Women and Missionaries

By Rachelle Cha (’23), Caitlin Moy (’23), and Aishwarya Sridhar (’21)

As Japan began to look towards Western ideals for reform, developing its education system and adapting to the arts and sciences of the West, missionaries proved to be a necessary component in this process. With Guido Verbeck teaching English in Nagasaki and advising the Meiji Government in foreign affairs, John Ferris welcoming the first Japanese students to America, and James Hepburn helping to modernize Japanese education by founding what would become Meiji Gakuin University, missionaries such as these acted as a bridge between cultures.

While male Westerners, such as Verbeck and Hepburn, who were missionaries and Ferris, who was the secretary of the Board of Foreign Missions, helped modernize Japan as a whole, many women played a significant role in the modernization of Japanese education for girls. Due to the efforts of women such as Margaret Griffis and Mary Kidder, schools for Japanese girls thrived. They gave Japanese young girls a well-rounded education, including knowledge about the English language. Some of these girls would go on to study in Western nations and help bridge the gap between the Japanese and Western cultures.

Photograph of prominent missionaries Verbeck, Brown, and Simmons who all served in Japan in 1859, appearing in Griffis’s biography of Verbeck, Verbeck of Japan: A Citizen of No Country. These missionaries had a lasting impact on the development of Japanese foreign affairs and foreign education.

Despite a ban on Christianity that was not lifted until 1873, missionaries like Guido Verbeck played a key role in Japan’s modernization. As discussed in William Griffis’s 1900 biography, Verbeck of Japan: A Citizen of No Country, government officials frequently turned to Verbeck for advice in foreign relations, and to translate constitutions and legal documents from English, German, and French into Japanese (Laman 88). In a copy of a letter sent by Verbeck to John Ferris in 1872, he discusses his ideas for sending an embassy to the west, and other propositions for the Meiji Restoration Government- ideas that would be implemented by the Japanese government, all while omitting his suggestions of Christianity (Altman 54-62). A resource to the government in foreign education and affairs, Verbeck also played a role in bringing Griffis to Japan to teach in Fukui.

Portrait of John Ferris, a member of the Dutch Reformed Church who played a key role in connecting missionaries in Japan with the Dutch Reformed Church in America.

From his office in New York, John Ferris, the secretary of the Board of Missions for the Dutch Reformed Church, served as a point of contact for the missionaries in Japan. As a frequent correspondent of Guido Verbeck, Ferris was essential to the process of bringing young samurai from Japan to study at Rutgers College and Rutgers Grammar School. In Dr. David Murray: Superintendent of Education in the Empire of Japan, 1873-1879, the encounter in 1866 between John Ferris and the Yokoi Brothers, the first Japanese students at Rutgers, is described:

“They presented a letter from Rev. Guido Verbeck, then in Nagasaki, in which it was said only that they had been a few months in Dr. Verbeck’s school, had learned some English there, and picked up more on the long voyage of about six months. They wished, they said, to study navigation, to learn how to build “big ships” and make “big guns” to prevent European powers from taking possession of their country.”

Ferris proceeded to take the brothers to New Brunswick and make arrangements for them to enroll at Rutgers Grammar School. This encounter set in place the process of sending samurai to Ferris’s office with letters from Verbeck promoting the start of their education in New Brunswick (Duke).

James Curtis Hepburn

James Curtis Hepburn and his wife Clara Hepburn

James Curtis Hepburn and his wife Clara founded the Hepburn Academy, also known as the Hepburn Juku, in 1863, in Yokohama, Japan. This school integrated Western education ideals and helped modernized Japanese education. This school would eventually become Meiji Gakuin University, a now well-known Christian University in Tokyo, Japan. Hepburn arrived in Japan as a medical missionary while advocating for Christianity. His wife, Clara, assisted William Elliot Griffis’s sister, Margret Clark Griffis, in the newly established Jo-Gakko school for girls in Tokyo. Griffis’s book “Hepburn of Japan” contains an address from the Japanese churches to Hepburn contained praises for Hepburn stating:

