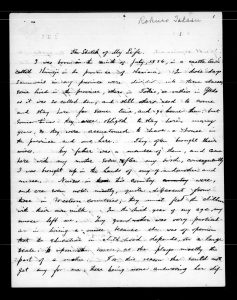

Rokuro Takasu

The Sketch of My Life

(Transcribed by Priya Agarwal and Shannon Hiner)

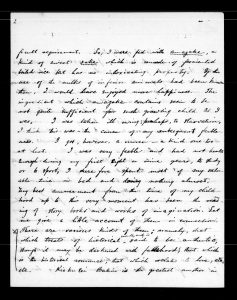

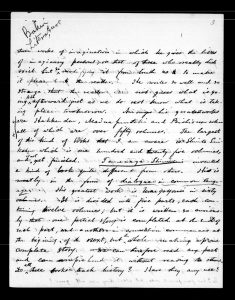

I was born on the ninth of July, 1856, in a castle town called Himenji in the province of Harima. In those days samurais in my province were divided into three classes; some lived in the province, others in Tokio, or rather in the Yedo as it was so called then, and still others used to come and stay here for some time, and go home then: but sometimes they were obliged to stay here many years, so they were accustomed to have a home in the province and one here. They often brought their wives. My father was a member of them, and came here with my mother soon after my birth, consequently I was brought up in the hands of my grandmother and nurse. Nurses in this country were, and are even now mostly, quite different from those in Western countries; they must feed the children with their own milk. In the third year of my age, my nurse left me. My grandmother was very particular in hiring a nurse because she was of opinion that the education in childhood depends, on a large scale, upon the nurse, and she plays mostly the part of a mother. For this reason she could not get any for me, there being none answering her difficult requirement. So, I was fed with amazake, a kind of sweet sake which is made of fermented boiled rice but has no intoxicating property. If the use of the milks of inferior animals had been known then, I would have enjoyed more happiness. The ingredients which amazake contains seem to be not quite sufficient for such growing child as I was. I was taken ill owing; perhaps, to starvation. I think this was the cause of my subsequent feebleness. I got, however, a nurse–a kind one too–at last. I was very feeble and had not health enough during my first eight or nine years, to study or to sport, I therefore spent most of my valuable time in bed and doing nothing almost. My best amusement from the time of my childhood up to this very moment has been the reading of story books and works of imagination. Let me give a little account of them in connection. There are various kinds of them; namely that which treats of historical events, and is said to be authentic, though it may be darkened with falsehood; that which is the historical romance, that which relates to love, etc. etc. Kiokutei Bakin is the greatest author in these works of imagination in which he gives the lives of imaginary persons, or that of those who really did exist but so modifying it from truth as to make it pleasant to its reader. He writes so well and so strange that the reader can not guess what is going to be afterward just as we do not know what is taking place tomorrow. [Among?] his greatest works are Hakkenden, Asahina Juntoki and Bishionenroku all of which are over fifty volumes. The largest of this kind of books that I am aware is Shinto Suikoden which is one hundred and twenty-five volumes, and is not yet finished. Tamenaga Shunsui invented a kind of book quite different from others. His is mostly in the form of dialogue in common language. His greatest work is Umegoyomi in sixty volumes. It is divided into five parts, each containing twelve volumes; but it is written so curiously that one partial story is completed at the end of each part, and another in continuation commences at the beginning of the next, but the whole making up one complete story. We can therefore read any part and can comprehend it without reading others. Do all these books teach history? Have they any use? Are they for mere amusement? No, they are not only for mere amusement, but at the same time for something else. What is that something? It is the improvement of morality. In them all, good people may suffer at first but prosper afterward; And wicked do the reverse. Well, I will not stop boring giving the sketch of story books instead of giving mine.

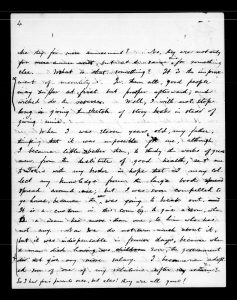

When I was eleven years old, my father, thinking that it was impossible for me, although I became little better then, to study the works of great men from the destitute of good health, sent me to Tokio with my brother in hope that I may collect my knowledge from the large book spread around me; but I was soon compelled to go home, because the war was going to break out. It is a custom in this country to give a son, when a man has more than one, to him who has not any. Now we do not care much about it, but it was indispensable in former days, because when a man died having no son, the government did not give any more salary. I became an adopted son of one of my relatives after my return. So I had four parents once, but alas! They are all gone!

So the Daimio of my province was a Tokugawa party, all the Daimios in adjacency made an assault and besieged the castle; but there were only a few ready soldiers in the castle, most of them being in Tokio with the Daimio, and moreover no Tokugawa party was near us whence we can obtain assistance, we surrendered leaving the castle. I being young and unable to fight, I escaped the castle with my family, after the first engagement, to a mountain village.

The samurais of higher rank lived in the castle, as most of the Daimios did in that of Tokio. My house was situated not over one hundred yards from the place whence the enemy was discharging. As I was looking out from the window, I saw the tiles of the castle–gate flew about, when cannon-balls struck them, just as the leaves of trees do when winds blow against them, large balls flew over my head with hissing noise, and shells broke with loud report all the time the thundering sound of cannon and crackling noise of muskets accompanying it; it was fearful sight! This was the first time I stood before cannons and muskets, and I hope this will be the last!

