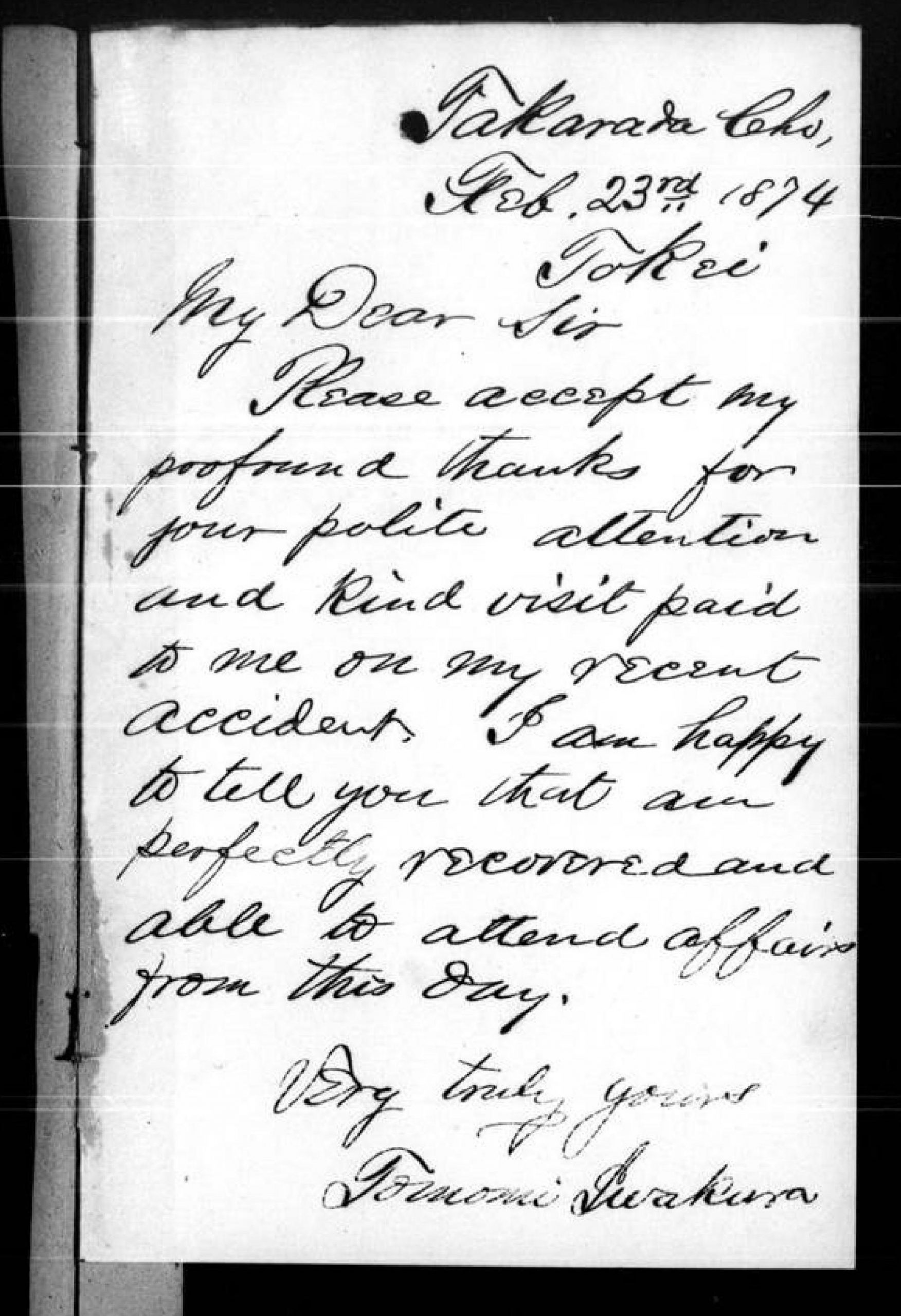

Letter from Iwakura Tomomi to William Elliot Griffis, Feb. 23 1874. This letter was sent to Griffis by Iwakura Tomomi, a prominent Japanese aristocrat and leader of the Iwakura Mission. Griffis had become connected to Iwakura Tomomi through his sons that had attended Rutgers while Griffis was attending. In the letter Iwakura thanks Griffis for visiting him following some kind of accident that he experienced, but he assures Griffis of his full recovery.

Oyatoi: The Rutgers Connection in Japanese Education

By Evan Feldman(’22) and Stephen Hu(’23)