“‘It is now thirty-three years ago — when Japan was but one of the darkest spots on the globe — that you landed on our then unwelcome shores.’ The Doctor was congratulated as a pioneer and as a physician — the ‘father of medical science in this part of Asia’” (Griffis 188)

His greatest accomplishments in Japan include writing the first Japanese-English dictionary, translating the Bible into Japanese, and providing medical care to the Japanese people. His system of Japanese-English Romanization is still used today, known now as the Hepburn System.

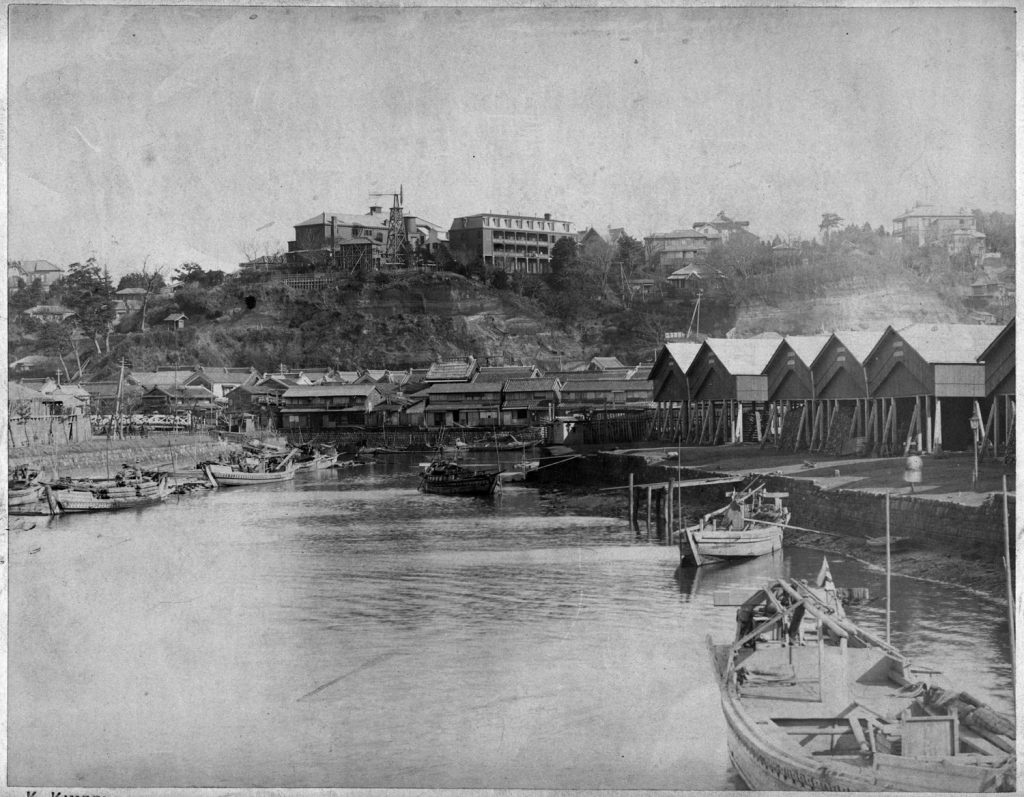

Meiji Gakuin University in 1927

Meiji Gakuin University was formed by the merger of three schools: the Tokyo Union Theological School which was founded in 1877 by the Missions of the Presbyterian Church, the Reformed Church of America, and the United Presbyterian Church of Scotland; the United Japanese-English Union College, founded in June 1883 by the Missions of the American Presbyterian and the Reformed Churches, and the Japanese English Preparatory School. These last two schools were successors of the Hepburn Academy. James Curtis Hepburn would go on to become the first President of Meiji Gakuin University.

