Fukui

by Izzy Bonvini

Fukui is a prefecture that holds a significant place in the relationship between Rutgers University and Japan. This is where, in 1867, Rutgers’ first foreign student from Japan, Kusakabe Taro, came from. In 1870, the Prince of Echizen invited William E. Griffis to travel to Japan to teach in Fukui. He was charged with the responsibility of developing a natural sciences program there that would hopefully translate to a larger-scale standard for learning and a national department of education. He agreed to the job and embarked on a journey that would change Griffis’ life and the lives of those in Fukui forever.

On March 4, 1871, Griffis arrived in Fukui and was less than impressed. He found it to be much less grandiose than he was anticipating, and was disappointed by what was in front of him.

“There were no spires, golden-vaned; no massive pediments, facades, or grand buildings such as strike the eye on beholding a city in the Western world. [He] had formed some conception of Fukui while in America: something vaguely grand, mistily imposing – I knew not what. I now saw simply a dark, vast array of low-roofed houses, colossal temples, gables, castle-towers, tufts of bamboo, and groves of trees. This was Fukui” (Griffis, The Mikado’s Empire, 423-424).

Yet by the time he left on January 22, 1872, Fukui and its residents held a special place in Griffis’ life. He found his students to be voracious learners, got along well with the officials of the domain, and was treated with the utmost respect by the people he encountered there. As he later moved to Tokyo and taught at the newly found university there, his contributions made a profound impact to the modernization of education for Japan as a whole.

Today, Griffis’ experiences in Fukui are memorialized in the relationship between Rutgers University and the University of Fukui. Together, the two university libraries have compiled their collections of documents from his time there, and continue to honor his work through their efforts.

Image Gallery:

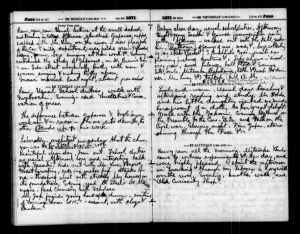

Above are a few excerpts from Griffis’ Fukui Journal. Through these entries we get a glimpse into Griffis’ daily life in Japan in June 1872. He notes the weather, what he taught at which schools on any given day, and the more intimate details of his conversations and whereabouts. In the entry from Friday, June 16, Griffis mentions making a doll for the daughter of a visitor he had at his home, and taking an evening walk with a colleague to discuss the United States Constitution and Civil War.

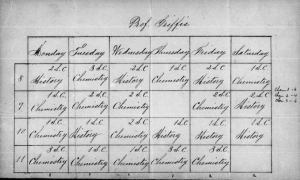

This is a copy of Griffis’ schedule of classes. After teaching Kusakabe Taro (a student from Fukui) in New Brunswick, he was invited by the Prince of Echizen to organize a scientific school in Fukui. In return, they would pay his salary, build him a European-style house there, and return him safely to Yokohama after three years. Once there, he taught physical sciences under the American principle to Japanese students. This schedule provides us with a look at how his teaching was organized on a daily basis, and what exactly he taught.

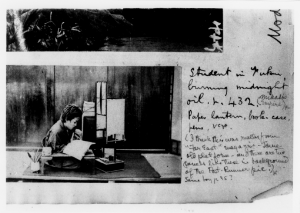

This is a photo of a student in Fukui studying into the late hours of the night. It is captioned “student in Fukui burning midnight oil.” While we might not be able to know much about the identity of this student in particular, we can use this image to deduce the impact that education had on his Japanese students, and have a better understanding of Griffis’ appreciation for their passion. In The Mikado’s Empire he writes about how he arrived to find students already hard at work, and in many of their own essays, his students included that they worked late into the night.

In this article, Griffis explains how he was offered a job teaching in Japan, and what his life was like once he got to Fukui. He mentions that there was no national department of education, and how he went there to help modernize their knowledge of physical sciences and provide a Western insight to students there. Griffis also explains how the school that he taught in was located in a palace that was formerly occupied by the Baron of Echizen. The purpose of this article was to provide context of life as an American teaching overseas, but it also translates to the audience the greater purpose of his work in Fukui.

Griffis was invited to Fukui by Matsudaira Yoshinaga, former daimyo of Fukui. They had a dinner in Tokyo, detailed in The Mikado’s Empire, where the ex-prince of Echizen invited Griffis to his yashiki, or daimyo estate. Above is a picture of the family of Matsudaira Yoshitami, taken in 1915. Yoshitami was the son of Matsudaira Shungaku Yoshinaga. Yoshitami is described by Griffis as a “sprightly, laughing little fellow, four or five years old, with snapping eyes full of fun, and as lively as an American boy” (Griffis, The Mikado’s Empire 429). The pair got along very well, and they continued to meet up in Fukui, and later, in Tokyo.

This article was written by Griffis to depict the kind treatment he was given in Fukui, as well as to take note of the small quirks and societal differences between Japan and America. He uses personal anecdotes to paint a real picture of a Japanese landscape and people, and promotes the idea of community in the foreign land, despite the extreme differences. In one story, he mentions how he had been in Fukui for a week when he started hearing local boys singing “Shoo Fly,” thinking it was the American national anthem. These stories provided a more humanizing look at the Japanese for American audiences.

In this image, Griffis is pictured with the members of class in Fukui with whom he traveled to Tokyo at the end of his residency. In The Mikado’s Empire, he noted how impressed he was with his students. They were all very eager to learn, and most nights he even hosted students, officials, and regular citizens at his house to have further lectures on a variety of subjects. These subjects included but were not limited to physical and descriptive geography, chemistry, physiology, the science of government, the history of European countries, and for a few students, the Christian religion.

Griffis’ home in Fukui was built for him as part of his deal to teach there. It was built in the European style so he was comfortable, and though the original structure (seen on the left) no longer stands, a replica was rebuilt (seen to the right) that is still used today as a way for visitors to Fukui to get a look at the way Griffis lived.

-

Fukui Scrapbook 1871 [1871-1874]. 1871-1874. Government Papers. The

National Archives, Kew. Research Source. Web. May 07, 2020

<http://www.researchsource.amdigital.co.uk.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/

Documents/Details/JTW_Part3_Reel42_Vol1>.

Griffis’s Fukui Journal 1871-1877. 1871-1877. Government Papers. The

National Archives, Kew. Research Source. Web. May 07, 2020.

<http://www.researchsource.amdigital.co.uk.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/

Documents/Details/JWE_Part2_Reel21_Vol9>.

Published works by W. E. Griffis: Kraft-bound articles from ‘American makers

of the new Japan’ to ‘Little Jo-Ji’s dream.–Travels on a purple cloud: A

Japanese nursery story’. 1872-1927.

Government Papers. The National Archives, Kew. Research Source. Web.

May 07, 2020

<http://www.researchsource.amdigital.co.uk.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/Documents/Details/JWE_Part5_Reel75_Vol1>.

The Mikado’s Empire. 1877. Government Papers. The National Archives, Kew. Research Source. Web. May 07, 2020

<http://www.researchsource.amdigital.co.uk.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/Documents/Details/JWE_Part5_Reel81_Vol1>.