Early Zionist Settlement in Palestine

The creation of agricultural communes in North America by a few hundred Am Olamniks from the Russian Empire was not unique in the Jewish world. Rather, it happened in parallel to another small, but important, agrarian movement. Friends and neighbors of the Am Olamniks from Odessa and other cities in the Russian Empire also charted new paths in response to pogroms during 1881-82 and the Tsar’s antisemitic May Laws that followed in1882. Among those responses, Zionism coalesced as a political movement and some of its activists formed the Bilu [Hebrew acronym for “House of Jacob Come Ye and Let us Go Forth” (Isaiah 2:5)] and Hovavei Tsion [Lovers of Zion] movements, led by luminaries like Moshe Leib Lilienblium, Y.L. Gordon and Leo Pinsker. In 1882, Pinsker published a foundational Zionist text, Autoemancipation. Like members of Am Olam in North America, the Bilus and Lovers of Zion believed that utopian agricultural settlement would lead to a better future for Jews.

From 1882 to 1884, the first few hundred Zionist pioneers founded six semi-cooperative agricultural communities (moshavot), most of which later evolved into modern cities like Rishon LeZion, Petakh Tikvah, Gedera, and Zikhron Yaacov. By 1903, there were 28 moshavot in Palestine. The physical hardships in Palestine at the time meant that many of the original Bilus returned to Russia and turnover in the moshavot was very high. But this idealistic wave of agricultural settlement launched what became Israel’s farming miracle led by the kibbutz and moshav movements.

“A map from 1911 marking (with triangles) the moshavot in Palestine.”

Religious Zionists in Europe began to form their own kibbutz movement in the 1930s, approximately a decade after the start of secular kibbutz movements. The approximate locations of the religious kibbutzim appear below on the letterhead of the Religious Kibbutz Movement in 1946. Some of the border kibbutzim were overrun, and many members killed, by Arab armies during Israel’s War of Independence. Others relocated after the war. Today the Religious Kibbutz Movement includes 23 kibbutzim and other communities.

Credit: Archive of the Religious Kibbutz Movement

A typical kibbutz in its infancy. Kibbutz Yavneh , 1943

Credit: Archive of the Religious Kibbutz Movement

Unlike the failed Am Olam communes in North America, the moshavot survived and eventually thrived in Palestine because of the philanthropic aid and administration of Baron Edmund de Rothschild (1845-1934), starting in 1883, joined later by Baron de Hirsch’s Jewish Colonization Society. These philanthropists did not prioritize Jewish statehood. Rather, they invested vast sums in the belief that the future of Jewish life in Palestine depended on sustainable, profitable farming. The Rothschild/de Hirsch philanthropic partnership facilitated the purchase of farmland, the professionalization of agriculture and the founding of dozens of communities and towns in the Land of Israel before 1948.

Click on the images below to view them in greater detail.

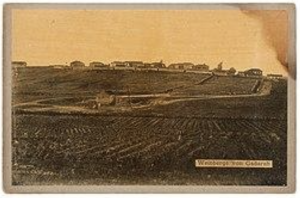

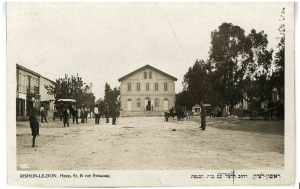

Left: Gedera, late 19th century Right: Rishon LeZion, 1890s

Baron Edmund de Rothschild and his wife visiting Zikhron Yaakov, Palestine, circa 1914.

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

In 1935 the fledgling Palestine Film Company released a publicity film “The Land of Promise,” the first “talkie” produced in pre-state Israel.

First screened for the public in Berlin in 1935, “The Land of Promise” was shown extensively in the months and years that followed. Jewish troops serving in Allied armies saw it during their service in the Second World War. In the early years of the State of Israel “The Land of Promise” screened frequently in transit camps for new immigrants en route from Europe or recent arrivals from Muslim countries. The kibbutz scenes were shot at Mishmar he-Emek.