After serving as principal of Isaac Ferris Seminary for 6 years, Kidder retires and passes on the role of principal to Eugene S. Booth. As Kidder continued her evangelism work with her husband, the Isaac Ferris Seminary continued to grow. After being a girl’s school for many years, in 1965, Ferris Seminary expanded and became the Ferris Women’s College. Today, Ferris College is a Christian institution that consists of a college, high school, and junior high school.

Isaac Ferris Seminary

Mary Eddy Kidder, coming from the United States in 1870, was the first female missionary to Japan. After hearing Reverend Brown’s speeches about how educating women will bring forth the modernization of Japan, Kidder felt a strong conviction to go to Japan to teach girls. She began teaching in one of the rooms in Dr. James Hepburn’s infirmary. Her students were pupils of Hepburn’s wife, some of whom were girls. As the number of girls wanting to learn increased, Kidder received approval from the vice-governor of the Kanagawa prefecture, Ooe Taku, to move her class to the prefectural residence. On Jun 1, 1875, Kidder’s school was built and was named Isaac Ferris Seminary in honor of Isaac Ferris, the secretary of the Board of Foreign Missions for the Reformed Church in America.

Margaret Griffis

Margaret Clark Griffis and Her Students

Margaret Clark Griffis joined her brother, William Elliot Griffis, in Tokyo, Japan, in 1872. She is credited with helping modernize Japanese women’s education. Margaret Griffis lived in Philadelphia with her two sisters prior to her experiences in Japan. From 1872 to 1874, she served as a teacher and assistant principal in the Jo-Gakko girls school, the first Japanese government school for girls, which later became the Tokyo Female Normal School. Margaret Griffis’s diary from 1874 to 1905 contains personal details about her experiences teaching in Japan. About thirty-five student autobiographies by Margaret’s Japanese students at Jo-Gakko, written in English script, are present in the Griffis Collection at Rutgers University. Margaret Griffis returned to America with her brother in 1874 and continued to teach female students in a Philadelphia school for girls until 1898. She died in Ithaka, December 15th, 1913.

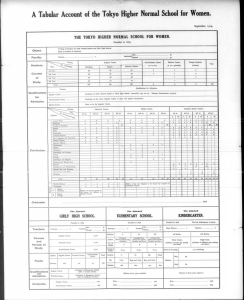

This is a Tabular Account of the Tokyo Higher Normal School for Women, at which Margaret Griffis served as a teacher and assistant principal. The image shows that the school had an enrollment of 445 girls and offered classes including drawing, ethics, history, physics, and many more. The students at the school not only learned English and Japanese, but also had a very well-rounded education.

Tsuda Umeko

Tsuda Umeko founded Joshi Eigaku Juku in 1900 which was one of the first private schools for women’s higher education. In its early days, the curriculum was largely influenced by Bryn Mawr, a women’s liberal arts college and Tsuda’s alma mater. Students studied English three hours each week and were also offered electives to complement their required courses. Today, Joshi Eigaku Juku has grown tremendously and is now called Tsuda University. Tsuda University keeps true to its roots by focusing the curriculum on a liberal arts education and putting a special emphasis on language learning.

After spending much of her youth in America, Tsuda experienced a huge culture shock when returning to Japan. She was dismayed by the prejudice experienced by women in Japan and decided that this could be remedied through women’s higher education. This leads to the creation of her scholarship program and Tsuda University.

Tsuda Umeko, formerly known as Tsuda Ume, was one of the five girls sent to America with the Iwakura Mission. Only seven years old at the time, Tsuda stayed in America to fulfill her mission of becoming the future of women’s education in Japan. After studying in America for a decade, Tsuda came back to Japan to set up a scholarship system for Japanese women in 1891 and taught at a women’s school briefly. She then went back to America to study at Bryn Mawr College. Tsuda founded Tsuda University, originally called English School for Women (Joshi Eigaku Juku), in 1900.

