Komura Jutaro

My Autobiography

(Transcribed by Camille Romano, Emily Sun, and Aishwarya Sridhar)

I was born in a solidarity rural town, three years after the memorable visit of Commodore Perry. I had hardly breathed when the whole country felt a great shock which proved more direct in its effects than any ever experienced in Japan. While yet a child, the feudal system existed both in its spirit and form, though in a fast declining state. I was early impressed, therefore, with those ideas of [the] feudality. Although I passed my childhood amid the scenes and circumstances incident to the feudal life and received my early education among the superstitious mass of the country population, I am now living under an improved condition and cultivating myself in the light of science and philosophy. Thus, reflecting upon my past life, I can not hesitate to divide it into two periods; the first ____ rural life and the second that of city life. In the former, I ___ man in his local manners and in the latter, I have ____ing man in his general nature. Locality and generality are what characterize the respective periods of my life as far as it goes.

I was home-bred until four years old. At the age of five, I begun to attend a private school and continued to go there until I was put into a public school. Unfortunately for me, in early childhood, I had a very delicate health and wanted to take medicine “every alternate day” as my grandmother used to say. This circumstance prevented me from making hard study and I made so little progress in the private school, that in point of memory was far below those under my age. My early education was therefore neglected and imperfect. At the age of twelve, I entered the public school, where I studied the Chinese Classics and learnt a bit of the history of Japan. Every-day lessons were, as a whole, easy and simple, although I found sometimes difficulties in composing poems. It was custom of the school to have it opened on the eleventh of the first month. On that particular day, all the school-boys and school-masters congregated together, the head-master read some speeches (usually select pieces taken from the classics) and we were required to bow down before the image of Confucius, Koshi, as we call him. On those days I felt very strange, I remember, to find boys of seven or eight years of age dressed up like men above fifteen. These boys lost their fathers and were obliged to pretend they were in majority, that is, above fifteen, for it was the feudal law that no minor could succeed his father and on the failure of male heirs, a part or the whole of hereditary income should escheat to his lord.

From early childhood, I enjoyed the benefit of associating with men of different orders. I was enabled to form impressions on [trade], agriculture and knighthood. This was the effect of my [peculiar] situation. I took up residence in the town. Looking up northwest from my residence, I could see a castle standing on a rock ____ by nature. Immediately outside the castle, these were the mansions of the chief vassals. There comes the town population and finally, the villages scattered all over the country. During the day, I spent my time in the school filled by the boys belonging to the military ranks. There I had companion of the military society and was animated with romantic spirit and chivalric honor, the subject of every conversation being stories of the old heroes. When I was at home, my associates were town-boys having the profession of trade in view. They would not study anything like the Classics or history, but devoted themselves particularly to the study of arithmetic. I used to go to and fro with an abacus in hand and learnt a bit of arithmetic. It was considered, however, a disgraceful thing for an aristocrat to study the art of arithmetic, and in the school its study was not allowed. Nay, It was even disgraceful to know how to count money. One who should think two and two do not make four was considered more noble than one who knew two times two make four. Trade was regarded as a mean business, and very naturally so, because traders were ignorant and knew no other means of gaining money than by defrauding buyers. If they got money, they knew not how to save it, but by keeping it in a strong box. The term merchant was synonymous to the term either lier or miser. At present, on the contrary, merchants are getting into importance in the social position, and the military class is considered to consist of idle creatures, who earn their living not by their own labor, but by that of farmers, laborers, and traders; that is, they live by their hereditary incomes. Now, to turn to my agricultural employment, I had an uncle who possessed a large farm in the vicinity of the town. When it was the farming season of the year, I used to go to his farm and assist him with hard labor. While I was working hard on the farm, I was [sometimes] discovered by some of my class-mates who happened pass the by-[road] and they often laughed at my low employment as they considered it, but I was quite indifferent. It was here that I had companion of villagers. Although the peasants were subject to heavy burden and consequently obliged to work very hard, yet nothing like poverty existed among them. Each family had, if not in the times of bad [crop], an annual supply sufficient to support all its members and none lived by beggary. They were not, however, allowed to sell or lease their lands until very lately when the government declared that their lands should be their own. They are now absolute proprietors of the soil which they cultivate. This policy was right and expedient, because I consider this to be the rule, that if the farms are large, alienation should be free in order that they may be subdivided and in order that they may be united. The latter part of this rule is the case with Japan. Here, the farms are too much subdivided, and large farms are beginning to appear on consequence of free alienations and demand for lands by rich nobles and merchants. These large farmers will, I hope, introduce machine and try experiments for agricultural improvement. On the whole, the peasants are at present in a more comfortable and happy situation than they used to be. Nevertheless, they rose up in insurrection in some parts. Some may ask, if they had been [are] in a better condition, what made them rise up? This cause may be ascribed to the legislation in advance of the character of people, to the misapprehension on their part of certain Imperial proclamations and finally, to the strict taxation, the last of which has not been noticed by many persons. The discriminate taxation was, in my view, the principal cause of the peasant risings. In the feudal times, there were some villages which enjoyed immunity from taxation by special custom or on account of a particular privilege granted by the lord. At present, all [?] are equally taxed. Feudal privileges and local customs are not regarded and justly so. Local laws giving way for general or national laws, local inconveniences naturally arise, but we can not help this.