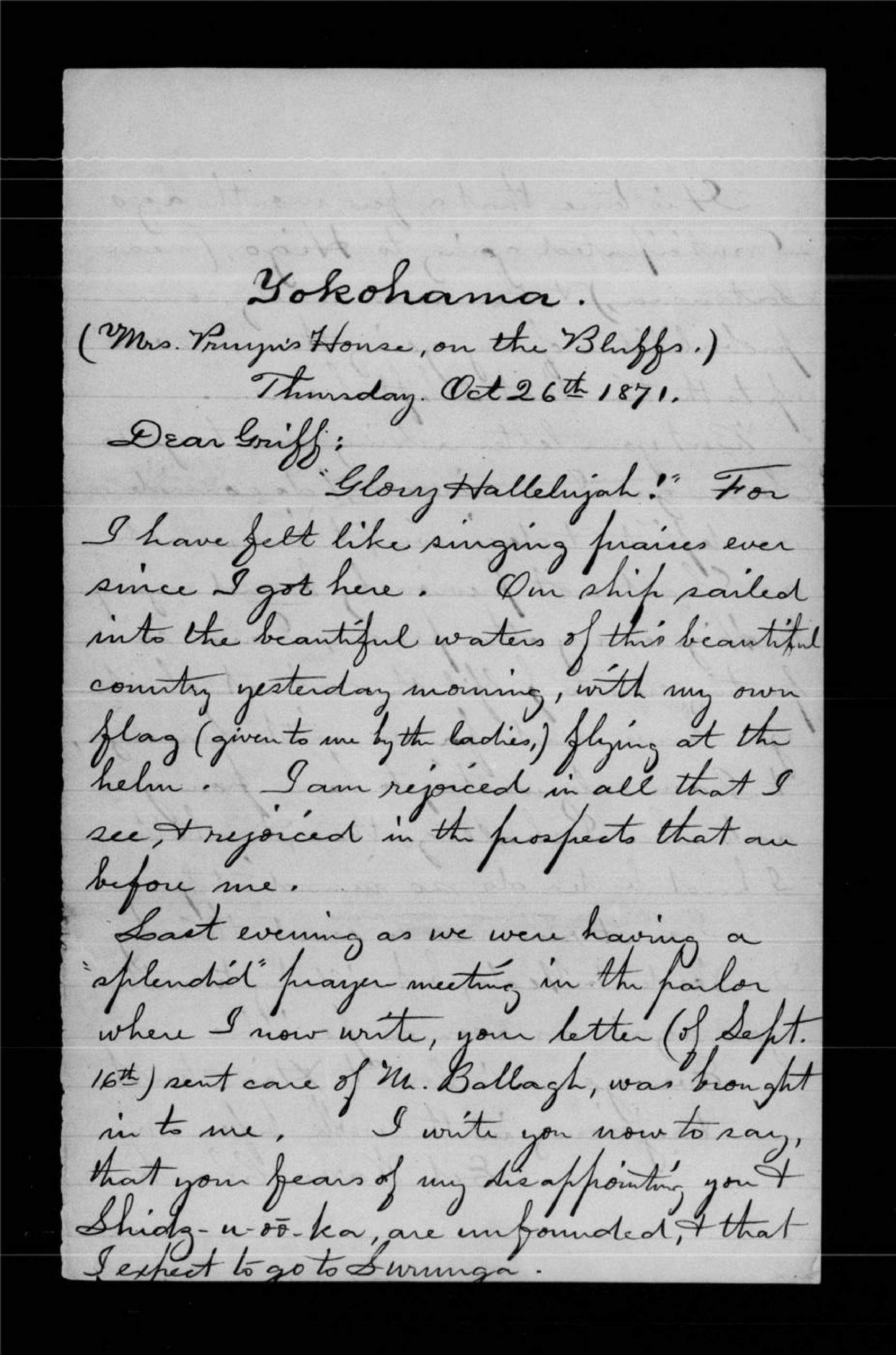

Early Meiji Period Japan had lofty goals for revolutionizing their system of education, and they drew from Western educators across the world in order to aid them in making these changes. Known as “oyatoi”, these individuals were foreign teachers and officials that played a significant role in modernizing the Japanese system of education. Networks that were built at Rutgers College between early Japanese students and professors led to people such as Dr. David Murray to become top-level education officials. William Griffis’s strong relationship with Kusakabe Taro likely influenced him to begin his career in Japan as well. In addition to these prominent Rutgers oyatoi, Edward Warren Clark and Martin Wyckoff were two other Rutgers alumni who dedicated their teaching skills to Japan.

The Oyatoi’s connection to Rutgers College was strong, but there was also an array of other Western teachers drawn from other universities and nations. This included the American scientist Edward Morse, and Lafcadio Hearn of American and Greek decent. Japan drew on a large network of talent from around the world to reach their educational goals, and because of this we are left with a variety of unique sketches, letters, and writings that account for the experiences of these oyatoi. These pieces aim to capture a glimpse into the perspectives of the oyatoi, their impact on Japanese students, and the network that brought them to Japan.

