Following up on the previous post about Humor in Alcohol Studies, let’s take a closer look at a few more language-related examples left behind by the two major figures, who defined alcohol studies, E. M. Jellinek and Mark Keller.

Language as the Source of Humor

In his unpublished amusing piece, The evolution of English spelling, Jellinek, talented in many languages, has fun mocking English orthography, especially the letter-to-sound correspondences, from the perspective of a native speaker of Hungarian, a language with highly consistent correspondences between the written symbols and significant spoken sounds. Non-native speakers of English out there, who had to learn basically TWO words for one (one for writing, one for speaking): you will be delighted to share the pain through his humor. (Click on the image to enlarge and read the short excerpt.)

In his unpublished amusing piece, The evolution of English spelling, Jellinek, talented in many languages, has fun mocking English orthography, especially the letter-to-sound correspondences, from the perspective of a native speaker of Hungarian, a language with highly consistent correspondences between the written symbols and significant spoken sounds. Non-native speakers of English out there, who had to learn basically TWO words for one (one for writing, one for speaking): you will be delighted to share the pain through his humor. (Click on the image to enlarge and read the short excerpt.)

Another entertaining article is Jellinek’s unpublished biographical dictionary, Who was who in Greek mythology, which rephrases classical legends in contemporary language. The text is pure delight to read and decipher for any mythology fan, as detailed earlier in Bunky’s Pantheon. Well aware of Jellinek’s mysterious life, the author of the previous post can’t help speculating whether jumping from Greek to Roman mythology mirrors the ease with what he changes identities, careers, names, and more.

What can we expect from a genius who sported multiple alter egos and named his lifelong ulcer “Habakkuk?”

Note: the full text of both of these masterpieces are available from RUcore courtesy of the Rutgers Digital Alcohol Studies Collection.

Nonsense verses

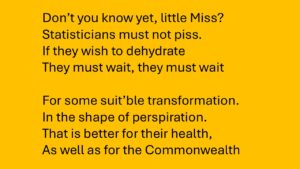

What’s a “poem” doing in a scholarly publication? Let alone this one? Jellinek was famous for his talent of grasping the essence of any issue, such as the lack of breaks at the Worcester State Hospital, where he worked as a biostatistician. When state employees were mandated to account for every minute spent away from their desk, Jellinek posted two of his nonsense verses on the department’s bulletin board. His efforts were unequivocally welcomed, especially by female staff. The message to management was so powerful that both masterpieces made it to an article detailing the research there!

What’s a “poem” doing in a scholarly publication? Let alone this one? Jellinek was famous for his talent of grasping the essence of any issue, such as the lack of breaks at the Worcester State Hospital, where he worked as a biostatistician. When state employees were mandated to account for every minute spent away from their desk, Jellinek posted two of his nonsense verses on the department’s bulletin board. His efforts were unequivocally welcomed, especially by female staff. The message to management was so powerful that both masterpieces made it to an article detailing the research there!

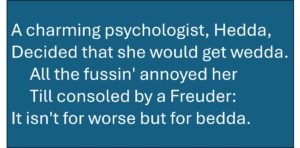

Very few of Keller’s nonsense verses survived, but there’s anecdotal evidence that he was just as a great wordcrafter as Jellinek in poetry as well. Once, when another researcher, Hedda Bolgar was leaving to marry a Swedish count, there was a contest among the staff to write a gift card message. Keller wrote his very first limerick, and won, although Jellinek pronounced it best, with his thick Hungarian accent, according to popular opinion. (Note: I tried, it works!)

Very few of Keller’s nonsense verses survived, but there’s anecdotal evidence that he was just as a great wordcrafter as Jellinek in poetry as well. Once, when another researcher, Hedda Bolgar was leaving to marry a Swedish count, there was a contest among the staff to write a gift card message. Keller wrote his very first limerick, and won, although Jellinek pronounced it best, with his thick Hungarian accent, according to popular opinion. (Note: I tried, it works!)

The Editor’s Smirk

To Your Health, with Jellinek’s alter ego

Who knew that reading the text in fading ink on yellowish paper can be so much fun? For the second and third time too!

Just like Jellinek was able to sneak in cameos of himself and his colleagues in the WHO cartoon To Your Health, Keller, the long-time editor of the JSA, ambushed the unsuspecting audience when he gave a hilarious speech here at Rutgers in 1979, at the celebration of the 1978 Mark Keller Award, presented to the best authors of the Journal.

Published later as De mentis editorus (“About the editor’s mind,” for those who missed high school Latin) in Medical Communications, Keller’s article is a full blown satire mocking the practices of scholarly publishing. Looking at papers submitted for publication from the journal’s perspective, he educates the audience by giving advice to all “who would like to be infallibly successful science authors.” He seems to have the answer to the big question every aspiring author has asked themselves a few times: “How do you get past by the dragon fire of the editor and the gnashing teeth of Referee A and the slashing claws of Referee B?”

Entertaining authors with hypothetical articles, Keller goes through the motions from selecting a journal to publish an article. He even admits that editors don’t want to publish negative results, that’s why there are 7,654,321 experiments with negative results unreported! “If you didn’ find out anything, who wants to read about it?” His absurd idea, double-spacing your manuscript for surefire acceptance, sounds eternal and 55 years later, Keller’s words still stand: you must learn to think like an editor! You want to get published? Mark Keller’s wisdom is for the win!

References

- Jellinek, E. M. (n. d.). The evolution of English spelling [unpublished]. Center of Alcohol Studies Archives, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Piscataway.

- Jellinek, E. M. (n. d.). Who was who in Greek mythology [unpublished]. Center of Alcohol Studies Archives, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Piscataway.

- Keller, M. (1979). De mentis editorus. Medical Communications, 7(3), 145-151

- Shakow, D. (1972).The Worcester State Hospital Research on schizophrenia (1927-1946). Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 80, 67–110.