Collected sediment is described in detail on the ship, as soon as possible after core sections are split. It is important to record these observations quickly, as shrinkage and color change can occur as water evaporates from the sediment.

Believe it or not, many words can be used to describe mud. I was able to obtain a small discarded sample of mud from a core, and I conducted a brief survey of the ship as to its appearance:

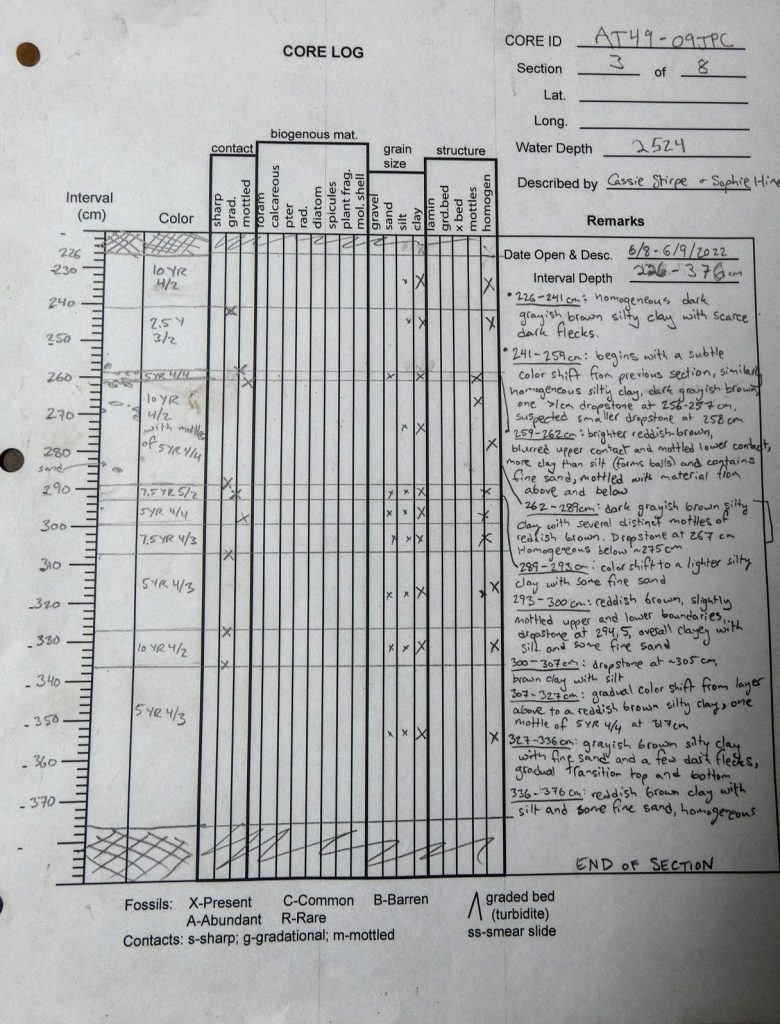

Core Log

The scientific describing of mud is much more formalized. For each core section, a detailed “core log” is completed. On the log, the following items are noted, all based on depth: 1) rough sketch of core; 2) color; 3) contacts between sediment types; 4) nature of contacts (sharp, gradational, mottled); 5) contained biogenous matter (foraminifera, plant fragments, shell fragments); 6) nature of sediment (for example, calcareous sediment is very chalky); 7) grain size (gravel, sand, silt, clay); and 8) structure (laminated, graded bed, mottled, homogenous, etc.). There is also a large space for extra observational remarks.