Now that I was brought up three years in school, I began to feel patriotic sometimes, though patriotism arising from a mere local prejudice. About this time, the country was in agitation with the question of foreign intercourse. The anti-foreign party was formed. The poor were suffering from famine and the rise of prices on commodities. Popular clamor was loud against foreigners and the government [in] Yedo. Cholera also broke out and swept away thousands of men. The people thought nature and man combined in the scheme of national destruction. The Shogun’s government weakened and powerful daimios divided in their views, there was no hope of increasing national strength. At the same time, the country stood exposed to the extreme danger of foreign invasion. Under these circumstances, the chief Daimios saw the necessity of centralizing power in one sovereign in order to expell the common danger with united efforts and to promote national prosperity. They persuaded, therefore, the Shogun that he should give up his long enjoyed political power and he followed their patriotic advice. This was the immediate cause of the civil war which burst upon the country. The principal theatres of this war being confined to the north, my own province enjoyed perfect tranquility, save the military preparations were alive everywhere. I remained calm in the school and continued the course of study. Much of my time, however, was absorbed by military exercises which became universal. All men in a spite of their profession or condition, were required to serve in the army. My uncle joined a company of a few hundred soldiers sent to serve in the Imperial army. I was exceedingly devious of going with him, not as a common soldier, but as a drummer, for I had acquired by this time some skill in beating the drum. The school-boys inspired with ambition for military distinction and many of them left school and entered the army. My aspirations for literary distinctions was fortunately greater than military ambitions and I did not neglect my education. I was very cautious, however, of traveling abroad for the purpose of observing the conditions of people in different places, but I did not accomplish this object till some years after the close of the war. This desire for travel arose from the circumstance that my grandfather was a great traveler and he infused my mind with interesting ideas which he formed by observing peculiar local customs.

Scarcely a year had passed when the war was at an end. The immediate effects of the war were the Imperial Declarations. His Majesty promised the people more just and equitable government and announced them to establish foreign intercourse on a more firm basis. The Emperor proclaimed the celebrated “Five Maxims” which he and his advisors took oath to maintain and have ever since observed so far as expediency allowed them. The substance of the maxims may be expressed with the following few words: Representative government, National Unity, Liberty, Civilization and Promotion of Knowledge. Thus, his present Majesty has begun his prosperous reign with the province of liberty for the people and free intercourse with foreign nations– a reign hopeful as happy for the people at home and honorable for the nation abroad.

Shortly after the end of the war, I set out on journey for Nagasaki with the purpose of studying English, for their city was once considered the best place for learning foreign languages. On my departure, I met with difficulties. Many old-fashioned friends of mine did not indeed oppose to my going, but tried to let me change my design. My father who was then in Osaka had sagasity to foresee the importance of ac[quiring] the knowledge of one of foreign languages, the study of which has become afterwards universal throughout the Empire. He wrote to me that I should not change my design under whatever circumstances. I could not, of course, see the growing importance and usefulness of the new course of study I was about to enter and I had strong inclination to continue the study of the Classics. It was hard for me to determine whether I would take the advice of my friends or my father’s and I was wavering between the two until when I made up my mind to follow the latter’s advice at the instance of a friend of mine to do so. This friend was then in Nagasaki. He sent me a letter in which it was stated that nothing would be more foolish to take the blind advices of the old-fashioned gentlemen who knew nothing about foreigners and their countries. I started, therefore, for Nagasaki, leaving a letter to my friends with the following words– “I cannot defer, my dear friends, to your opinion on this matter, for I made up my mind to know everything about foreigners and judge them accordingly.”

