N. Kishiro

My First Impression of Foreigners

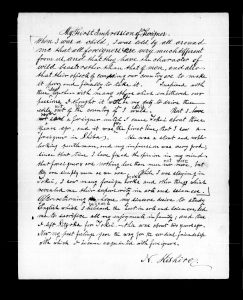

My First Impression of Foreigners

(Transcribed by Evan Feldman and Emily Sun)

When I was a child, I was told by all around me that all foreigners are very much different from us, and that they have the character of wild beasts rather than that of men, and also that their object of coming our country are to make it poor and finally to take it. Inspired with these ideas together with many others that embittered our passions, I thought it would be my duty to drive these evils out of the country if I could. But I never saw a foreigner until I came Tokei about three years ago, and it was for the first time that I saw a foreigner in Shiba. He was a stout and noble-looking gentleman, and my impression was very good; since that time I have fixed the opinion in my mind that foreigners are nothing less than men not more, but they are simply men as we are. While I was staying in Tokei, I saw many foreign books and other things which revealed me their superiority in arts and sciences. After returning home my sincere desire to study English which I believed the best in arts and sciences, led me to sacrifice all my enjoyments in family; and thus I left Sitzoka for Tokei.–This was about two years ago. Now my past feelings gave the way for the cordial friendship with which I became acquainted with foreigners.

N. Kishiro

-

-

This essay depicts the stark contrast between how the Japanese viewed foreigners before they first met them in comparison to how they viewed them after they had interacted with them. Before he had seen foreigners, Kishiro had believed that they were all the same and desired to exploit the wealth of the Japanese. His concept of foreigners was that they were “very much different from us” and compared them to “wild beasts.” This description reflects how Japanese society perceived foreigners before they ever interacted with them. This exaggerated characterization also spread due to the fact that many Japanese had never seen people from other countries before the Japanese borders were opened. In a propagandistic fashion, the Japanese who held positions of power were capable of instilling the idea in their people that Westerners were backwards people. In other words, the Japanese viewed Western culture and values as inferior to theirs: they believed Japanese morals and ethics were superior to Western practicality and materialism.

Once the foreigners and Japanese started interacting with each other, the belief that foreigners were like “wild beasts” began to fade. As stated in his essay, Kishiro realized that foreigners “are simply men as we are” and as more of the Japanese met foreigners, they learned they shared many similarities. Kishiro’s essay indicates that once the mysteriousness of the West was lifted as a result of the opening of Japan’s borders, myths about the West soon began to dissipate as well. This is because both Westerners and the Japanese realize that despite their differences in culture, language, and appearance, people are people. Kishiro even expresses sentiments of friendship with the Westerners once his preconceived notions were dispelled. After studying advanced Western arts and sciences in Tokyo, Kishiro recognized the value of Western technology and the importance of developing relationships with Westerners. His decision to learn English and leave his family for Tokyo showcase how his education Westernized him. Nonetheless, despite some of the loss in Japanese culture and values, essays like these illustrate some of the benefits of opening Japanese borders and how doing so reduces Japanese prejudice towards foreigners.