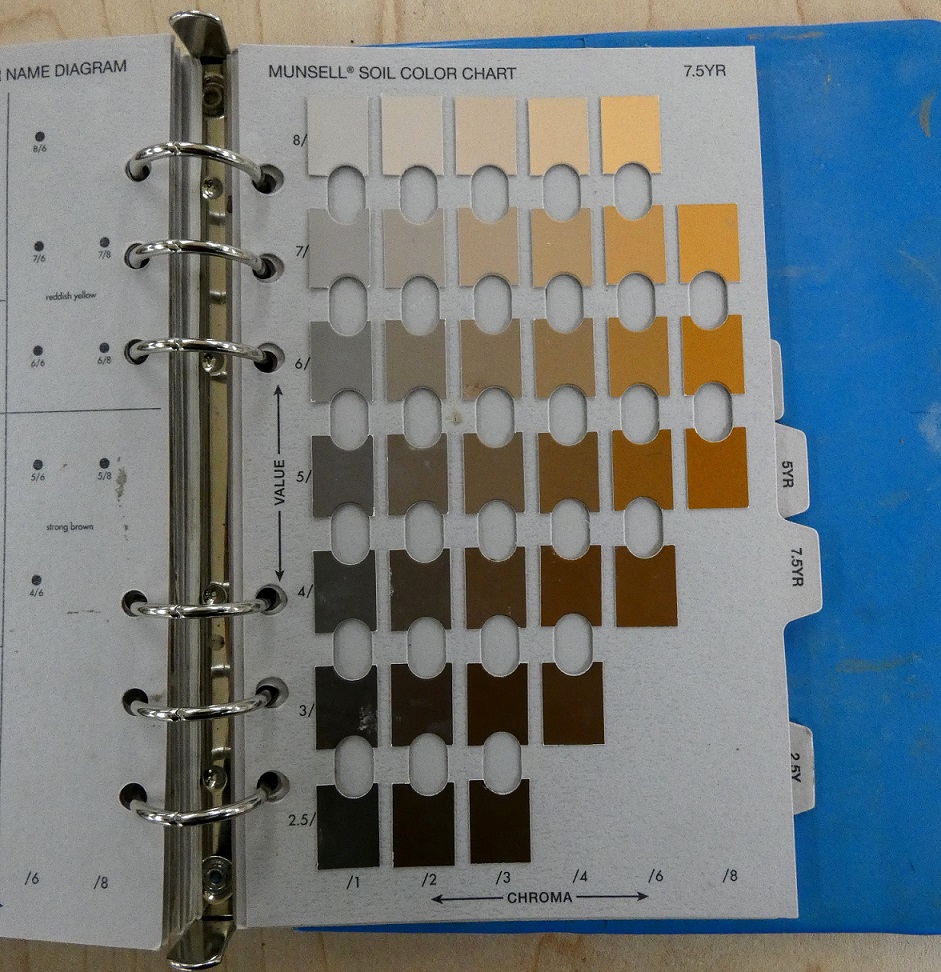

50 Shades of Brown

The mud we have collected has mostly been brown to gray. Sometimes, we have seen reddish beds and/or streaking within the mud, due to the oxidation of metallic content. Once, the mud from a series of multicore tubes was uniformly green. To assign mud layers a specific color, a soil color chart is used (1) that is colloquially referred to as “50 Shades of Brown”.