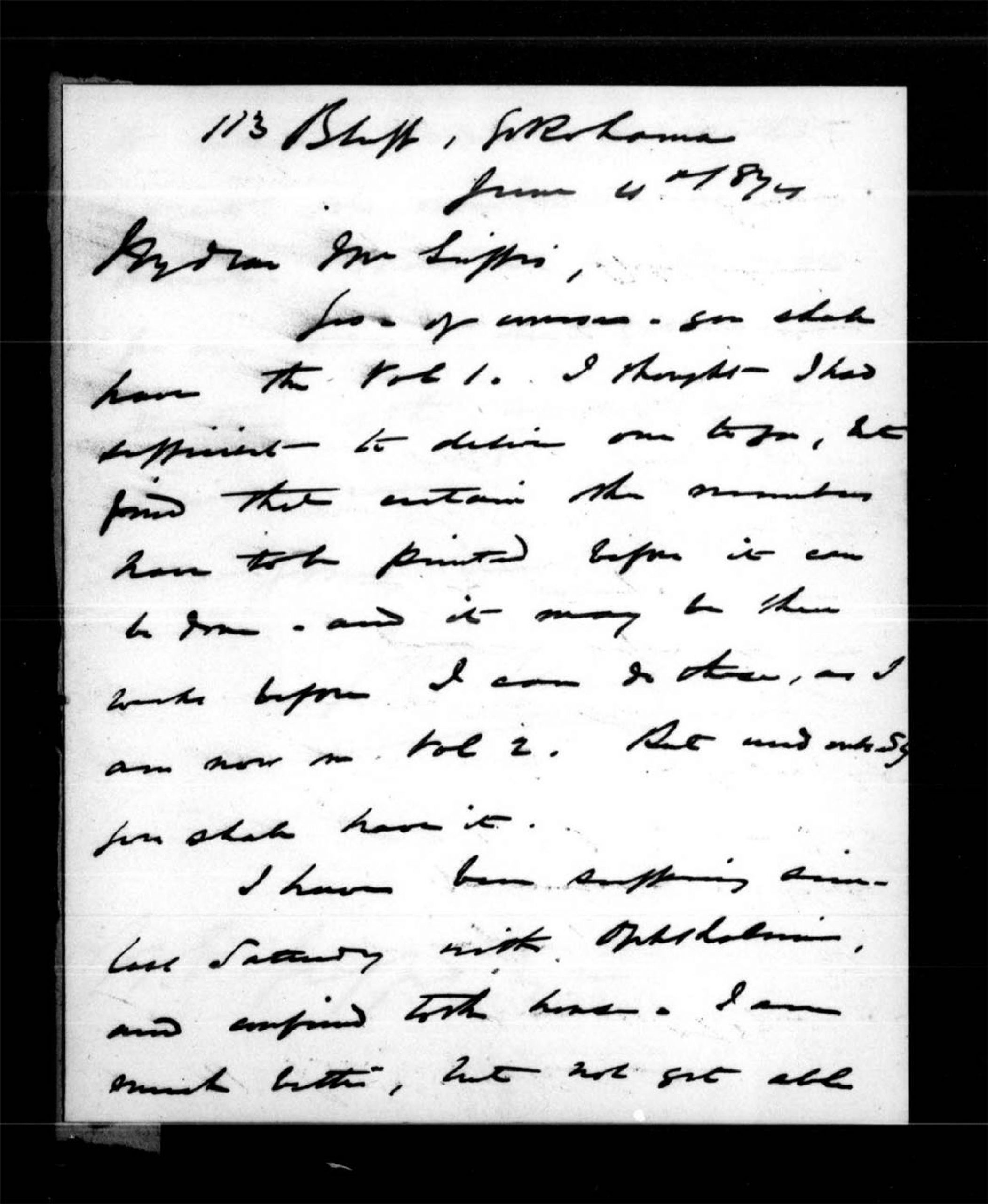

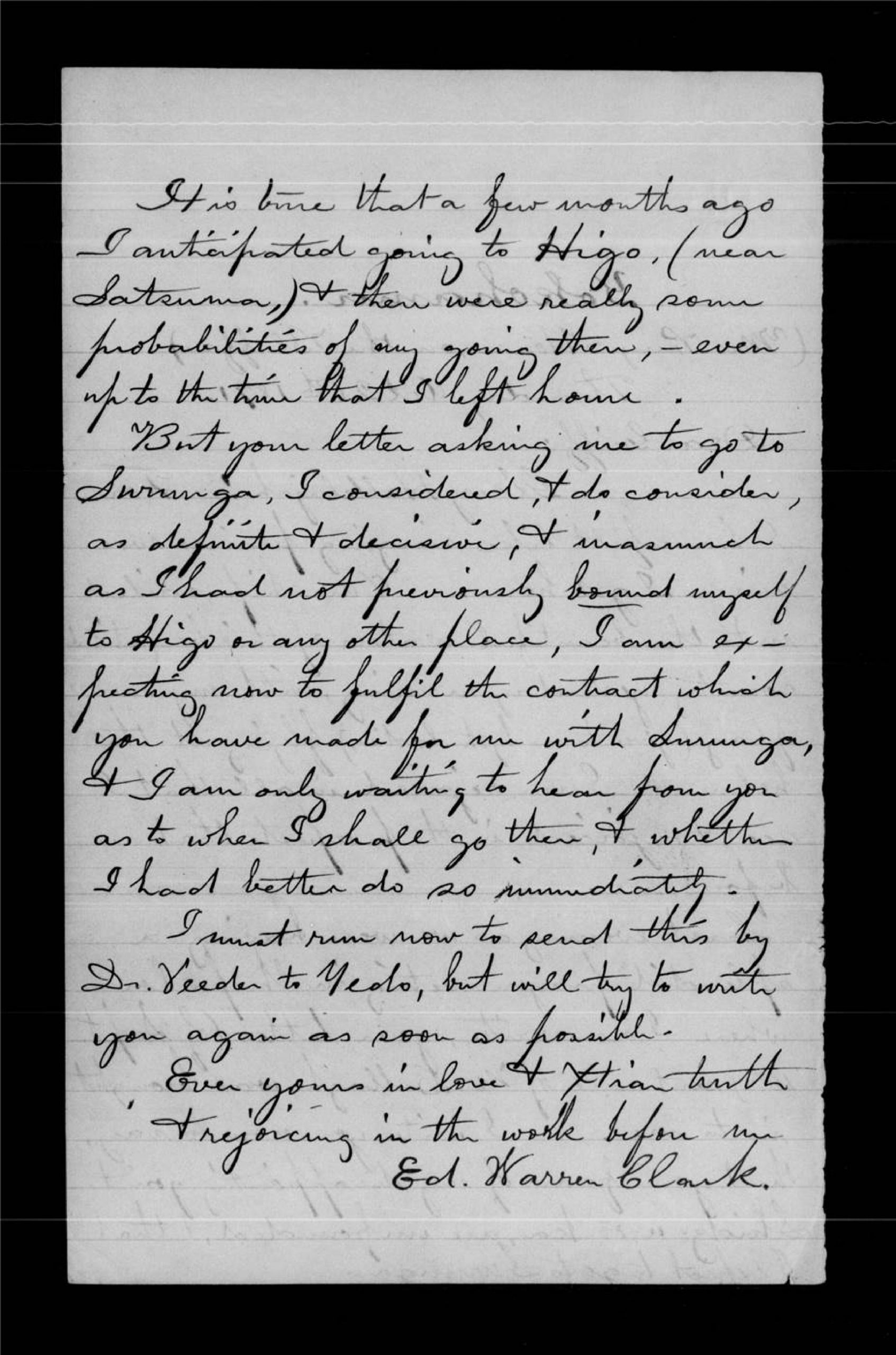

Letter From David Murray to William Elliot Griffis, June 4, 1874. This letter is expressing thanks towards Griffis for his work in Japan. At the time, Griffis was about to conclude his stay in Japan, and Murray had recently been appointed as the Superintendent of Education in the Empire of Japan.

