Jewish Farming in the Garden State

From Toms River near the shore to Roosevelt outside of Trenton all the way south to Woodbine on the road to Cape May, generations of Jewish colonists farmed New Jersey from the 1880s until the 1960s.

Like Jewish farmers around the Americas, Eastern Europe and Palestine during these decades, the Garden State colonists were almost all totally new to the farming life, having worked before that mostly in commerce, the trades, peddling or even “living off the air” (luftmenschen in Yiddish). They almost all began their journey to the land in the mid-Atlantic region under difficult political and economic conditions somewhere in East or Central Europe.

The New Jersey story of Jewish farming began with the ill-fated Am Olam movement in the early 1880s, when the Alliance Colony was first founded in Salem County. Those humble roots grew in the coming decades into a major agrarianization project involving tens of thousands of immigrants, huge investments from Jewish philanthropic organizations, trials and errors on the land, the creation of long-lasting cooperative associations and the integration of Jewish colonists into the fabric of the Garden State.

Woodbine Colony Band, undated

Credit: Jewish Encyclopedia, 1906

With the founding of the Baron de Hirsh Agricultural School in Woodbine in the 1890s, New Jersey became the flagship for Jewish farming in North America. We invite you to explore specific colonies in the Garden State within the exhibit.

Allen Meyers, Southern New Jersey Synagogues: A Social History, 1880s-1980s.

Allen Meyers’ hand-drawn map of southern New Jersey is the most comprehensive rendering of the location of colonies in Salem, Cumberland, Cape May and Gloucester counties, which were home to most of the state’s Jewish farming communities. Starting in the 1930s and continuing into the Second World War, Jewish philanthropic organizations founded smaller communities in Central New Jersey, guided by a newly popularized concept of “agro-industrial” townships situated close to urban markets and integrated into booming egg and poultry production in the region. The Roosevelt Colony was one example of such an agro-industrial experiment.

Jewish chicken farmers, Millstone Township, undated

Credit: New Jersey Jewish News, June 16, 2014

Meyers’ map incorporates the following communities in southern New Jersey. Some, like Carmel, functioned as vibrant colonies for a few generations while others, like Ziontown, were smaller and shorter-lived.

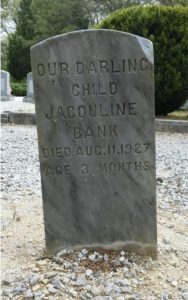

Times could be very hard in the first years of a colony, particularly for early colonies, while rural infrastructures remained underdeveloped. Harsh weather, poor sanitation, meager food, an absence of health services and pests all could take their toll on pioneering Jewish colonists as well as their non-Jewish neighbors in the New Jersey countryside. Vestiges of this suffering can be found in the colonies’ cemeteries, where the incidence of child mortality remained high into the early years of the 20th century.

Tombstones in the two Woodbine Colony cemeteries

Photos from 2021

Much can be learned about the colonies in southern New Jersey by looking again at Alan Meyers’ map and at the map below published in Joseph Brandes, Immigrants to Freedom, 1971. Overall, we see that philanthropic funders of Jewish farming had learned from the failures of the Am Olam movement in North America and the first hardships of Jewish colonists in Argentina. How so?

-

When they began purchasing farmland in southern New Jersey, the funders – like the de Hirsch Fund and the Jewish Agricultural Society – purposely established colonies in clusters. As we clearly see in the red circle in Meyers’ map, most of the south Jersey colonies were in close proximity to each other and situated within a ten-mile radius.

-

As we see in blue outline in Meyers’ map, colonies were founded next to railroad stations, connecting them to one another and the towns of Vineland, Millville and Bridgeton. Trains allowed low-cost access to markets for the colonies’ produce and easy travel for shopping, health, entertainment, recreation, employment and educational services.

-

These same rail lines connected colonies to major metropolitan areas. Philadelphia was a 38-mile trip from the settlement hub, New York City 125 miles away. Colonists thereby could quickly travel to their extended families, religious services and other needs in the “big city.”

-

For newer colonies in central New Jersey, trains and good roads allowed easy transportation to nearby urban centers like Trenton and Atlantic City.

Allen Meyers, Southern New Jersey Synagogues: A Social History, 1880s-1980s.

