This Spring, the United States Supreme Court would decide, in Missouri v. McNeely, whether police can forcibly draw a blood sample from a suspected drunk driver without first obtaining a warrant. As it turns out, the history of testing for alcohol intoxication in the United States can be traced back to the Center’s Yale days. Constitutional safeguards were partly responsible for shaping the research trajectory in the early years of the alcohol studies movement.

This Spring, the United States Supreme Court would decide, in Missouri v. McNeely, whether police can forcibly draw a blood sample from a suspected drunk driver without first obtaining a warrant. As it turns out, the history of testing for alcohol intoxication in the United States can be traced back to the Center’s Yale days. Constitutional safeguards were partly responsible for shaping the research trajectory in the early years of the alcohol studies movement.

The first person to measure alcohol concentration from body fluids was Erik M. P. Widmark, a Swedish chemist, in 1914. While the “Widmark Micromethod” spread through much of Europe in the 1920s and 1930s and became an established forensic test, the United States still relied exclusively on behavioral evidence, which, while frequently compelling, was not dispositive. This is explained in part by the Prohibition-era disinterest in alcohol science. Even so, a major reason the United States lagged behind Europe in forensic alcohol testing was its unique, constitutionally enshrined protections, in particular the Fourth Amendment right against unreasonable searches and the Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination.

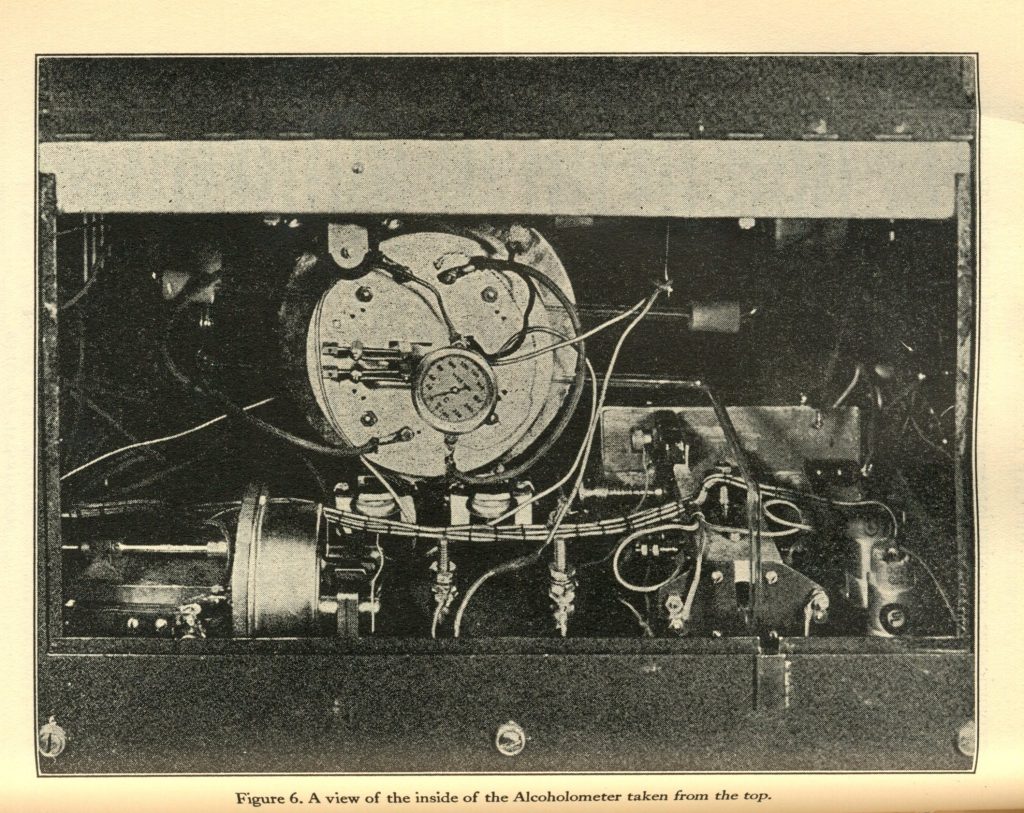

It wouldn’t be until the late 1930s when Americans, waking up to the treacherous combination of intoxication and driving, began seriously experimenting with breath-alcohol analysis, which was seen as less intrusive than testing blood. The Center’s own Leon Greenberg (1907–1985) was primarily responsible for inventing the Alcometer in 1941. The portable machine was one of three “first generation” breath-alcohol analysis devices that was introduced at the time, along with the Drunkometer and the Intoximeter. (Unfortunately for Greenberg, the Drunkometer, invented in 1931 by Indiana University’s Rolla N. Harger, lays claim to the first breath-test instrument used in the field by police.) The Alcometer worked by mixing the alveolar air in one’s deep breath with iodine pentoxide. If there was alcohol in one’s system, the reaction released iodine, which when absorbed in a starch solution caused its color to change in proportion to the amount of alcohol present.

Despite being touted as a breakthrough, neither the Alcometer nor its two close competitors were used for very long. (Apart from concerns over accuracy and convenience, the Alcometer suffered from relying on an unstable reagent, iodine pentoxide.) All three devices would be quickly supplanted by the introduction of the Breathalyzer in 1954.

Treasures in the CAS Archive – a column of the CAS Information Services Newsletter (2007-2016) was dedicated to the new discoveries as the dormant documents and images resurfaced. The short paragraphs presented a few artifacts recently discovered and digitized.

–Originally published in the March 2013 issue of the CAS Information Services Newsletter. Written by Scott Goldstein.