N. Iriye

Sketch of My Life

(Transcribed by Rachelle Cha and Shrusti Goswami)

I was born in Uwajima, a town situated in the province of Iyo, on the southern part of the Shikoku Island. Uwajima is a small castled town situated on a harbor, and is enclosed by steep high mountains on one side and by green hillocks on the other. In the midst of the town, rises a small hill on which the castle is built. That hill is covered with pine and other ever-green trees, and between the green leaves, the while walls of the castle appears here and there, and on the top stands a three-storied Tensu. Though the city is not very large, the climate is exceedingly mild, and the scenery picturesque, so that it is a very pleasant place to live. Mr. Sato, an English interpreter, when he came to my province said that the harbor resembles that of Nagasaki. About the time of my birth, the symptoms of the fall of the Feudal System first appeared and the power of Tokugawa Shogoon began to decline. Treaties were nearly made with foreign countries, and there were many persons who hated strangers; but contrary to the advice of Karos, Prince Date adopted foreign style of drill, and also sent scholars to Nagasaki to learn Dutch and English languages. When the princes of neighboring provinces began to introduce foreign style of drill, soldiers of my province were so advanced that many of them were employed as teachers.

According to the custom of Japan, I spent the early part of my life without studying anything – a loss which is irreparable in my whole life. When I was about six years old, I began to attend primary school in which writings of Japanese and Chinese characters and the reading of Japanese history and Chinese classics were taught, and examinations were held at the end of each month. It was a public school and all Samurais and afterward even Ashigaru were allowed to enter without paying any fee. At that time, it contained about three hundred scholars. At the end of each year, prizes were given from the Prince to diligent scholars, which consisted of Japanese pens, papers, fans or books. There was a large school called Meirin Kwan in which Chinese classics, history, poetry, tactics, English and Dutch languages, and many military arts such as fencing, the use of spear, bow, musket too were taught. Besides these, there were schools for riding, and for swimming. The latter was considered one of the best accomplishments of Samurai class in many provinces which are situated on seashores. Those who could not swim, were exceedingly disgraced, at least in my province, and were called by several nicknames, such as “stone Buddhist idol” (Ishi Botoke), “stone mill” (Ishi Usu), or gun-ball (Teppo Dama). The exercises of bow and spear were abolished, when the Prince first introduced the foreign drill.

Tactics were taught by a celebrated general in the Revolutionary war, named Omura who had fled from Choshiu and were received by the prince. He commanded the imperial army in the battle of Uyeno. When he was informed that the imperial army was victorious, he is said to have made a poetry which briefly means that both the conqueror and the conquered must feel compassion toward the other, if they reflect that both are the same fellow-countrymen. He also commanded the imperial army in the north. Soon after the war was ended, he was assassinated in Kioto, and was much regretted by the people.

While I am writing my own life, I must not enter too deeply into the history of other person. When I was seven years old, I began to go to the swimming school, and when I was about ten years old the prince of Choshiu became Choteki or Imperial enemy, and the Shogoon Tokugawa came to Osaka in order to punish him with war. All the princes who governed the provinces near Chioshiu were ordered to send forces to assist those of the Shogoon. But, at that time the power of Tokugawa began to decline, and many of Daimios were not willing to obey his command. As the wife of the prince Uwajima was the daughter of the prince Choshiu, and his father had been unjustly compelled by Ji, who was the chief officer of Tokugawa, to resign his office and live in retirement though he was not very old, Samurais in my province had no motive to take up arms against Choshiu. But the prince led them to the opposite coast. The scene of the military procession was very curious.Though soldiers who were chiefly Ashigaru class, were well-trained and had guns, some obstinate Samurais carried swords and spears and even wore armours. Commanders carried batons or fans called Gunbai which is made of wood or iron and is used in giving command. Ships in which they were to cross the sea were small and ill-built and it was evident that they would have been defeated, had they dared to invade.

When I was eleven years old, I began to learn fencing and Taijutsu which is a kind of wrestling in which how to throw another and take prisoners was taught. Although the exercises of bow and spear had already been abolished, fencing was still flourishing and each province in Shikoku used to send fencers to other provinces to try their skill. At the time of the last revolution, I was about twelve years. At that time, the prince of Matsuyama, governor of the neigboring province attached to Tokugawa, and the princes Tosa, Choshiu and Uwajima were ordered to send forces to the city of Matsuyama. As the soldiers of Choshiu had found armour very inconvenient, when they had fought with the army of the Shogoon, they wore no armour in the Matsuyama expedition.

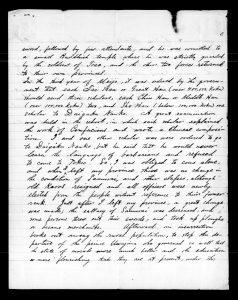

As my father were sent thither as a commander of artillery, he took me with him to Matsuyama. When the forces of the three provinces surrounded the castle in which the prince Matsuyama lived, he saw that he could not resist and surrendered at discretion. He came out of the castle without sword, followed by four attendants, and he was comitted to a small Buddhist temple where he was strictly guarded by the soldiers of Tosa, and the other two forces returned to their own provinces.

