Our Exhibition: Rutgers Meets Japan

Introduction

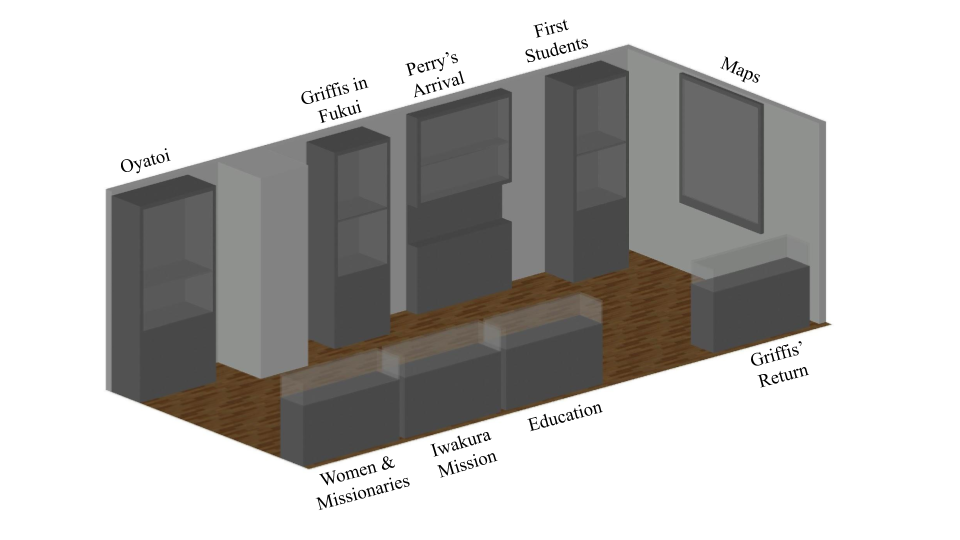

This exhibition explores Rutgers’ early relationship with Japan through the life of William E. Griffis, who entered Rutgers College in 1865. At Rutgers, he met some of the first Japanese students who came to the U.S. to study. Among them was Kusakabe Taro, a young samurai from the province of Echizen (present-day Fukui), the first foreign student to graduate from Rutgers College.

The exhibition begins with the opening of Japan to the West following the arrival of Commodore Matthew C. Perry and the “Black Ships” in 1853. The Dutch Reformed Church (later the Reformed Church of America) were among the first to send their missionaries to Japan, and in 1859, Guido Verbeck, Samuel R. Brown, and Duane B. Simmons were sent to Nagasaki and Kanagawa.

Verbeck’s school of Western studies in Nagasaki attracted students from all over Japan, and became a hub of elite youths and the future leaders of the Meiji Restoration of 1868. Some of Verbeck’s students, with the help of John Ferris, Secretary of the Board of Foreign Missions in New York, came to Rutgers Grammar School and Rutgers College to further their studies. The first were the Yokoi Brothers, nephews of Yokoi Shonan, the prominent political advisor to the Daimyo of Echizen, who arrived in 1866. Kusakabe arrived the year after. Griffis was a tutor to Kusakabe and other Japanese students, and in 1870, he was invited by Kusakabe’s home province, Echizen (Fukui), to teach Western science there. Hence, Griffis became one of the many so-called oyatoi, or American and European teachers and government advisors who had contributed to the modernization and Westernization of Japan. The journals Griffis kept in Japan and his book, Mikado’s Empire, published in 1876 after his return to the U.S. offer a glimpse into his life and experiences in Fukui and other parts of the country that he visited during his three and a half years in Japan.

Just around the time Griffis took up a new job to teach at Kaisei Gakko (later the University of Tokyo), a Japanese embassy, led by Iwakura Tomomi and other major leaders of the new Meiji Government, left for a two-year around-the-world trip to visit the Unites States and Europe with the purpose of revising the unequal treaties and gathering knowledge about the West (the “Iwakura Mission”). It is during their trip to the U.S. that they met with David Murray, Professor of Mathematics at the Rutgers College, and recruited him to help modernize the education system in Japan. Murray stayed and worked in Japan as the Superintendent of Educational Affairs from 1873- 1879.

We must remember that women, too, played an important role in Japan’s early modernization. Mary Kidder was a missionary of the Reformed Church and founded a school for girls in Yokohama, which later become Ferris Girls’ School, named after John Ferris. Both David Murray and his colleague Tanaka Fujimaro believed in the importance of educating women, and established schools for training female teachers. Griffis’ sister, Margaret C. Griffis, taught at one such school, the Tokyo Government Girls’ School.

After his return to the U.S., Griffis published numerous articles and books on Japan and offered countless lectures to introduce Japan to the Western world. In 1926, a year before his death, he was invited to visit Fukui with his wife and was awarded the Order of the Rising Sun by the Emperor. The bond between Rutgers and Japan initiated by Griffis and the Japanese students in New Brunswick lives on today, after 150 years, through the partnership of Rutgers and the University of Fukui and the sister-city relationship between New Brunswick and Fukui.

*Don’t forget to check out our interactive map of New Brunswick, Yokohama & Tokyo, and Fukui!