After the journey of fifteen days, I arrived at Nagasaki, but to my disappointment, I found no good school there. The seat of foreign education had been already transferred to Tokio, where I am living now. The names of Kei-o-gi-juku or Fukuzawa’s private school and Kai-sei-jo were eminent. I resolved to enter one of these schools. After sojourning for a couple of months at Nagasaki, I embarked for Yokohama with a company of four friends. I spent five days for the voyage on the board of P.M.S. the N. York and arrived at the port and soon came up to the city. Having entered at once Kai-seijo, I took up for the first time the study of English. At this time, the system of instruction and mode of discipline were quite different from what they are at present. Instruction was given mostly by native tutors and we had reading lessons only once or twice a week with English or American teachers. The chief work of students consisted of translating English into Japanese and trying to understand the meaning of text and we never tried to commit to memory any important facts or [points?] in them. Such system of instruction was of course very imperfect and some improvement was necessary. By-and-by, an important reform was affected. By this reform, the curriculum of foreign colleges was introduced with the name Sei-soku in contradiction to the collegiate course in the old system which was called Hen-soku. I believe Mr. Katsuki of Saga was one of the first who proposed the plan of this reform. Thus, the new world Sei-soku and Hen-soku had their origin in Kaiseijo. Kaiseijo adopted exclusively the seisoku, while Fukuzawa was the defender of the hensoku, but lately he has changed his views and is now rather inclined to the seisoku. About this time, the study of foriegn languages became universal . The superiority of European politics, literature, philosophy, science, and arts excited admiration of those who studied anything about the subject. Translations of miscellaneous useful books by Fukuzawa, Uchida, and others, and versions of law books by Mitszkuri and others had certainly a great influence on the Japanese mind.

In the same year that there was a great change in the college, we witnessed a great political revolution. I mean the final abolition of the feudalism. Although its form had been abolished some years before, its spirit still existed in reality. Local views and feelings of local interest being still prevalent, nothing was more necessary, in order to increase [na]tional strength and to promote national prosperity, than the entire overthrow of the feudal system and consequent centralization of power. The object was accomplished by the bloodless revolution. In relation to the power of taxation, the military force and the administration of justice, government was centered in the Imperial hand. Society was also, to some extent, consolidated to form a Japanese nation. There appeared the Japanese patriotism. National interests and general ideas have ever since taken possession of every intelligent mind. By this revolution, Japan has done what European nations did in the fifteenth century. Towards the end of that century European nations began the process of centralization, and in the beginning of the sixteenth century, Europe witnessed the commencement of diplomacy, treaties, alliances and wars and the rise of international trade. Japan established more friendly intercourse with other nations when the feudality was broken down and power was centralized. Then, both in Japan and Europe centralization and foreign intercourse began at the same time. There is forever a difference between Europe of the fifteenth century and Japan. In Europe, foreign intercourse was the effect of centralization and in Japan it was the cause of centralization. For instance, England begun to interfere more regularly in foreign affairs and to establish intercourse, after the nobility was annihilated and consequently the royal power was increased. On the contrary, in Japan, foreign intercourse being once opened, centralization of power was necessary to defend the country against foreign foes and even indispensable to keep its independence. But, did England or France or any other country of the middle ages break down its feudalism without bloodshed?

In England, centralization was the result of the long wars of the Roses. In France, the feudal systems was substantially overthrown in the fourteenth century but it was not until the revolution of 1789 that the oppressive exactions entailed upon the peasantry were finally removed. In Japan, it was overthrown without any scene of bloodshed. This success is owing to the combined efforts of the people and government. Previous to the revolution, many Daimios resigned their office and surrendered their territorial rights simply from patriotic motive. These were indeed obstinate Daimios, but foreseeing their fate, they were not disposed to oppose. Letters were sent to the Great Council and memorials were presented to the Shugi-In or to deliberate assembly, advising the real centralization. The policy of the government was indeed sanctioned by the public spirit of the age.

With the political change, my mind underwent an entire revolution. I was no longer bound with local prejudices. My patriotism far from being a mere prejudice, I suffered it to be sanctioned with reason. This is the natural effect of traveling, for it gives freedom to the mind. I was still loyal to my old prince, but when he was removed from office, I rejoiced at [?] than lamented, for national patriotism was greater than loyalty to him. It is a strange thing how few foreigners can understand why so quietly the Daimios gave up their feudal rights. They say the high officers were once the subjects and Ka-ros of the Daimios and it is strange how they undertook the ruin of their masters. They can easily understand, if they remember that the officers felt patriotic emotions more deeply, as I did myself, than loyal feelings toward their former masters.

