Why This Matters

The SHORT VERSION

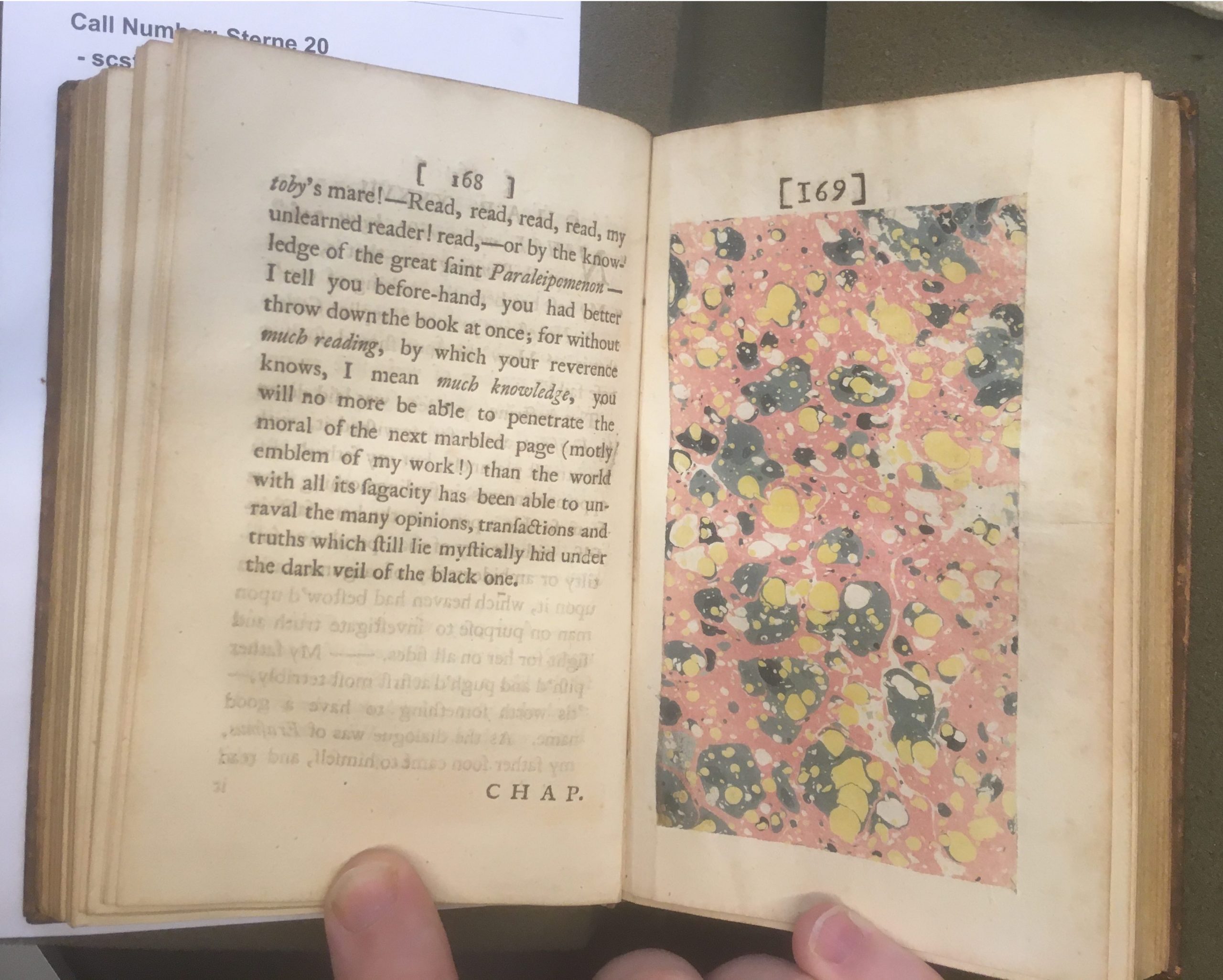

Hardly larger than a playing card, the motley emblem is nevertheless as large as the first global empire. Recreating it prompts an encounter with a global culture in its happening, with the craft disciplines, the asymmetrical systems of production, and even the intellectual and social practices, which account for its form and appearance. No single person who made the motley emblem could have known everything that was represented there: not the person who gathered the reagents, nor the ones who shipped and resold them, not the ones who mixed them to paint, nor the one who combined them on paper, nor even the author who called for the image in the first place. Getting as close as possible to that total knowledge is my task. Accomplishing it means recreating this complex object of luxury consumption as a window into a transformational moment in human history.