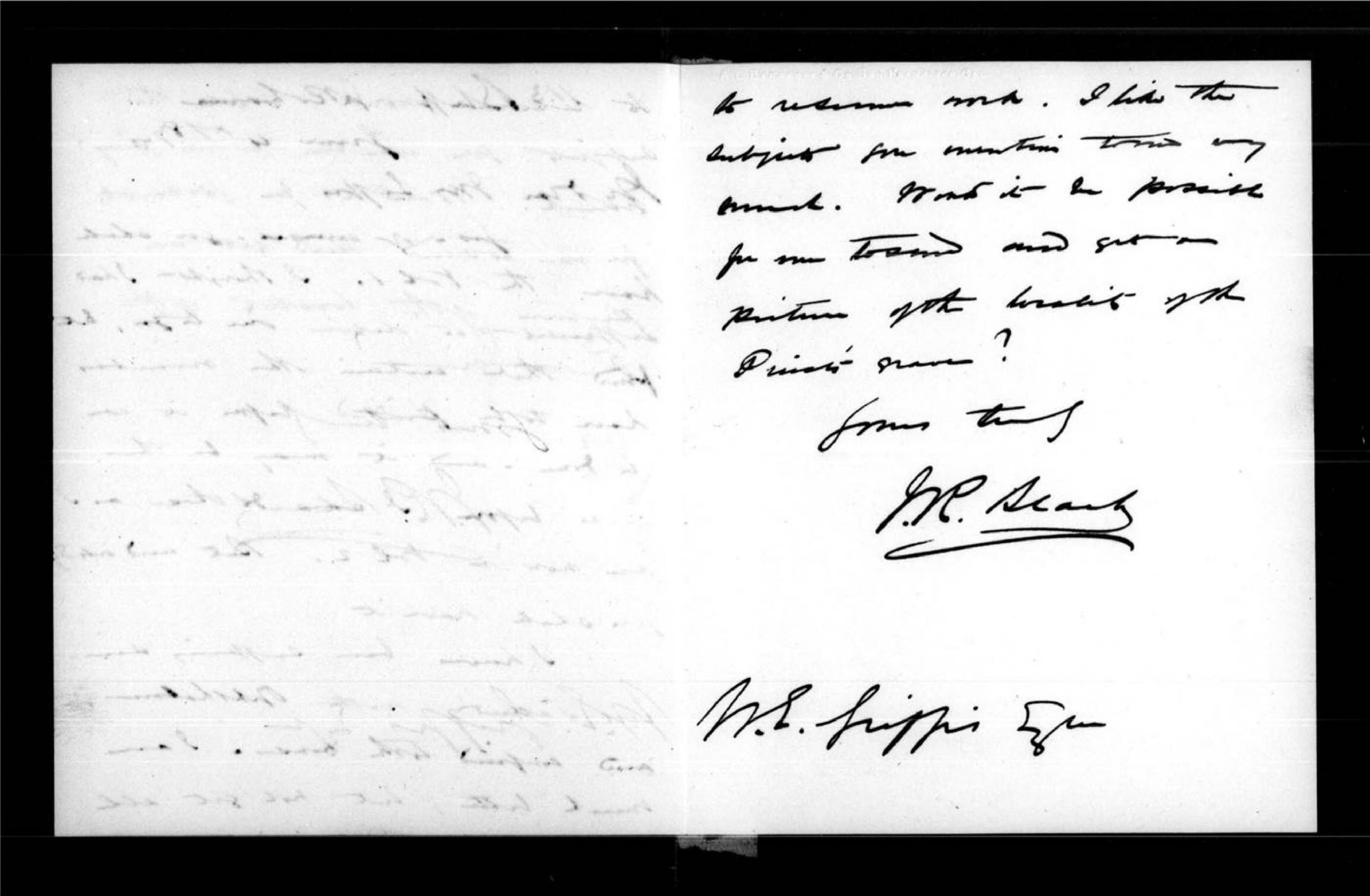

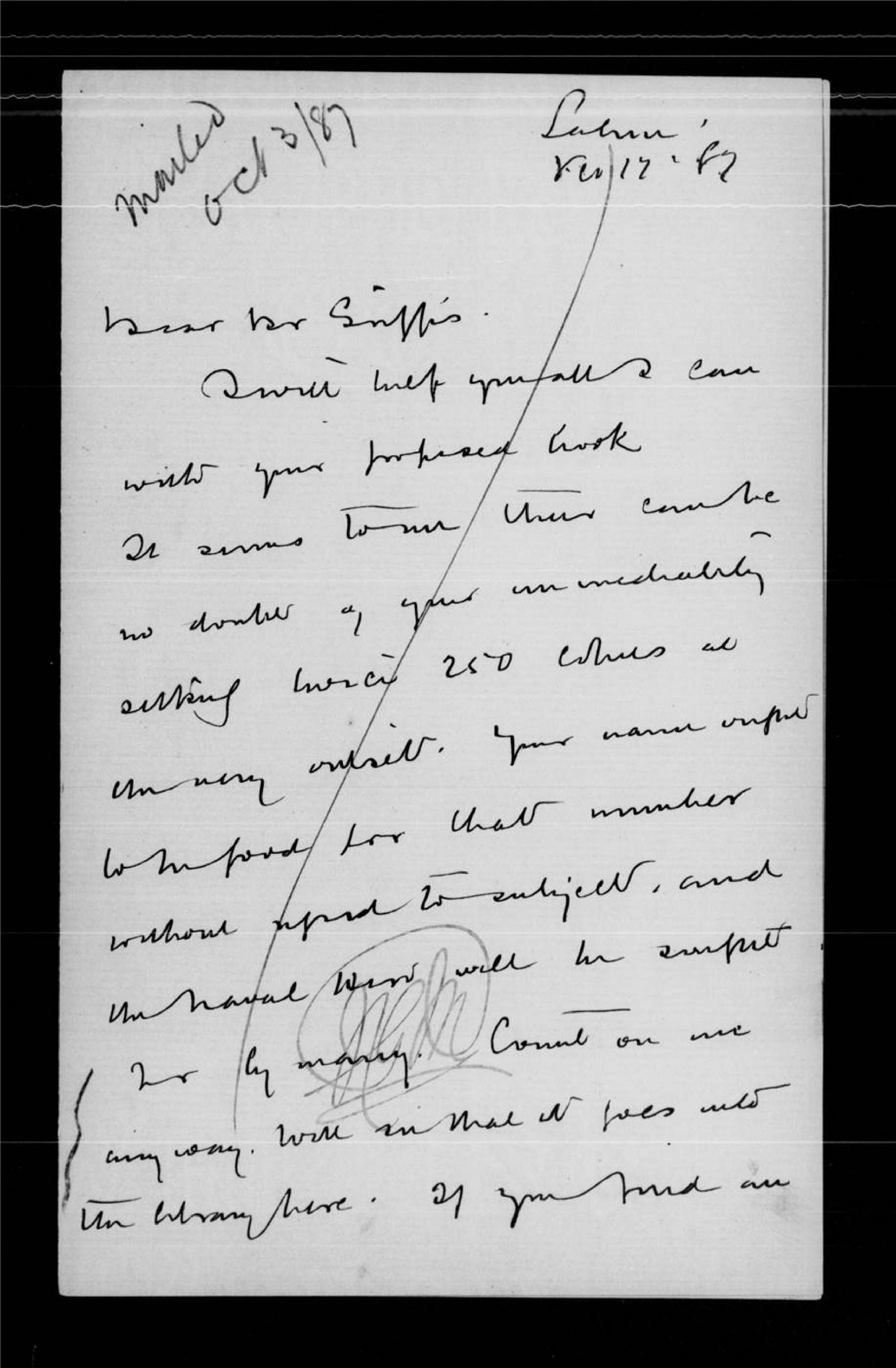

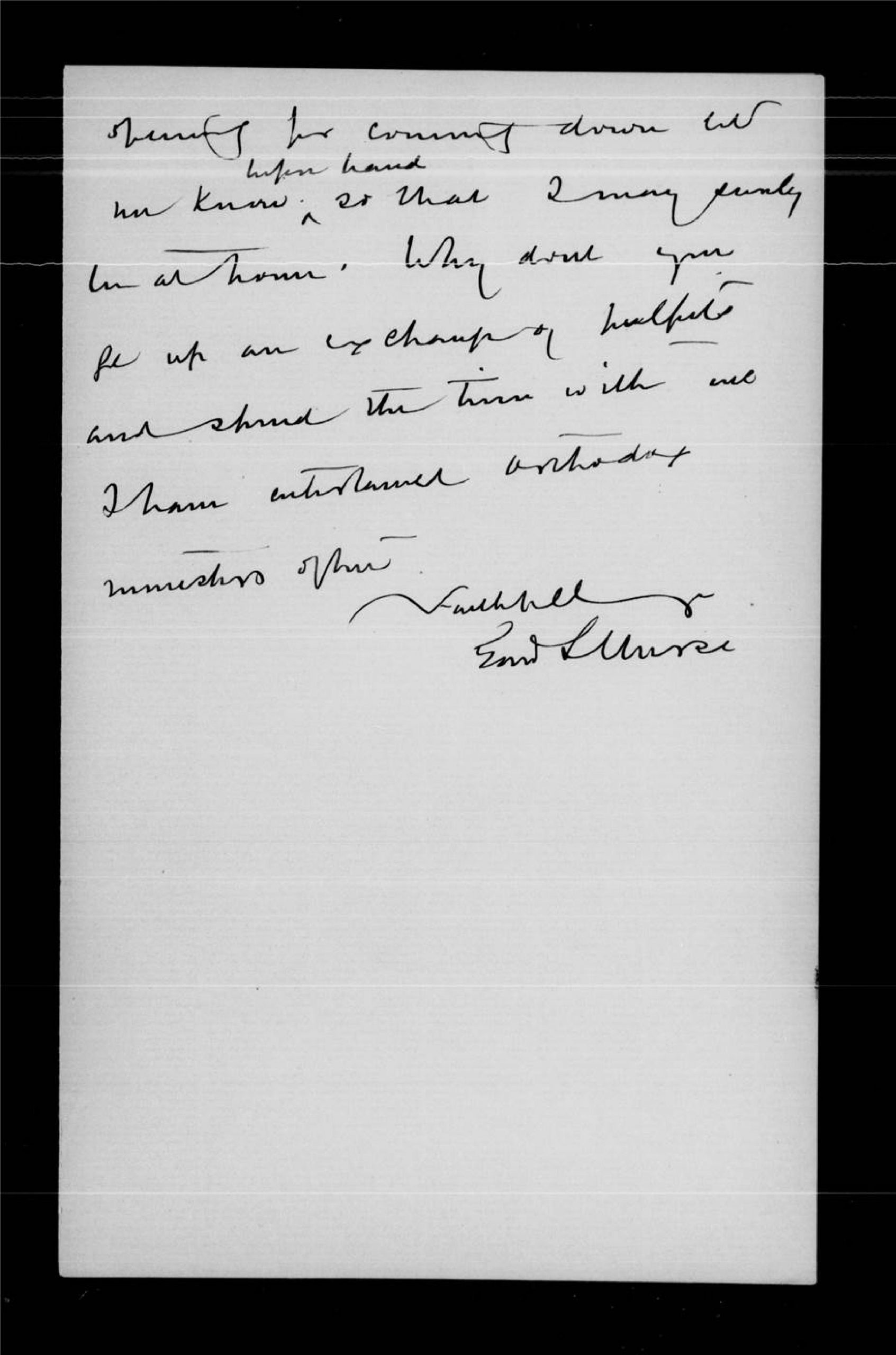

Letter From Edward Morse to William Elliot Griffis, Oct. 3, 1887. Edward Morse was a distinguished scientist and professor at Tokyo Imperial University. This letter was sent years after Griffis was in Japan, but it highlights that there was a connection between the two men. Morse commends Griffis for his work and asks Griffis to let him know beforehand if he is going to visit in the future.

