The Project

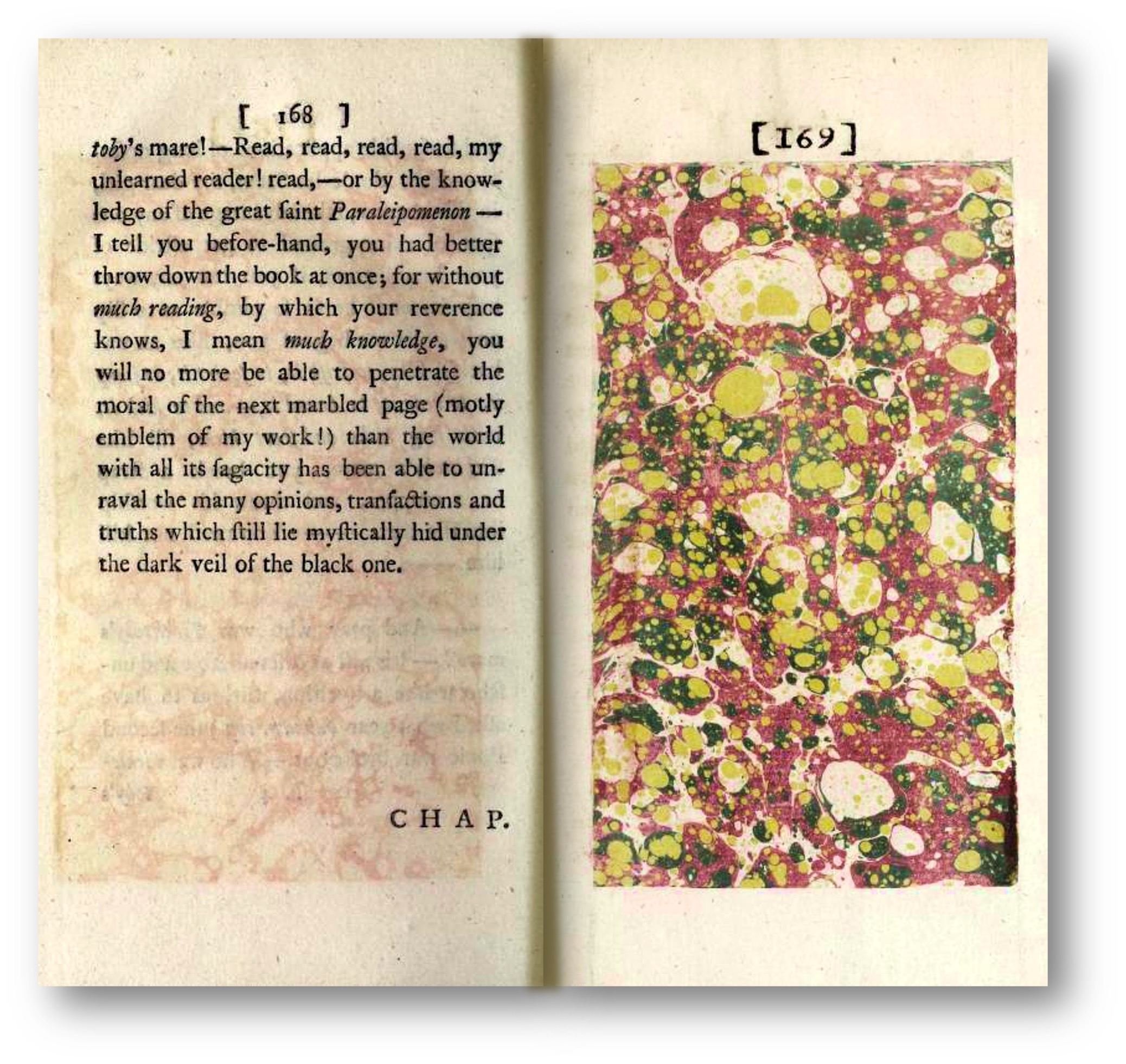

Smack in the middle of Laurence Sterne’s 18th-century novel Tristram Shandy is a single leaf of marbled paper. Sterne’s waggish narrator, whose “life and opinions” the novel is, calls that leaf “the motley emblem of my work.” That is where this project gets its name and its inspiration; the purpose of the Motley Emblem is to recreate that page, well enough that it could (almost) pass for an original. I say “almost” because there’s no intent to make it pass for genuine; the Motley Emblem isn’t a forger’s shop! The point is to meet the marbled leaf at its own level, gathering the knowledge it took to make it. This means making (at least) one. Since it was a mass-produced object designed for a book, it probably means making several hundred, in the proto-production line conditions of the British cottage system of manufacturing.