The SOMEWHAT LONGER VERSION

As recently as 1985, one scholar was right to say that little attention had been paid to Laurence Sterne’s marbled page. It had been omitted from most recent editions of the book, and criticism tended to overlook it as well. But since then, it is fair to say that more ink has been spilled about the page, than pigment was spilled to make it in the first place. There exists a book-length monograph on the subject, and more articles and chapters than could be counted on the fingers of both hands. In 2010, to mark the sesquicentennial of its publication, the Sterne Trust commissioned a book of 169 artists’ interpretations, which included a few instances of marbling by artisans in the technique’s modern form. And this is not even to mention all the prose lavished in blogs and grant proposals and published reflections on the motley emblem, which together constitute a surprising wealth of work on this single, unlettered page.

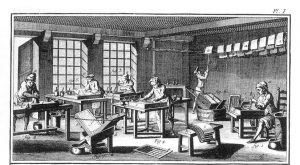

But no-one has asked the question about the conditions which made the page possible. It has never been asked whose work the motley page is an emblem of. That is, Sterne calls the page the “emblem of his work,” but it wasn’t his labor involved in making it; it wasn’t his work. Someone else provided the hands and the time and the skill and repetitive acts—some man or woman, or team of men and women, who spattered pigments on a liquid medium, then took it up on paper, a process partly recorded in Diderot and D’Alembert’s Encyclopedie (in a print engraving performed by yet other hands). But even that artisan or studio did not make the colors, nor lay the rag and pulp to make the paper. They did not harvest the botanicals which made the pigments, nor mine the minerals, nor transport those plants and stones across land and ocean, nor transform them into the colors that wound up on Sterne’s page. That took a whole, asymmetrical system of production and consumption, the first global maritime system of trade which would develop, some say metastasize, into the British empire.

I began this project in the same way everyone else did, I mean everyone else who has lavished thought on Sterne’s orphic page. I began by thinking of the page as a reflection on something about Sterne’s digressive style, or its associations with non-figurative art, or its alliances with systems of chance and contingency. I will have some things to say about this in my chapter on ink. But I have wound up thinking of the page as that empire’s still life, of the countless hands which collected, then passed on mineral and vegetable simples to make one striking aesthetic experience. Or: not a still life, but something like its cam-shaft, a wheel within its living wheel, for the page isn’t just an image of Britain trembling on the verge of becoming the first global superpower, but the sort of thing that caused its whole shuddering machinery to lurch into action in the first place. Part of what the Empire sustained was luxury consumption, which included things like the novel. It is just that this page, from a novel, also happens to put the fruits of empire conspicuously on display. That’s what the marbled page is an emblem of; it is an early emblem of globalism, if we learn how to read it.

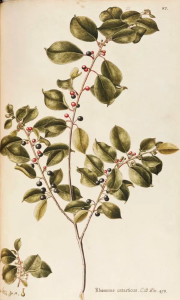

And learning to read it has meant learning to make it, since making something prompts us to meet it at its own level. Partly, this is a task of recovering that sort of knowledge which is known as “tacit.” Tacit means silent; tacit knowledge is unspoken, the stuff that is a trick of the hand or of the wrist, the meddling with materials which comes through careful application and the master-student relationship formerly called an apprenticeship. Simon During calls this sort of re-creation a “mimic toil,” and notes that the eighteenth century was the first time that people delighted in this sort of historical work. But, partly, making the marbled page has meant retracing or recultivating trade routes put in place in the two events differently called the “commercial revolution”: the 13th– and 14th-century modernization of trade in the Mediterranean, and the 17th– and 18th-century opening of maritime global trade networks. Though air freight has opened new modes of shipping, the sources of the materials which wind up on the page remain largely the same: Rhamnus cathartica from Anatolia, Caesalpinia echinata from Brazil, and so on. The Motley Emblem is a global emblem. That is why this matters.

The MUCH LONGER VERSION

Eventually, the Motley Emblem will wind up in a book of its own—a book of six chapters, following the order of the colors on the page: an paper history of the marbler’s art and its sources, with chapters on red, green, yellow, gall, and black ink. I am not interested in the loose historical resonances of color, a project in any case explored by people like Michel Pastoureau, author of books bearing the titles of each of the colors on Sterne’s marbled page. I am interested in a material history of an aesthetic experience, of the pyramid of people which were involved—some by choice, some by coercion—in the making of the motley emblem. Embedded in Sterne’s page, motley emblem of his work, is a surprisingly coherent narrative about art and the materials of its moment. The success of this project will be a leaf indistinguishable from the original. But it will also be a new book, containing that leaf– which tells the story of the world that brought the originals into being.