Letter From Edward Morse to William Elliot Griffis, Oct. 3, 1887. Edward Morse was a distinguished scientist and professor at Tokyo Imperial University. This letter was sent years after Griffis was in Japan, but it highlights that there was a connection between the two men. Morse commends Griffis for his work and asks Griffis to let him know beforehand if he is going to visit in the future.

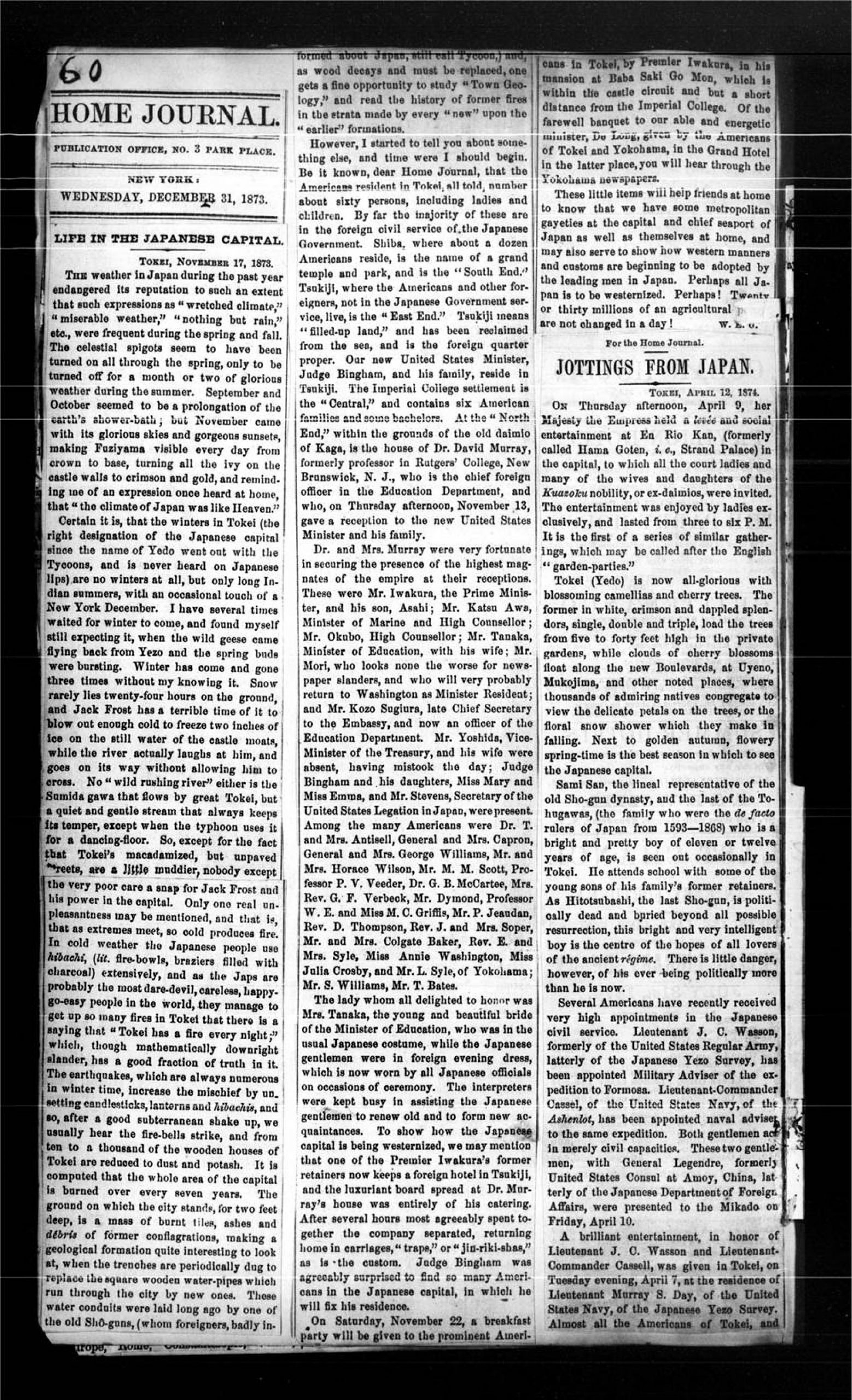

Life in the Japanese Capital, by William Elliot Griffis. This article was written for the Home Journal in New York, and provides an intriguing account of a party at the home of David Murray in which Griffis was in attendance. The list of attendants includes several notable figures such as Tanaka Fujimaro, Iwakura Tomomi and his son Asahi, Mori Arinori, and Katsu Awa. Griffis also discusses the climate difference in Japan and how he believes the Japanese are beginning to adopt American manners.

Education Newspaper Article, unknown author. This newspaper clipping is one of many that Griffis collected over the years, and it recounts a lecture he gave on Japan upon returning to the United States, at a conference on education. It briefly details the topics he discussed, which includes the way that he felt as a foreigner in Japan, and the growth he witnessed in Yokohama while he was there. His speech appeared to be based off of his book, The Mikado’s Empire, as it contained many similar themes, and even more specific details such as the fact that he carried a Smith and Wesson revolver with him while in Japan.