Now, I shall close my autobiography, pointing out the subjects which I promise you to write upon on a future opportunity. These are my observations in Kin-sin during the last tour over it, the change of ministry in the close of the last year, and the late outbreak in Saga.

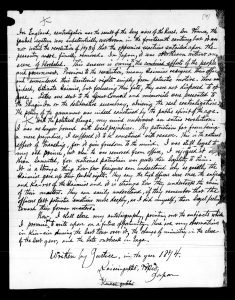

Written by Justice, in the year 1874

Kaisei-gakko, Tokio, Japan

-

KOMURA JUTARO 小村寿太郎 (1855-1911)

Born in present-day Miyazaki prefecture. Entered Daigaku Nanko in 1870. Studied Law at Harvard University as one of the first students senty by the Ministry of Education. For more information, see his biography in “People.”

-

When reading this personal autobiography written by statesman Komura Jutaro, it is evident that he grew up amongst a lot of changes happening in Japan. His whole life up until the point where he wrote his personal autobiography for Griffis’ class was constant development of Japan. When reading this autobiography, we are able to see Komura’s vision of Japan as it changes through his own eyes. Due to his different associations with multiple groups within the weakening feudal class, he is able to feel and understand each group in a particular way. Especially how he expresses his empathy for the peasant class. Because his uncle was a farmer, he would occasionally come help, and his classmates would “laugh at his low employment.” Because of these experiences, and not necessarily being a peasant, but being rather educated, he grew compassion and companionship with peasants and saw their personal struggles firsthand. This is why throughout his essay we can see his anti-feudalism attitude towards Japan’s social class status.

Komura Jutaro also expresses his compassion he has for the military, and young boys who step up to be heads of households when they are secretly minors. He talks about how they are hard working and go to school to fulfill their necessary duties to satisfy their families as well as the law within the feudal system. In addition, Komura specifically discusses how local town-boys dedicated their time of study to arithmetic, which he explains is looked down upon in Japan. Being a student himself, he learned some arithmetic himself, but discusses that regular schools (public and private) do not teach arithmetic and only classics, philosophy, Confucianism, etc. and that those who are studying arithmetic end up becoming traders. It is looked down upon in general to know how to handle money. There is a negative connotation on traders because of their greed for money and how they keep it to themselves and deceive their customers. These examples of different social classes within Japan’s system show how Komura sees the people of his country, emphasizing his disagreement and need for change in society.

Later in his autobiography, Komura Jutaro discusses how the system became overthrown and foreigners started to heavily influence the education system in Japan in creating daigaku. Because students of all different social classes were getting the same education, as well as getting the same jobs that were vital to the government system, educational system, militant system, etc; the social class divide ended up dissolving. Even though the feudal system was abolished earlier, there was always a sense of social class due to the past system being part of the masses’ lives. He writes that what Japan was experiencing now between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, is what the western countries underwent in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, minus the amount of bloodshed the west underwent to achieve this. This highlighted Komura Jutaro’s patriotism for his country as it continued to successfully develop further as the Meiji period progressed.

-

Asides from his patriotism for Japan, Jutaro’s desire for knowledge also manifests itself in agriculture and the peasantry, as he hopes technology can increase the profits of the harvest and bring about other agricultural advancements. This is interesting because Komura Jutaro connects peasant farmers, who are at the bottom of the feudal system’s hierarchy, with technological advancement, which was a very Western and in hindsight, highly regarded concept. It is this way of thinking that not only highlights Jutaro’s anti-feudal outlook, but also foreshadows the more Westernized thoughts and beliefs he later adopts. This sort of change is premeditated and shows itself during his school years, as he claims he “feels patriotic sometimes, though patriotism arising from a mere school prejudice.” In other words, rather than whole-heartedly supporting the shogunate, Jutaro seems to really only have done so because a proper citizen should support his government. And thus, Jutaro describes the course of events that occurred leading up to the downfall of the Shogunate quite objectively, as he weighs the anti-foreign attitude amongst the public against its own internal struggles. Yet his way of phrasing regarding how the Shogunate collapsed reveals a glimpse into his personal opinions, as he essentially states that the daimios’ solution for the Shogunate to retire resulted in introducing a much bigger threat than foreign enemies: civil war. And Jutaro implies that it is this war brought upon by the feudal leaders that stole the precious time he had to further pursue education. But Jutaro’s anti-feudal and pro-educational mindset seems to manifest itself yet again, as he is primarily a drummer-boy who is far from the frontlines of war. In the midst of his autobiography’s objectivity, we have another glimpse of Jutaro’s support and admiration for education, as he articulates that luckily, the weight of “literary distinctions” still prevailed over “military” distinctions. This academic priority can be attributed to the importance of Confucianism, philosophy, and other classics, even over the importance of being a warrior in samurai culture. But for Komura Jutaro, this distinction particularly meant that he could continue his studies in peace. And he is certainly able to do so under the new Emperor’s regime, as one of the new legislations, “Five Maxims”, calls for “Liberty” and the “Promotion of Knowledge.” Yet simultaneously and perhaps ironically, Jutaro still shows some resistance to the idea of exploring what lies outside of Japan, which accentuates the influence of one’s respective environment and its majority opinions on one’s own perspective. Nonetheless, the peculiar tales of his grandfather’s adventures and the mysteriousness of the foreigners entices Jutaro to leave Japan and explore new waters.