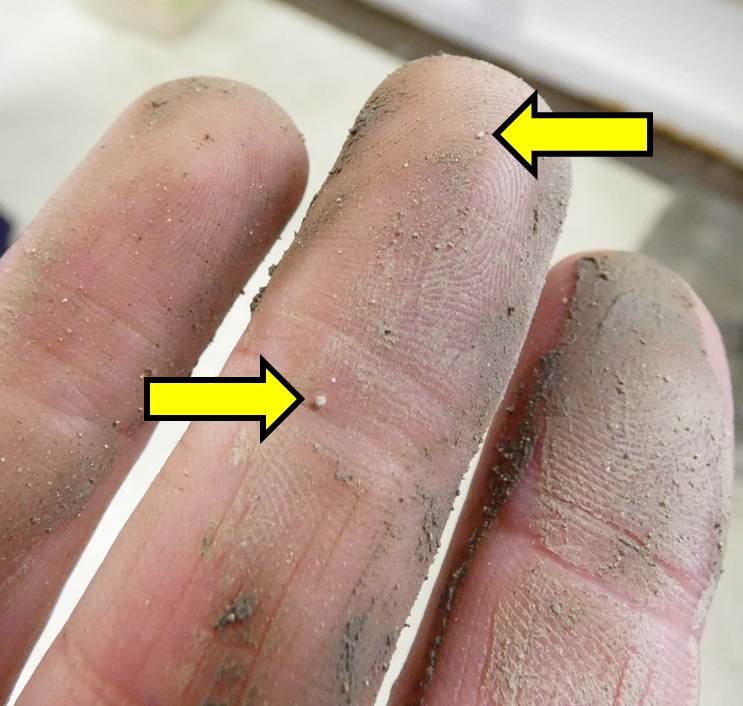

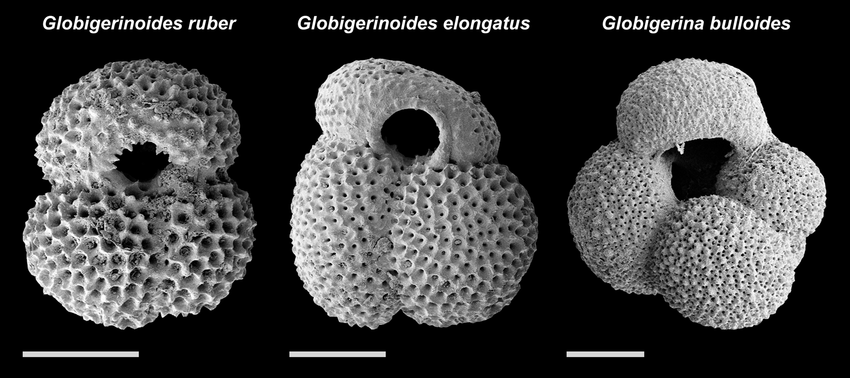

Consistency

The texture of the mud has varied quite a bit. Some has been gritty and crumbly, some has been moist and sticky. The muddy sediment recovered off the coast of Nova Scotia was quite gritty, due in part to the presence of foraminifera. These are tiny (usually less than 1 mm) fossils of amoeboid protists that live in the ocean, either on the ocean floor (benthic) or as plankton (planktonic). These fossils are of immense importance to paleontologists, paleoclimatologists, and paleooceanographers. Other fossils we have seen within the mud have included bivalves, gastropods, and tusk shells.

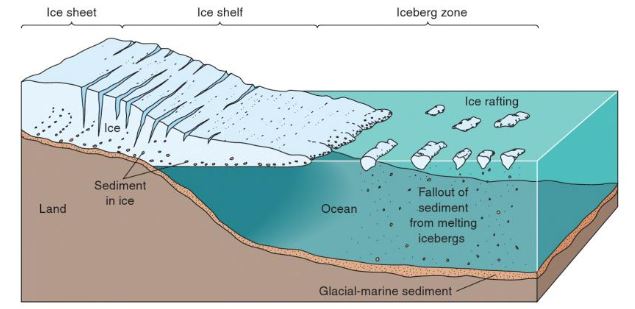

Mud has also commonly contained ice rafted debris. When ice melts after a certain period of drifting atop the sea, any solid material contained within the ice is released and eventually deposited on the seafloor (3).

Did You Know?

Anthropogenic material is also quite often found in seafloor sediment, especially that from the upper layers (collected via multicore). We’ve been separately sampling some of these sections to be later analyzed for microplastics. Mysterious black balls showed up frequently in one of yesterday’s core samples. Our best guess is that these were once droplets of crude oil, probably from an oil tanker. When crude oil droplets fall into the ocean, the more volatile components (smaller chained hydrocarbons) evaporate quickly, leaving behind balls of material of higher molecular weight. These “tar balls”, consisting mostly of saturated hydrocarbons, are quite inert and accordingly preserved in the sediment.

Wildlife Sightings

- Herring Gull

- Northern Fulmar

- Great Shearwater

- Sooty Shearwater

- Barn Swallow

Sources

- Munsell Soil Color Charts. Baltimore, Maryland, 1990.

- Weinkauf, Manuel F. G., et al. “Seasonal Variation in Shell Calcification of Planktonic Foraminifera in the NE Atlantic Reveals Species-Specific Response to Temperature, Productivity, and Optimum Growth Conditions.” PLOS ONE, vol. 11, no. 2, 9 Feb. 2016, p. e0148363, 10.1371/journal.pone.0148363.

- Bischof, Jens. Ice Drift, Ocean Circulation and Climate Change. London, Springer, 2001.

- Pinet, Paul R. Invitation to Oceanography. Burlington, MA, Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2021.