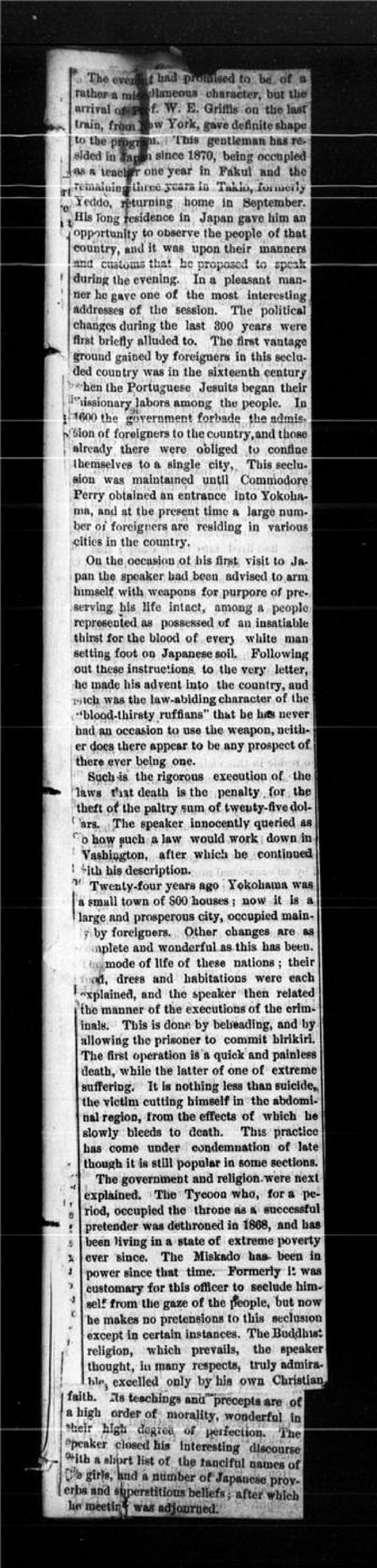

Griffis with His Students, 1874. Griffis cared deeply for his students, and he saved the photographs he took with them in his scrapbooks. This photograph depicts a science class that he taught in 1874, Griffis pictured in center.

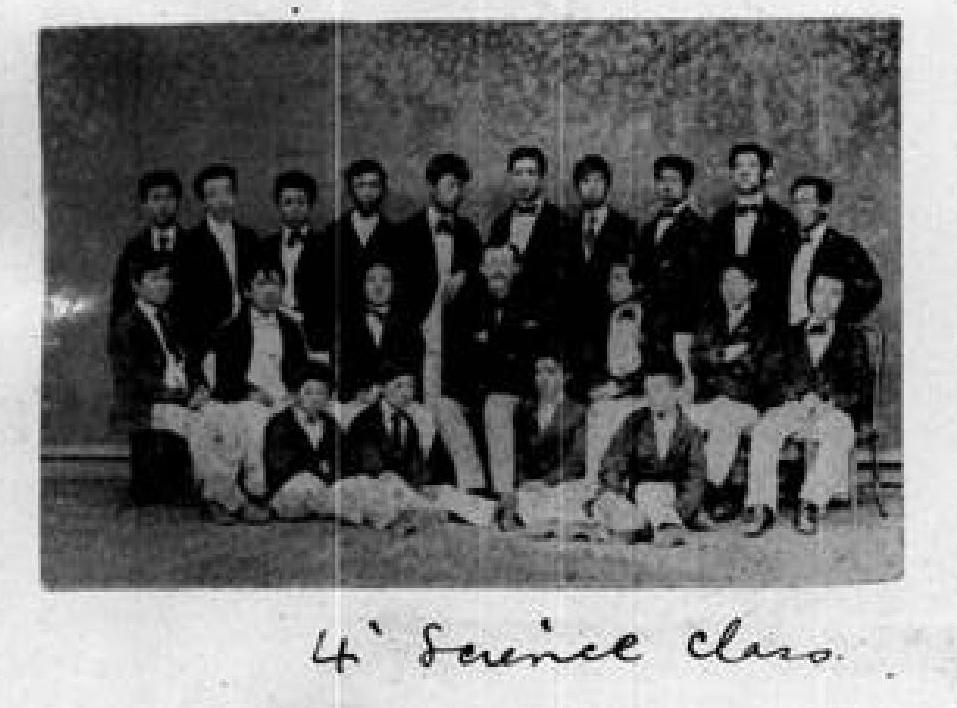

“A Story of a Fox”, Takamatsu. Griffis was more than a teacher to his students, as he was a student of Japan, and his students aided him in his learning. Griffis’s student’s essays are one of the greatest resources Griffis had to learn about Japan, as the prompts he gave varied from Japanese history to Japanese myths. This essay by Takamatsu is on a Japanese mythological tale, and it is one of the hundreds that Griffis collected over his career.