In the first place, then, marbling the motley emblem means learning the art of marbling, as it was practiced in London in the eighteenth-century. Marbling is done by preparing a liquid medium, called “size,” from water and a gelatinous gum that originates in Anatolia. Then liquid pigments are spattered on the size in droplets. A sheet is laid gently on the surface, and when that sheet is drawn away, it takes the colors with it. Sterne’s page adds the additional complexity that each sheet must be carefully folded to preserve the margins in their unmarbled state; also, both sides of the leaf must be marbled, by reversing the folds and repeating the marbling procedure. Every sheet will of course be unique, even if the procedure for successive pages is the same, since the slightest differences in the distribution of droplets or the mixture of the pigments produces a different arrangement of color.

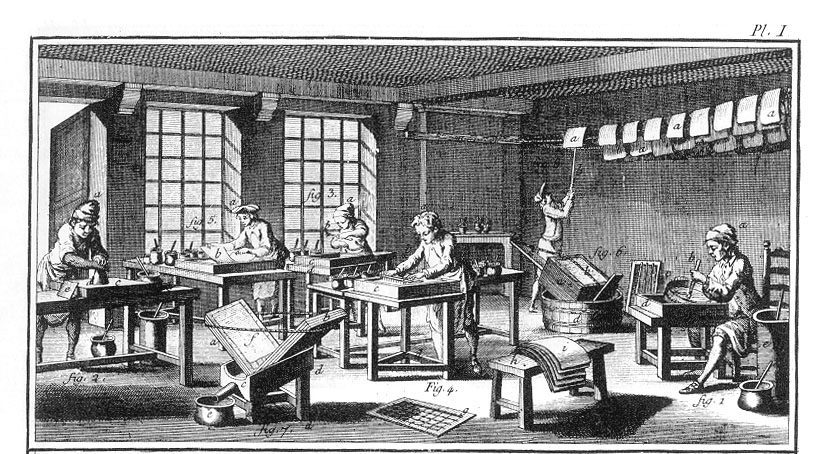

But the simplicity of the process, which is almost all an acquired knack of getting the correct consistencies and then flicking them dexterously with a brush, belies the huge body of knowledge and labor that precedes the moment when paper meets pigments. The colors were made by the “color-men,” and the brushed wound by the brush-makers, and reagents made by metallurgists or extracted by dyers—and so on. The body of labor in the marbled page is not the work of one pair of hands; it took an empire and an emerging design tradition to manage it.

So: in the second place, the colors must be made. Since the pigments of on Sterne’s marbled page were everyday pigments made prior to the revolution in synthetic colors of the late 19th century, it is not possible simply to buy them, as Sterne’s marbler undoubtedly did. They must be made from scratch, following the clues and surviving directions of eighteenth-century chemists. This means learning the practical chemistry of eighteenth-century colors, in order actually to extract dyestuffs from plant-matter and transforming them to pigments, or synthesizing colors directly from minerals. Much of the labor of the motley emblem, that is, happens in the laboratory.

Yet more, mastering Sterne’s marbled page has meant understanding the eighteenth-century arts of design, including the place of marbling in a history of British aesthetic criticism. Partly because of the complex war playing out between England and France, and partly because of the maturing of English manufactories, 1760 is often named as the moment when England’s design tradition first emerged as a competitor for European manufactures. Marbled paper was a part of this set of developments, one of the handful of commodities singled out for English manufacture, which implicates it in a tradition of thinking about aesthetic experience. While it would be technically possible to recreate an instance of the motley emblem without understanding its place in this discourse, a full accounting of the page in its place means recovering the reasons for its popularity, including what people might have admired when they viewed it. This means archival work, recovering an emerging design tradition and its place in aesthetic criticism.

So: there is laboratory work, and archival work, and labor in the workshop—in addition to other trades, like carpentry and brush-making. It’s a big task for such a little page. But there are reasons to believe that it isn’t hopeless. For one thing, Sterne’s marblers themselves were learning to marble while making the original marbled leaves, so their work is within reach of someone also learning the craft. What is more, the best account of eighteenth-century marbling was composed by an industrial chemist who was learning the trade alongside Sterne’s marblers—possibly from Sterne’s marblers themselves. That is, the description we have of eighteenth-century marbling is a description of the techniques employed by the creators of the original motley emblem.

Finally, it helps that the historical art of marbling, in the way that Sterne’s marblers practiced it, is still practiced in places in the Levant and the Near East. There, it is possible to study it from living masters, as, for instance, in the cool stone recesses of the Caferağa Madresesi, where works Tüzin Tirkyaki as part of women’s collective of cultural artisans. While recovering historical pigments and an historical aesthetic still means work in the archive and in the laboratory, the living knowledge of Sterne’s marblers still exists, passed down not in the archive, but the repertoire.

The goal of the Motley Emblem is a page indistinguishable from the original. But it is also a book, which will take the marbled page as its emblem and its title. In this book, as in Tristram Shandy, the marbled page will be an emblem for work. But this work will no longer be limited to Sterne’s labor in penning the novel, but of the work of the whole loosely reticulated network of persons, crafts, and things that brought the page into being—of which Sterne was just the vanishingly small spark who thought to commission it in the first place.