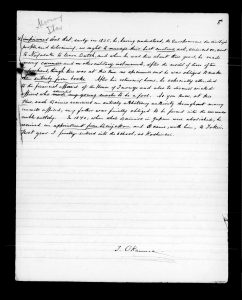

T. Okamura

The Sketch of My Life

(Transcribed by Raj Malhotra and Caitlin Moy)

Though the reign of Tokugawa is the one which continued peacefully for a long time, that is, for about two hundred years, yet, from the time when I was born (1855), it gradually begun to decline and many changes took place. As, at this period, the principle of Feudalism still existed in Japan, each Daimio employed his own arbitrary policy to govern his subjects, without reference to any other Daimio or his master. Consequently, the customs, manners, and many other things of the one’s subjects were quite different from those of others. What I shall hereafter describe, will therefore be the events which particularly took place in my native provinces, Setzu (in the city Osaka) and Totomi (in the city Hamamatsu)

The general feelings of the people—As the government of Tokugawa imposed unreasonable taxes and practiced many cruelties upon its people, their feelings toward the government were usually very bad. But, having been accustomed to be governed by such a government for a long time, they rather wished its continuance, than any change. Their impressions towards foreigners were, of course, very strong and barbarous, so that, they, even I, thought it would be our duty to fight against them, when we thought, they came in order to conquer Japan. But the following events, which our uncivilized people supposed to be the true auguries of their destruction, gave great energy to the above opinion and quickened to the ruin of the government of Tokugawa.

- Many great earthquakes and famines visited almost all parts of Japan and carried thousands of people.

- The price of every thing arose so high that the poor could not sustain his life and the middle class was reduced to abject poverty. We thought, the cause of this event was that foreigners carried away all productions of Japan.

- The appearing of a new comet, which the Chinese and the Japanese thought to be the worst augury caused a great excitement among religious class.

- The death of the Emperor happened lately. The citizen of Kioto believed that black cloud, having two large eyes, appeared at the very night of the death of the Emperor, in order to show the outbreak of the war.

Their feeling towards religion was very different from each other. The Shinto religion influenced, at this period, the higher classes, Kuge, Daimio and Samurai, though not very extensively. The law, established in Mito, by which all branches of Buddhism was abolished and images, bells and other instruments belonging to churches and temples were used to make cannon and schools, influenced once the people of this province and all Shintoish scholars. The Buddhism had a great influence among the lower classes. The people of Osaka, even at present, strongly adhered to the Monto-shiu, so that, when the temple, Mido, was burnt up, thousands of citizens assembled and reestablished it without a delay. On the contrary, in my last province, Kadzusa, there were the strong adherence to Hotzuke-shiu, called Hichiri-Hotzuke. The people, living within the boundaries of [seven visor?] Hichiri, never married those of other provinces, and they did everything entirely exclusive of others.

Ranks, and the customs–As besides Kuge and Daimios, the whole people of Japan were divided into four great classes, the Samurai, Peasants, Carpenters, and Merchants, their customs and manners were, of course, quite different. The name Samurai, I think, included formerly both Kuge and Daimio; but it recently, meant only the subjects of Daimio. The manners of Kuge were very different from all others, for they were regarded as sacred, without any communication with the lower classes. Their general names were Goshio-gata, which means the members in the high palace, and sometimes Kumono-Uyetzo-gata, that is the members on the cloud, both meaning that they were too high and can not be touched. They always spent their time in playing, especially in making poems, without any particular business. Consequently, their customs were feeble and womanly. For instance, all Kuge, even the men, formerly blackened their teeth, embellished their faces with white powder, Oshiroi, and did several other things which now our women do. Though the customs of Daimio were very similar to those of Kuge, yet they were far superior to Kuge, because they had, as their subjects, the gallant and brave feudal tenants, Samurai, whose conducts were the basis of the manners of the present Japanese. One of the principles, which greatly affected the customs and character of Samurai , was that, they should give rip, to their master, their lives, like stones. Hence boldness, activity and the like were great honor. They said always “the soul of Samurai is the sword.” Particularly in the latter part of the Tokugawa’s reign, the fencing, riding and other heroic arts became the chief duty of Samurai, while no one attended to read and write. They, even at home, habituated themselves to run fast, not to suffer from hunger or thirst, and to awake early at night. It is also one of the curious customs of Samurai, that they should never put in their drawn swords into scabbards, without killing others. They made such a great mistake, that they regarded mathematics to be only the duty of merchants, therefore mathematicians were mostly found in the lower class. The moral of the privileges of Samurai, subjects certain large Daimios, was that they were allowed to kill any man, without a question, if he made something wrong towards them, even by mistake. This act was called “Kirisute-gomen” or an allowance to kill.

