Being born into a Haitian American family is a treasure that I did not always value. I knew my father came from a different country and spoke a different language, but I never considered the distinction between our two cultures. My earliest memories of my dad involve him speaking Creole on the phone and eating foods I would never try. I was always accustomed to those differences, which is why I never bothered to learn about them. When I was a toddler, he insisted on teaching me Creole but gave up because he said I was not exposed to it enough. When he was not around, I was only spoken to in English because none of my other family members spoke Creole. So, I ended up never learning the language.

My dad loved to make Haitian foods, but I never even tried one of them. Once I grew a little older, he would always tease me about being cultureless when I was raised by someone who was full of culture. Admittedly, he always tried to tell me stories about his life in Haiti, but when I was young, they always sounded like those “back in my day” rants that older people go on. I never really paid much attention to his stories about Haiti because it felt too impersonal. I had never gone there or met any of my family from there, so it was hard for me to be interested.

My dad died when I was fourteen. Since then I regretted choosing not to learn more from him. We always had a close relationship, so I knew he was not upset about it, but I afterwards felt horrible for being unaware of an entire portion of his identity.

After he died, I felt too guilty to learn about Haiti and Haitian culture from anyone else. It felt like I was betraying him. Ironically, after he died, I was surrounded by Haitians at school and work, and they made fun of my lack of culture. Once, at my first job as a patient sitter, I met Eugene Agboste. He always teased, “Your Haitian blood is so thin that you could lose it if you nipped yourself shaving.” As a result, he taught me so much about Haitian culture. He taught me about Haitian politics, agriculture, struggles, and successes. He is the reason I no longer feel like a disappointment to my father and our roots. I kept in contact with him because he grew to be like an uncle to me, and all that he taught me helped me to feel more connected to my dad, even though he is not physically here anymore.

I chose to interview Mr. Eugene Agboste because I hope his experience and wisdom can educate others who know nothing of the culture.

Background

Eugene Agboste is from Port-Au-Prince, the capital of Haiti. He moved from Haiti to East Orange, New Jersey, in 1988 when he was four years old. Accompanying him were his mother and grandmother. His father chose to remain in Haiti with Eugene’s older brothers, who felt that they were too far into the Haitian education system to transfer to schools in America. Sadly, Eugene’s father died in the catastrophic 2010-earthquake, and that was also the most recent time he traveled back to Haiti. Eugene got his degree in Health Sciences from Fairleigh Dickinson University, where he graduated Summa Cum Laude. He and I met at St. Michael’s hospital, where I worked as a patient sitter after school. He was the Patient Access Manager in charge of ensuring the proper care of the patients and that we were adequately fulfilling our duties. He was one of the only male administrators in this field. Still, we always spotlighted his tireless contributions, admirable work ethic, and everlasting impacts he made in the lives of patients and employees. Fortunately, I had the pleasure of being one of the employees graced by his influence.

The Interview

Me: Why did your family choose to leave Haiti and come to America?

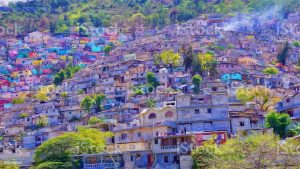

Eugene: For no other reason than further opportunity. Haiti is very limited in educational and occupational opportunities because there were not many other career fields outside of politics and agriculture that allowed people a chance for growth and incremental success. My family was very poor for generations. By the time I was two years old, my mother and grandmother formalized a plan that would allow us to migrate to America in a year, and they stuck to that plan. They wanted me to go to college and be better educated than they were.

Me: When you visit Haiti does it make you feel closer to your Haitian roots?

Eugene: Sure. Returning to Haiti isn’t something I get to do frequently. So, when I went back after I lost my dad, I cried like a baby. The air alone made me feel reunited and reconnected with that part of my identity. Going back to Haiti always reminds me of all we take advantage of in America. When I went there for my dad’s funeral, my aunts and cousins cooked food I hadn’t had in years. They get the pork shoulder for their griot straight from the market. Over there, we don’t really have fridges, so some of the marketers have live animals you can choose from, and they slaughter, clean, and package the meat right in front of you. Then for the Haitian patty, they make the dough from scratch. Everything is so homemade and authentic compared to how we have to prepare it in America.

Also, with showering–man it’s so much different. We get the water from a stream, maybe two miles away from the house, and that water is used for cooking, bathing, brushing our teeth, washing our hair, pretty much everything. So everyone only gets one very cold cup of water to shower and you have to make that one cup enough to clean your entire body–every crack and every crevice. The experience makes a great story to tell, but living in that and enduring those conditions is so much different compared to life here.

Me: What are some parts of Haitian culture or Haitian traditions that you felt your children needed to know about?

Eugene: The music. Kompa, speaks to the true nature of our culture. If you listen to the songs, you’ll see that they speak a lot about liberation and pride. So, I always say I failed my kids by not teaching them Creole, but even though they don’t speak it, they know how to sing the songs like they’ve spoken Creole since birth. I don’t think I’d like them as much if they didn’t enjoy Kompa. (The last sentence was a joke.)

Here’s a link to some Kompa music! Give it a listen!

Me: What makes you proud to be Haitian?

Eugene: The History. The fact that we have a country to call our own. Even though it’s a third-world country and one of the peninsula’s poorest, it’s still home.

Also, Haitians were the first to revolt successfully. Looking at the state of our nation and how at times, we’ve struggled to thrive, people pity us, but we are a proud people.

Me: Would you recommend non-Native Haitians to experience the country? Why or why not?

Eugene: Sure. I would recommend them to experience it personally, but honestly, I wouldn’t consider it dire to their identity. There is plenty of the culture and of the culture that they can learn from their families and friends. Haiti is in a state right now that probably isn’t the best condition for tourists, but once things get better, I’d hope everyone would try to see it.

Conclusion:

Eugene’s answers helped me to have a better understanding of Haitian culture and the authenticity of Haiti. I would love to travel there and experience their way of living for myself. Until then, I will continue to learn more about my culture and identity.