-

Altman, Albert. Guido Verbeck and the Iwakura Embassy. Vol. 1, Japan Quarterly 13, 1966.

“General Statement.” Calender of the Meiji Gakuin, Suieisha, Tokyo, 1890.

Duke, Benjamin. Dr. David Murray Superintendent of Education in the Empire of Japan, 1873-1879. Rutgers University Press, 2019.

Ferris University. フェリス女学院の教育|学校法人フェリス女学院, www.ferris.jp/education/index.html.

Ferris University. “History of Ferris.” History of Ferris, www.ferris.ac.jp/en/about-ferris/History_of_Ferris.html.

Griffis, William Elliot. Hepburn of Japan. The Westminster Press, 1913.

Griffis, William E. Verbeck of Japan: A Citizen of No Country. Fleming H. Revell Company, 1900.

Hommes, James Mitchell. “Verbeck of Japan: Guido F. Verbeck as Pioneer Missionary, Oyatoi Gaikokujin, and ‘Foreign Hero.’” University of Pittsburgh, 2014.

“J.C. Hepburn.” Meiji Gakuin Historical Museum, Meiji Gakuin University, shiryokan.meijigakuin.jp/archive/people/hepburn.

Jo Gakko autobiographies and educational materials. 1859-1928. Government Papers. The National Archives, Kew. Research Source. Web. May 07, 2020. <http://www.researchsource.amdigital.co.uk.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/Documents/Details/JTWE_Part4_Reel60_Vol1>.

Laman, Gordan M. Pioneers to Partners: The Reformed Church in American and Christian Mission with the Japanese. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2013.

Margaret Clark Griffis papers: Journals and diaries, 1874-1906. 1874-1906. Government Papers. The National Archives, Kew. Research Source. Web. May 07, 2020. <http://www.researchsource.amdigital.co.uk.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/Documents/Details/JTWE_Part4_Reel59_Vol1>.

“Meiji Gakuin University: Institution Main.” Institution Main – Meiji Gakuin University, North American Coordinating Council on Japanese Library Resources, guides.nccjapan.org/meijigakuin.

Printed materials: Pamphlets and periodicals collected by W. E. Griffis, vol. 4. 1911-1926. Government Papers. The National Archives, Kew. Research Source. Web. May 06, 2020. <http://www.researchsource.amdigital.co.uk.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/Documents/Details/JTWE_Part4_Reel64_Vol1>.

Tsuda College. “Profile.” Tsuda University, www.tsuda.ac.jp/en/profile.html.

Terzuolo, Chiara. “Daughters of Meiji: Bringing Women’s Education to Japan.” Public Relations Office, Government of Japan, www.gov-online.go.jp/eng/publicity/book/hlj/html/201810/201810_06_en.html.

“University History.” About Meiji Gakuin University, Meiji Gakuin University, www.meijigakuin.ac.jp/en/about/history/guide/history8.html.

Yoshiro, Tabei. “The Journey of Mary Eddy Kidder, Pioneer in Women’s Education in Modern Japan – The United Church of Christ in Japan.” The United Church of Christ in Japan, The United Church of Christ in Japan, 5 Oct. 2009, uccj-e.org/knl/1189.html.

-

“Meiji Gakuin University: Institution Main.” Institution Main – Meiji Gakuin University, North American Coordinating Council on Japanese Library Resources, guides.nccjapan.org/meijigakuin.

“J.C. Hepburn.” Meiji Gakuin Historical Museum, Meiji Gakuin University, shiryokan.meijigakuin.jp/archive/people/hepburn.

Van Heest, Valerie (Ed.). (2009). A Century of Science: Excellence at Hope College. Holland, MI: Hope College.; page 16

“Verbeck, Brown, Simmons.” Archives of the Reformed Church of America, New Brunswick.

“Umeko Tsuda at Graduation 1890.” Wikipedia, 22 Nov. 2007, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Umeko_Tsuda_at_graduation_1890.jpg.