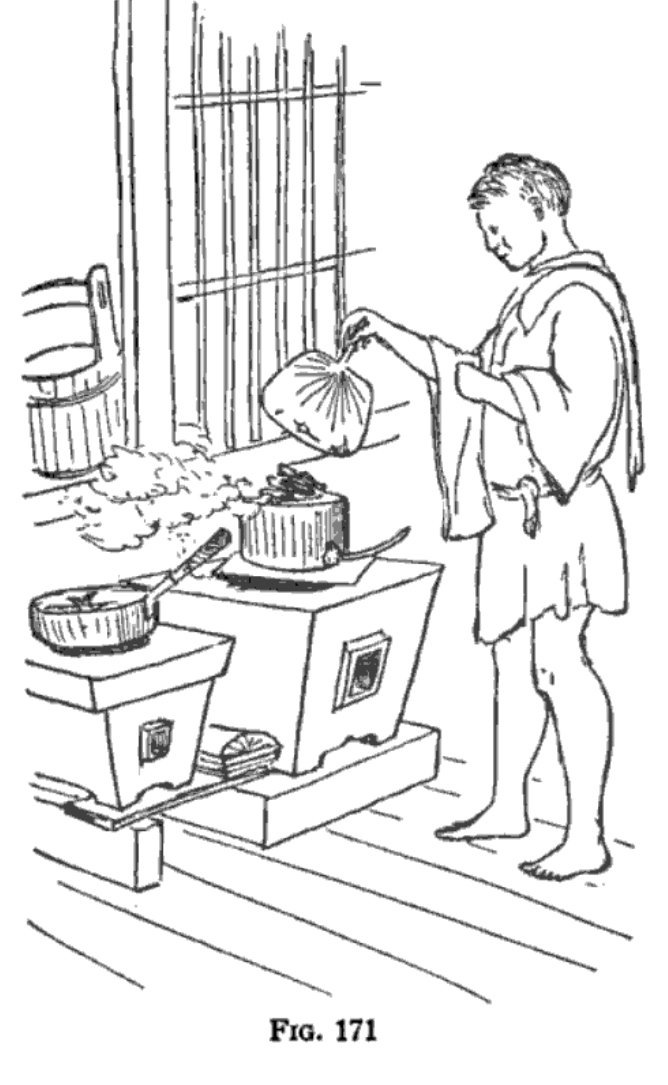

A Sketch from Morse’s “Japan Day by Day.” Edward Morse was a scientist by trade, but he became increasingly fascinated by Japanese life during his time there. He composed two books, Japan Day by Day and Japanese Homes and their Surroundings during his life. This sketch depicts a Japanese person cooking a meal. He captured everyday moments and intricacies of Japanese life, and also collected a large amount of everyday Japanese items. His collection is now contained at the Peabody Museum in Salem, MA.

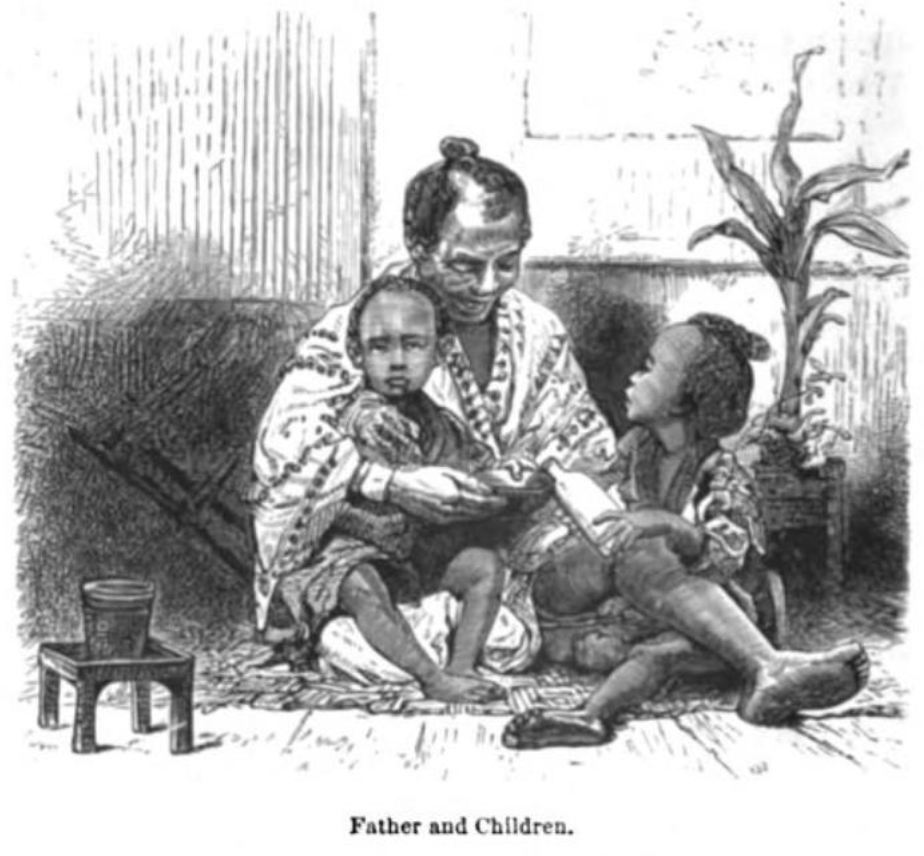

A Sketch from Griffis’s “The Mikado’s Empire.” Griffis also took time to visualize the details of Japanese life. Although he hired an artist to complete his sketches for him, they depict many aspects of Japanese culture and lifestyle. in contrast to Morse’s sketches, those of Griffis are more sophisticated while generally capturing similar moments. The image above depicts a father holding his children, and is contained inside of Griffis’s seminal work, The Mikado’s Empire.”

Works Cited:

Correspondence, Japan: B 1872-1875 – Clement, Ernest 1893-1899. 1871-1928. Government Papers. The National Archives, Kew. Research Source. Web. May 03, 2020. <http://www.researchsource.amdigital.co.uk.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/Documents/Details/JTWE_Part3_Reel28_Vol1>.

Correspondence, Japan: Kozai 1927 – Mudgett, E. H. 1872. 1870-1928. Government Papers. The National Archives, Kew. Research Source. Web. May 03, 2020. <http://www.researchsource.amdigital.co.uk.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/Documents/Details/JTWE_Part3_Reel33_Vol1>.

Griffis, William Elliot. The Mikado’s Empire. United States, Harper, 1876.

Morse, Edward. Japan Day by Day. Houghton Mifflin Company. 1917.

Scrapbook: Margaret Clark Griffis to Japan & William Elliott Griffis in Tokyo, 1872-1874. 1872-1874. Government Papers. The National Archives, Kew. Research Source. Web. May 02, 2020. <http://www.researchsource.amdigital.co.uk.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/Documents/Details/JTWE_Part3_Reel42_Vol3>.

Student Essays: 1-199. Government Papers. The National Archives, Kew. Research Source. Web. May 03, 2020. <http://www.researchsource.amdigital.co.uk.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/Documents/Details/JTWE_Part2_Reel25_Vol1>.

Tokio Scrapbrook 1872-1880. 1872-1880. Government Papers. The National Archives, Kew. Research Source. Web. May 03, 2020. <http://www.researchsource.amdigital.co.uk.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/Documents/Details/JTWE_Part3_Reel42_Vol4>.