote positive attitudes toward outgroup members. In a series of randomized controlled experiments, we showed that compassion training can decrease implicit bias against individuals who are often dehumanized due to different cultural and historical causes, including racial, socioeconomic, and health status. In an initial study, we found that participants who completed the 6-week compassion training, compared to those who discussed compassion (matched active control) or were wait-listed, showed greater decreases in implicit bias (Kang et al., 2013, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General; Kang et al., 2015, Mindfulness).

To further characterize how compassion training may alter neural signals in response to marginalized outgroups, we randomly assigned participants to complete either a 4-week compassion or control intervention and monitored changes in implicit bias against individuals addicted to drugs (Kang et al., 2020, Mindfulness). Participants who completed a compassion intervention, compared to controls, showed greater decreases in implicit bias over time. In the brain, a compassion task, compared to control, evoked greater activity within a neural region central to considering mental states of others (right TPJ), which mediated the effect of compassion training on bias reduction. By boosting mentalizing signals in the brain, considering the well-being of others through compassion training may help regard otherwise dehumanized individuals with a sense of humanity, having needs and suffering shortcomings that are intrinsic to being a human.

Compassion in interpersonal relationship

Feeling understood is foundational to healthy interpersonal relationship. To characterize neural and behavioral effects of compassion in dyadic interactions, we conducted a study using functional near infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). Participants were randomized to complete compassion training or a control activity prior to listening to someone’s emotional life story while their neural activity was monitored. Participants also inferred the speaker’s emotion throughout the story and provided verbal support to the speaker. We found that compassion training enhanced empathic accuracy and the quality of subsequent verbal support. Interestingly, for those in the control condition, the degree to which their neural activity within the mentalizing network synchronized with that of a speaker predicted empathic accuracy. These results suggest that compassion training enhances the ability to accurately track genuine emotional displays that dynamically fluctuate across naturalistic narratives. Further, compassion and neural synchrony may complement each other to promote interpersonal understanding. While compassion practice might be particularly beneficial when communicators are less “in sync” with each other, neural synchrony might be more important for accurate understanding when people are less motivated to be compassionate.

Upcoming work: Compassion traveling through social networks and building compassion

Our health behavior is largely shaped by social interactions in the real world (Pandey, Kang, et al., 2021, Health Psychology). However, most existing preventive efforts focus on individual-level drivers of change, and creating long-term adherence beyond the initial intervention period has been challenging. Our upcoming work will focus on identifying social network-level contributors to health and test the real-world scope of intervention effects by integrating social network analysis.

The first goal is to understand how effects of prevention strategies spread through social networks. Pilot data show that highly compassionate individuals are more central (vs. peripheral) within their social network, suggesting that multilevel prevention efforts may rely on these individuals as intervention champions.

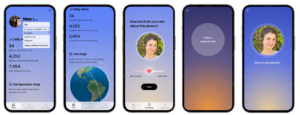

Our next goal is to optimize intervention delivery and prepare for population-level implementation. We are in the process of developing a mobile compassion application that delivers personalized daily compassion training sessions.