Credit: Joesph Brandes, Immigrants to Freedom

Among the surprises of Jewish farming in the Garden State is how long it lasted. Starting in the 1950s the national agricultural economy made it increasingly difficult for family farms to survive, especially when family labor had to be replaced by hired hands. These pressures became too much for many New Jersey farmers once their grown children left the colonies in search of other futures. Despite these obstacles, the chart below shows that Jewish farmers remained deeply engaged in New Jersey egg production until at least the mid-1970s.

Credit: Joan R. Barch, “Jewish Egg Farmers in New Jersey.” Master’s thesis, Northeastern Illinois University, 1976, page 84.

Beth Hillel Synagogue, Garton Road Colony, Deerfield Township, constructed in 1890s. Undated photograph

Credit: Hidden New Jersey

Holocaust Survivors in Garden State Colonies

Although reduced in population due to significant outmigration of colonists in the late 1930s, Jewish aid organizations like the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society revived the southern New Jersey colonies in the late 1940s by resettling Holocaust survivors and Displaced Persons from Europe in homes of families who had departed years earlier.

As the settlement organizations – like the Jewish Agricultural Society – knew, poultry farming worked particularly well for Holocaust survivors because profitability did not require previous farming experience or much capital. Rather, successfully raising chickens required lots of hard work, readiness to accept professional instruction and strict attention to detail. Luckily for everyone, at this time the Vineland region excelled on a national scale in egg and chicken production.

The recollections of Annette Greenblatt point to the important role that colonies, particularly those focused on poultry production, played in the absorption of Holocaust survivors into American life after the Second World War.

SI: What did they do once they settled in? Did they buy farms?

AG: Well, no, because her father was a rabbi. So, he was a rabbi here, but, most of the survivors, and we had about 300 families, as you probably heard, come in this neighborhood, … came because the Jewish Poultry Society purchased farms for them, and so, all of a sudden, … the lawyers and the doctors and the engineers became farmers, but, at least it got them into the country. … Many of them went back to their own professions, moved to the cities. … The perfect example is Miles Lerman, who, today, is president of the Holocaust [Society?] and who has done such a tremendous amount in the Jewish world, and many of them have been very active.

Click below to read the full transcript

Read More

While some survivors and DPs quickly left the colonies, most families remained for years. Within a short time they became integral to the local economy. Perhaps most noticeably, survivor-colonists formed the Jewish Poultry Farmers Association of South Jersey and a Mutual Aid Society in 1952, which other “veteran” farmers in the region then joined. For more on this aspect of the colonies, visit the “Cooperatives” page.

Like earlier generations in Alliance, most children of survivors left the colonies in their young adulthood in search of higher education, white-collar employment and other opportunities unavailable in rural New Jersey.

Abandoned chicken house, Epstein’s farm, Toms River, undated

Credit: New Jersey Jewish News, June 16, 2014

A Survivor Couple’s New Jersey Story

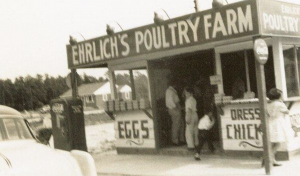

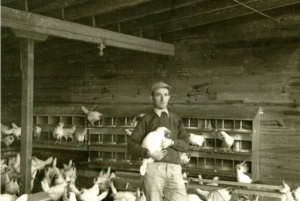

Born in Poland in 1918, Wolf Ehrlich, a survivor of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp, migrated to the United States in 1951. Wolf began his American journey together with his wife Hanna – a fellow Holocaust survivor from Poland – as poultry farmers in Egg Harbor, where they raised their family. The Ehrlichs later became successful business owners in the area and deeply engaged in Jewish communal life until they passed away in 2010 (Wolf) and 2018 (Hanna).

Click on the images below to view them in greater detail

Left: Roadside poultry stand, 1958 Right: Wolf Ehrlich in one of his chicken coops, 1956.

Credit: JewishGen.org

Some of the rural synagogues built in the southern New Jersey colonies stayed open from the 1960s into the early 2000s, with attendees from nearby towns or descendants from the colonies coming “home” for visits. Local Jewish communities in the area also maintained communal cemeteries over the years.

Jewish involvement in southern New Jersey farming life is undergoing a fascinating rebirth in recent years. Among these efforts is Alliance Colony Reboot, founded by a descendant of an original Am Olam communard, Moses Bayuk. This and other projects can be explored further on the New Generations page of the exhibit. (embed here the ACRe logo and link to New Generations page)

For more history on the colonies in southern New Jersey, visit the

Stockton University Alliance Colony Digital Museum