In the twelfth year of my age, as I surmounted great deal my bad health, my brother persuaded me to study a foreign language and therefrom to obtain some knowledge of foreign lands, because he thought it was absolutely necessary for us to do so, but he supposed he was too old to begin it. I went to the school of Mr. [Ga?] where I commenced the study of English language. I considered, however, it was very dull to learn spelling, conversation, and the like, so I spent most of the time in playing, thus I got very a little knowledge of the language, though I studied and played almost half a year, when I was compelled to go home.

Some obstinate officers who believed in the ascetic opinion of the Chinese that all the other nation except the Japanese and Chinese were savages, declared that we should not study the language of savages, because there was no advantage, but on the contrary there was disadvantage which was that if we should study it, we should be liable to become Christians, which they we are very much afraid of. One of my friends told me that we must necessary study English, and then I must be very patient, because the further we know the language the more interesting it becomes, though it might be dull at first; and he remonstrated with the officers and I was permitted to come to Tokio at last. I entered the private school under the care of Mr. Fukuchi; but to my sorrow all the knowledge which I got in Osaka was almost entirely lost. I therefore attempted to get it back by hard-working. I studied during the night and slept during the day, because I thought it was the best means to prevent disturbance. A few months I passed in that way, but at last I noticed that after reading about two hours, my eyes became hazy and it grew worse and worse. I asked a doctor to make some operation upon them. I doubt if he was a quack doctor; and ever since that time, I have become near sighted and the inseparable friend with the spectacles. In the latter part of my thirteenth year I entered this school. Since then my life has been very simple and regular comparatively, and there is nothing particular to be recorded.

Rokuro Takasu

-

TAKASU ROKURO 高須碌郎

One of the first nine students of the School of Chemistry of Kaisei Gakko. He became the first graduate of the Chemistry Department, Faculty of Science, University of Tokyo, in 1877. He served the Ministry of Education.Also read his “My First Impressions of Foreigners.” -

Reading Takasu’s autobiographical essay was extremely enlightening, especially after reading his essay on his impressions of foreigners. I was familiar with his handwriting, and his message was able to convey across hundreds of years. To start, Takasu describes the time when he was a baby. I was shocked to learn that many Japanese children have wet nurses who breastfeed them. I wonder if this is an indication of the wealth of Takasu’s family. He goes on to explain that his family was unable to find him such a nurse because “there [were] none answering” the “difficult requirement” of his grandmother’s demands. Therefore, he was fed with “amazake”. Takasu believes his ill health as a child is due to the lack of proper milk, and this is certainly a possibility because “fermented boiled rice” doesn’t seem like it would have the necessary nutrition for a child. Takasu then goes on in great length to describe the works of various authors which he enjoys. I can tell by reading this section that he has a great passion for literature and stories. This makes sense because I imagine that a child in feeble health likely wasn’t able to go out and play much, so he probably had to satisfy himself through literature and imagination. Takasu then describes an interesting part of Japanese culture wherein he was adopted by a relative’s family because they had no sons and his father had two. He explains that “when a man died having no son, the government did not give any more salary”. This, therefore, explains why such adoption would occur. Takasu does not go into depth about his feelings about this, so I wonder if he felt abandoned. He then goes on to describe how his castle, a member of the Tokugawa party, is brutally overthrown. His family has to escape and watches cannons and muskets wreak havoc. Once again, Takasu does not explain how this made him feel. However, I can’t imagine how horrifying it must be to watch your livelihood destroyed. Finally, he discusses how he has come to study English. He studied so hard that his eyes became near-sighted. This, to me, shows that Takasu is very dedicated to his pursuits. His English in this essay, while not perfect, is completely understandable. That is a testament to how hard he worked to learn that language, and I am in awe.

-

Reading another work by Takasu was very interesting because it gave a different perspective about his life. His essay on his impression of foreigners demonstrated a larger amount of opinion compared to other essays and other Japanese writings, so having a background information about his life shares a new viewpoint. Takasu’s autobiography, comparable to his other essay, gives insight to differences between western countries and Japan once again. For example, he describes how Japanese nurses care for infants and take on the role of a mother, providing the means of education and milk. Other descriptions including how he spent his time reading books was also interesting. It is intriguing to see what books and authors were of interest at that time and how he viewed different genres. The way he describes books and the effects that they can have in reading is fascinating to consider. It seems to hint at his future in books and further education. As an autobiography, the insights that he provides about his own life seems more open compared to other works and perhaps that is because of the purpose of the assignment. He may only be giving brief comments such as “it was a fearful sight” or “it was very dull to learn”, but it seems Takasu was able to insert his opinion and general feelings about certain situations and how it may have affected him. This is very aligned with his style of writing and narrative in his first impression of foreigners essay. His description of the attack on the castle and the comparison of the destruction to a tree was a very interesting perspective giving more detail about the situation than would be expected. As he moved on describing his time of studies it was amusing that he found learning English to be boring and would rather spend his time playing. He also gives a historical perspective saying learning English was seen as dangerous as it could lead to Christianity. Following other accounts, western ideas and the English language are described as from “savages” and continuously Christianity is seen as a danger. He concludes by including more of his personal account and opinion by describing an encounter with a doctor for his vision, another interesting situation to envision as he describes it.