Storytelling in scholarly communication is an art itself. Reading one overly technical text after the other calls for something else if one wants to keep sane: playing with the language through humor, irony, and even sarcasm. The best literary authors are famous (or infamous, it’s a matter of taste) for their devastating wits from Voltaire to Hašek to Douglass Adams, but what about scientists? Enter Alcohol Studies, way ahead of the curve as an emerging field in science in the 1940, proven by discovering the power of cats before social media.

Storytelling in scholarly communication is an art itself. Reading one overly technical text after the other calls for something else if one wants to keep sane: playing with the language through humor, irony, and even sarcasm. The best literary authors are famous (or infamous, it’s a matter of taste) for their devastating wits from Voltaire to Hašek to Douglass Adams, but what about scientists? Enter Alcohol Studies, way ahead of the curve as an emerging field in science in the 1940, proven by discovering the power of cats before social media.

Humor in the Archives

Processing the Mark Keller Papers often comes with the occasional laughter hard to withhold. Even if I had read most of these texts, they still make me chuckle. How can anyone in academia not smirk at this snide comment written by Keller, also called KELLER’S LAW, by his colleagues:

The investigation of any trait in alcoholics will show that they have either more or less of it.

Written in 1972 and republished several times, the short article comes with a summary, too! “Alcoholics are different in so many ways that it doesn’t make a difference.” Anyone who had the displeasure of listening to a vainglorious, stuck-up academic will immediately fall in love with this ancient-fresh style with a lot of attitude. But can you reproduce it? One must have a strong command of the English language to get published, but for this style, one also needs the talent to be able shift effortlessly between linguistic variations from formal to casual to intimate, the latter including jargon and inside jokes.

Language Buffs in Alcohol Studies

Jumping between registers of meaning in English is just one thing. Both polyglots, Mark Keller and E. M. Jellinek, were pretty comfortable jumping between languages, too. In their correspondence, Keller often used some Yiddish, closing it with the German goodbye “servus” at the end, while Jellinek, known to speak more than ten languages, frequently sprinkled his texts with a foreign word or two from any of those languages. You can do that to close friends, and only when are sure that they will also find it funny, instead of condescending or elitist. That is, they also speak that particular language. (Speaking from experience, you don’t have a huge audience, so you enjoy every opportunity to crack an interlingual joke.)

Their use of puns were infectious, spreading like wildfire among friends and family. Keller’s affectionate correspondence with Ruth Surry, Jellinek’s daughter is full of humorous code switching between various languages called “Engolish” and “Frangoliano” by them, a result of growing up multilingual. Jellinek’s second wife, Thelma Pierce Anderson, a budding mystery writer, was also fully on board with puns, calling Keller “Marcus Aurelius Keller.”

My personal favorite, by all means, is “genug gepissed,” Jellinek mixing the Yiddish word for “enough” into a phrase coined by him, with a rather self-explanatory meaning, to express his outrage over being ill-treated.

Bunky

Jellinek liked to be called “Bunky,” which, contrary to a popular myth, perpetuated by Mark Keller, does NOT mean “little radish” in Hungarian (just accept it from this native speaker, but I do have a citation below, too). He often signed his letters as Bunky. It started at the Worcester State Hospital in the 1930s. When Jellinek moved on to Yale, he brought quite a few people with him, such as Anne Roe and Vera Efron, and the nickname moved with them, too. Today “The Bunky” also refers to the Jellinek bust given out as part of the Jellinek Memorial Award, one of the top prizes in alcohol studies.

Bunkyana

The term “Bunkyana” was coined by Mark Keller to describe anything related to Jellinek, whether tangible or virtual. In their correspondence, Thelma Pierce Anderson and Keller collected quite a few seemingly insignificant tidbits to the image of Jellinek, which helped create a more nuanced idea of who he was, laying down the foundations.

It just so happened that the CAS Library had become a collection of Bunkyana. After presenting our groundbreaking Jellinek-research at the 36th Annual SALIS Conference (which made it to the Jellinek Wikipedia entry) in 2014 at Rutgers, addiction librarians from all over the world reached out with all kinds of weird Jellinek memorabilia, most of them are now in RUcore.

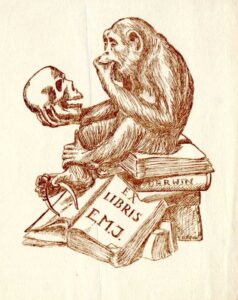

One of our own discoveries, Bunky’s bookplate is another joke, full of erudition and humor: an unorthodox 4×5-inch ex libris marked with the initials E.M.J. featuring a rather perplexed ape, which stares at a human skull while sitting on a book entitled “Darwin,” an obvious reference to Rodin’s Thinker and Darwin’s evolution theory. The “Monkey in the Library” as we called it, is a sketch drawn by Vera Efron from the indexing and abstracting services at the Yale Center of Alcohol Studies, later the Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies. She was another multilingual staff member with many talents, and one of the very first female information specialists in addiction science. She also illustrated books and pamphlets of early alcohol studies, some of them are rather funny (as much as the topic allowed, of course).

Stay tuned for more discoveries!

References

- Keller, M. (1972). The oddities of alcoholics. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 33(4), 1147-1148.

- Ward, J.H. (2014). E.M. Jellinek: The Hungarian Connection“, Substance Abuse Library and Information Studies: Proceedings of the 36th Annual SALIS Conference, 42-54.