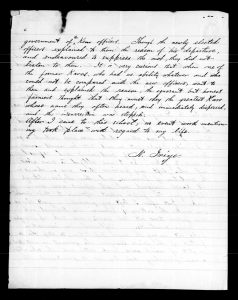

In the third year of Meiji, it was ordered by the government that each Tai Han or Great Han (over 400,000 Koku) should send three scholars, each Chiu Han or Middle Han (over 100,00 Koku) two, and Sho Han (below 100,000 Koku) one scholar to Daigaku Nanko. A great examination was held in the school, in which each scholar explained the work of Confucious and wrote a Chinese composition. I and one other scholar were ordered to go to Daigaku Nanko, but he said that he would never learn the language of barbarians and refused to come to Tokio. So, I was obliged to come alone, and when I left my province, there was no change in the condition of Samurai, and other classes, although old Karos resigned and all officers were newly elected from the people without reference to their former rank. Just after I left my province, a great change was made; the sallary of Samurai was decreased, and some persons threw out their swords, and took up ploughs or became merchants. Afterward, an insurrection broke out among the rural population, to stop the departure of the prince Uwajima who governed so well that the state of morals were much better and the education more flourishing than they are at present, under the government of the Ken officers. Though the newly elected officers explained to them the reason of his departure, and endeavoured to suppress the mob, they did not listen to them. It is very curious that when one of the former Karos, who had no ability whatever and who could not be compared with the new officers, went to them and explained the reason, the ignorant but honest farmers thought that they must obey the greatest Karo whose name they often heard, and immediately dispersed and the insurrection was stopped.

After I came to this school, no event worth mentioning took place with regard to my life.

N. Iriye

-

-

This essay by N. Iriye on his life was very surface level and more informative than personal. From this essay, we learn the basics of Iriye’s life, such as where he was born and where he went to school. Something interesting I’ve come across is how much Iriye loves education. He describes not going to school in his early life as a “loss which is irreparable in my whole life.” Iriye describes his schooling with great care. He talks about his primary education and what he learned then and about going to a swimming school. He was one of two students chosen to go to Daigaku Nanko.

Weaved into this story about his schooling was his account of the fall of the Tokugawa and the beginning of the Meiji Restoration as well as remarks about his town. Through Iriye’s description of the Prince of Uwajima, he is a progressive man. Members of the Uwajima army were exposed to the foreigner’s style of drill long before other neighboring provinces. The Prince also sent scholars to learn Dutch and English. After Iriye left for Daigaku Nanko was when real change was starting. He talks about how the town rebelled when the Prince stepped down, and the newly elected officials came to power. He also described that “old” Uwajima had a better education system and better morals than the “new” Uwajima.

In the early stages of the Meiji Restoration, Iriye probably believed that the Feudal System was fine because his town was so ahead of the times that this shift felt like Uwajima was regressing. However, in his autobiography, he describes the farmers as ignorant, which shows that now, he believes in the Meiji Restoration and believes in this new system.

Based on this autobiography and the essay on foreigners, I have gathered that Japanese people don’t frequently share personal opinions. They like to stick to the facts and mainly describe events rather than express how they felt about those events.

-

I found N. Iriye’s autobiography very interesting. Based on what he wrote, His passions lie in education, history, and government. Iriye begins his autobiography with his life as a child in Uwajima, describing it as “small castled town situated on a harbor, and is enclosed by steep high mountains on one side and by green hillocks on the other” and tells the reader about the green leaves and hills, the “mild climate,” and that it is a “pleasant place to live.” He says such opinions as facts, which leads me to believe he thought very fondly of his province, which he would later leave for education at Daigaku Nanko. Early on, it’s clear he values education by his regret of not attending school until he was six years old, which he describes as “a loss which is irreparable in my whole life.” But afterward, Iriye goes into detail about school events such as the annual ceremony where hardworking students could win prizes. Although this is his autobiography, Iriye doesn’t mention his actions much like, for example, if he ever won a prize. We later find out that Iriye was one of two scholars sent to Daigaku Nanko, a prestigious school, but don’t hear much about his feelings towards leaving his province and attending a new school.

He is also interested in history. Iriye explains that when he was born “the symptoms of the fall of the Feudal System first appeared and the power of Tokugawa Shogun began to decline.” Perhaps this explains his later interest in law and changes in the new government. He mentions in his autobiography how soldiers acted and dressed and stated,” though soldiers who were chiefly Ashigaru class, were well-trained and had guns, some obstinate Samurai carried swords and spears and even wore armours.” I found this interesting as he wasn’t a soldier himself. He does mention that his father was sent to Matsuyama and he traveled with him, so it seems as though military life was somewhat personally relevant to him.

Lastly, I see how Iriye shared his opinions of the new government. He gives a strange example of how trouble arose in the rural areas when the Prince Uwajima “who governed so well that the state of morals were much better and the education more flourishing than they are at present” was leaving and new officials were taking his place. Iriye tells the reader that the farmers didn’t listen to the new officials who provided an explanation for the prince’s departure but listened to an old Karos, even though his position was insignificant. This whole incident happened in Iriye’s old province while he was already away at school, so I find it telling of his connection to his province that he would include such in his autobiography. He is aware of the changes in his province and maybe even the changes in his own opinion. Although he praises the morals taught under Prince Uwajima’s rule, he calls the farmers “ignorant” for listening to an old Karos member. This indicates a discrepancy in Iriye’s opinions, perhaps because he is now an outsider looking into the politics of his province.

Overall, I can see where some of Iriye’s interests lie, particularly in education, history, and government. But there is a lack of personality in this piece and as a reader, we learn little about Iriye’s opinions or personal experiences. Rather, we read opinions stated as facts and must dig deeper to find Iriye’s true beliefs about the events in his time.