The above description is the brief account of the general influence and customs, particularly in the higher classes. Now I shall continue to write about my life, as simple as possible.

I was born in the 20th of the 7th month of Mangen (1855) at Osaka. At this period, the city was in a great confusion, on account of many wonderful works of nature. In the 6th month of the same year, that is, one month before my birthday, a great earthquake visited first the city, carrying away many hundreds of citizens. In both the 11th and 12th months, terrible earthquakes, together with dangerous storms, again laid waste on the whole part of the city. My parents told me that at this time, my female-servant, carrying me on her back, was taking in some part of the city, several chios distant from my house; when the vibration begun, though she attempted to return home, she could not do so and at the critical moment, she was laying down on a narrow street with me, near dying horses, dogs, and broken houses, when my servant found and saved us. As my parents could not be on the ground, they with all the family were obliged to save them in a ship where they spent about ten days. The earthquake is said to be the greatest of all and to have destroyed over fifty thousand of the citizens. After this terrible one, small vibrations did not cease, throughout the whole year. Some years later cholera dysphixia visited the city. It is said that, during this time, the officers of the city could not count the number of the citizens who were dead every day, and that a church, called [Sunichi?], where the dead were burnt up and buried, begun to catch fire, an account of the oil of man’s bodies. But fortunately my family did suffer neither the earthquakes nor the cholera. In my sixth year, my father obtained, for my education, a kind appointment of to the Chinese school. But nothing could be more suitable to me then the [line?] of the juvenile amendments. After having lived seven years in Osaka, I, together with my family, went to Hamamatszu, in the province of Totomi, which is in the midst of Tokaido and is about 73 miles from Osaka. Though I did not care about fencing, riding _, I spent most of my time in the Chinese School, which was supported at the Royal expense, in order to educate youth. In my 12th year, I was ordered to attend my former master, who, at this time, just returned from Tokio. In the war, 1867, though my master belonged to the side of the emperor, my father attended to the neither party and I, with him, lived in a village of a good ___ without any particular business till 1867. In the 7th month of the year, I, with my family, again went to Kadzusa. There I was obliged chiefly to attend domestic affairs, because my father was imprisoned, on account of the betraying him of some wicked persons to my master. One of the curiosity of this province is that there is no stone and people are obliged to buy it however small it is. The reason why my father was imprisoned was that, early in 1835, he, having understood, the Europeans are the civilized people, and determining, we ought to manage their best customs, art, sciences, went to Nagasaki to learn Dutch, and when he was there about three years, he made many cannon and other military instruments, after the model of those often Europeans, though there was at this time no specimen and he was obliged to make them entirely from books. After his returning home, he especially attended to the financial affairs of the House of Inouye and also to dismiss wicked officers who educated my young master to be a fool. So you know, at this time, each Daimio exercised an entirely arbitrary authority through many unwise officers, my father was finally obliged to be forced into the unreasonable custody. In 1870, when whole Daimios in Japan were abolished, he received an appointment from Daijokan and I came, with him, to Tokyo. Next year, I finally entered into the school, as Koshinsei.

T. Okamura

-

OKAMURA TERUHIKO 岡村輝彦 (1855? – 1916)

OKAMURA TERUHIKO 岡村輝彦 (1855? – 1916)Judge and lawyer of Meiji-Taisho Japan. He was born in Hamamatsu and studied Western Learning and foreign languages at a young age. In 1870, he entered Daigaku Nanko, then studied law at Kaisei Gakko from 1874. From 1876-1881, he studied at Kings College in London. Upon return he served as the judge of the Court of Appeals. He, along with Kikuchi and others, founded the Chuo University.