Now, Komura Jutaro’s educational journey enters a new phase, as he leaves on his quest to learn English. But before being completely committed, Jutaro once again, highlights his hesitation, as his companions back home urge him to change his reasons for traveling abroad. From his autobiography, we the readers can imagine it must have been difficult studying the Classics and other information that must seem irrelevant to bettering the nation of Japan. Only this time, it is Jutaro’s father and another friend that convinces him to stick with learning English, as the two help him realize it would truly be foolish to give into the Japanese’s baseless and preconceived prejudices about foreigners. At that moment, Jutaro notably decides to commit to learning a foreign language and the culture surrounding it. This process allows him to truly break away from the influences of the masses on his outlook while simultaneously Westernizing his views, letting his initial anti-feudal beliefs show through once again when he calls his former friends in Japan, “old-fashioned.”

-

In his autobiography, Jutaro describes his childhood being raised in a Japanese feudalist environment. He defines two distinctive periods of his life, the first marked by a feudalist childhood in a rural environment, and the second in a city life with a focus on academia. Jutaro stands out in his familiarity with different orders of the feudalist system. He has an ability to understand people who are different from him. He is able to appreciate the military rank’s sense of honor as well as students who studied arithmetic. He was able to look through societal standards and form his own opinions. Despite being ridiculed by his classmates for his status as a worker in agriculture, Jutaro is able to look over negative opinions of others and form his own opinions about the feudalist system. He also discusses patriotism and brings to question the influence of school education on patriotism and prejudice. Children were taught to fear foreign nations and encouraged to feel patriotism.

Jutaro’s curiosity is evident when he describes his decision to travel to Nagasaki study English. Despite the opposition from his father and friends, and decided to travel to Nagasaki and Yokohama in pursuit of learning English. Jutaro compares the Japanese and the Western educations systems. After finding no schools in Nagasaki, he travels to Yokohama, then Tokyo. He reflects on the education system of the time and notes that the education system had a “mode of discipline”. He disapproves of the lack of emphasis placed on learning and understanding important facts and poems. Students were asked to translate English to Japanese and learn the meaning, but did not learn factual information that they could later benefit from. He notes the importance of translated works from English to Japanese in exposing the Japanese to the English way of thinking. He also acknowledges that there was a general consensus about the “superiority of European politics, literature, philosophy, science, and arts” that made the Japanese want to learn more about European ways.

Jutaro also discusses his anti-feudalism perspective and his views on the ultimate decline of feudalism in Japan. He believes that overthrowing the feudalist system and establishing a centralized government in Japan was a necessary political change that led to a more prosperous Japan. He also seems to be proud of the Japanese people’s accomplishment of a “bloodless revolution” in which feudalism was overthrown without having to resort to war or bloodshed. He praises Japanese patriotism, and acknowledges that the Japanese were able to accomplish a state of centralization, similar to the European nations, but without war. He states that in Europe, centralization in the fifteenth century led to “diplomacy, treaties, alliance and wars, and the rise of international trade”. He also indicates that Japan’s motives for forming a more centralized government were more noble, in that a political revolution was necessary to be able to defend against foreign nations, while in Europe centralization was an effect of wars. Jutaro praises the efforts of the Japanese people and the government, and states that the Japanese were patriotic enough to surrender their territorial rights amicably, allowing for a centralized government to be established. Towards the end of his autobiography, Jutaro seems to have a shift in his views. He continues to show his deep sense of patriotism towards Japan, but admits that he has lost local prejudices that he possessed during his childhood, but continues to feel a strong sense of patriotism for Japan. Jutaro has the ability to look beyond societal beliefs and is able to form his own opinions about Japanese society, education, and politics.