Also read his “First Impressions of Foreigners.”

-

Okamura grew up in Osaka and Hamamatsu during the reign of the Tokugawa shogunate. In his autobiography, he discussed the many hardships faced by the people of Japan during his childhood, particularly during the decline of the Tokugawa. Earthquakes and famines continued to bash Japan, killing thousands of people. Afterwards, the price of goods skyrocketed, sending many people, even those in the middle class, into poverty. On top of that, a new comet passed over Japan which was thought to be the worst augury by the religious class.

In addition to the natural disasters, cholera swept through Japan, killing many more people. At the age of six, his parents put him in a Chinese school until he turned twelve. For reasons associated with political affiliations and his education, Okamura’s father was imprisoned. A contributing factor of his imprisonment was that, in early 1835, he went to Nagasaki to learn Dutch from the Europeans. At this time, the overall sentiment of the Europeans and Western world were still very negative, and their master did not approve of this journey.

Okamura interjects his autobiography with a harsh critique of the samurai class. From Okamura’s essay, we saw that his view of Japanese politics is very critical, and that motif perseveres through this autobiography. One of the greatest faults in the life of the samurai was their mannerism. Okamura explains how they lived on the premise that “the soul of the Samurai is the sword.” Military duties that involved this sword became the primary objective of the Samurai, and being versed in academics fell into the background. They did not learn to read or write, and this was problematic because the upper class was not regarding education as important. They regarded mathematics as a subject for the merchants, forcing academics into the middle class. Samurai also started to abide by the new Kirisute-gomen act, which gave them permission to kill any man who they suspected, even falsely, of committing a wrongdoing toward them. This cast a shadow of fear over the lower classes and drew a greater disparity between the people of Japan.

Throughout his youth, Okamura endured many hardships, alongside which the structure of Japan crumbled and was slowly being rebuilt from the ashes. The disparity between classes only increased due to the natural disasters that rummaged Japan and the economics that crippled the lower classes.

-

Okamura begins his essay providing context of the time period he grew up in. He states that when he was born in 1855, the Tokugawa government was undergoing substantial changes. He notes that because Feudalism still existed at the time, class distinctions and the arbitrary policies of each Daimio gave way to largely varying customs and manners throughout Japan between different groups of people. Focusing on the customs of the upper class groups of Japan (Kuge, Daimio, and Samurai), it is clear that Okamura himself was born into a fairly high societal rank, primarly interacting with other upper class Japanese. Several details from the essay specifically trace his background to the samurai class. For instance, he describes the habits of the Kuge and Daimio as, “their customs were feeble and womanly. For instance, all Kuge, even the men, formerly blackened their teeth, embellished their faces with white powder, Oshiroi, and did several other things which now our women do.” The detail in this description shows his familiarity with the two groups, yet the negative tone implies that he was not included in this group. Furthermore, later in the essay, when writing about the details of his life, he talks about the samurai class in a positive, admirable manner, stating that the Daimio were superior to the Kuge because “ they had, as their subjects, the gallant and brave feudal tenants, samurai, whose conducts were the basis of the manners of the present Japanese.” In addition, in describing his education, Okamura states that he learned fencing and riding, although he did not care much for these subjects. These observations align with the fact that most Japanese students studying in the United States were from the samurai class. Therefore, it is feasible that Okamura, a student of Griffis, was able to attend Rutgers College due to his status and wealth in Japan. (Wakabayashi note: Okamura did not attend Rutgers)

Interestingly, Okamura includes that his father was also interested in European arts and sciences. At the beginning of the text, he acknowledges that the Japanese first thought foreigners to be barbarous. However, he states that in 1835, his father expressed the belief that Europeans were civilized, and that it would be beneficial for the Japanese to learn their customs. Okamura mentions that his father went to Nagasaki to learn Dutch and designed military instruments modeled after those from the west. As many Japanese students like Okamura came to the United States to learn about western arts, sciences, and military technologies, it is reasonable that Okamura’s father influenced Okamura’s studies at Rutgers College.