Often overshadowed by stories of success and tragedy, agricultural cooperative associations in modern Jewish farming have always been pivotal, particularly in formative stages of colonies. In some former colonies, signs of their agricultural cooperatives remained long after the last colonists stopped farming.

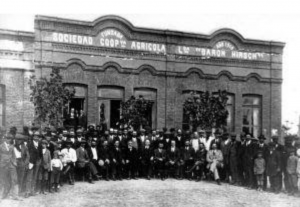

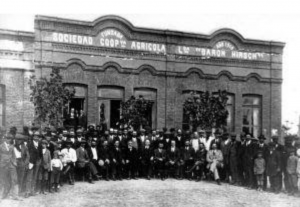

Baron De Hirsch Cooperative Agricultural Association

Rivera Colony, Argentina, founded in 1905

Photographed 1920s

Credit: AMIA

Agricultural Cooperative organizations characterized Jewish farming life in all of the major settlement projects out of both necessity and preference of the support agencies. What brought philanthropic organizations, led mostly by archetypical western capitalists, to promote cooperativism in Jewish agricultural colonies all over the world? First, the philanthropists realized that only through cooperative organizations could the lack of previous farming experience and lack of personal assets among new colonists be quickly offset in a cost-effective way. This meant technical instruction from agricultural experts, purchasing and marketing, as well as local credit had to be delivered through cooperative structures.

From the days of Baron de Hirsch in the 1880s onward, all of the support organizations insisted that low-interest mortgages be repaid by colonists on reasonable schedules. In short, agricultural cooperatives were not meant to be a new type of alms. The funders of Jewish agriculturalism – three of whom appear below – firmly believed that cooperative associations made possible the productivization of Jews and the sustainability of philanthropic organizations.

Left: Jacob Schiff, 1847-1920, international financier and funder of early Jewish farming colonies in the United States

Middle: Felix Warburg, 1871-1937, member of prominent banking family and promoter of Jewish agricultural resettlement projects in Europe and Mandatory Palestine.

Right: Julius Rosenwald, 1862-1932, founder of Sears, Roebuck & Co., renowned philanthropist and funder of Jewish agricultural settlement.

United States

In 1912, the General Manager of the Jewish Agricultural and Industrial Aid Society, Leonard G. Robinson, wrote:

“The most remarkable feature in the evolution of the agricultural movement among the Jews in the United States is the development of the spirit of self-help and cooperation. The Jewish farmers have learned the advantages of organized endeavor, and their efforts at mutual self-help and social and educational betterment are being well repaid… Their meetings are made occasions for picnics, festivals, and other social gatherings for the wives and children of the farms. They are looked upon as models by the non-Jewish farmers in the vicinity.”

What did Robinson know that most other Jewish leaders did not? By 1908 Jewish colonists in the United States had founded four cooperative associations; in 1912, that number had risen to 48.

Robinson then observed:

“With a number of organizations composed of men of the same blood, having suffered the same hardships, possessing the same ideals, with interests in common, and the same problems to solve, it was but a natural step that they should wish to get into closer relations with one another. Samuel P. Becker, a retired Jewish farmer of Hartford, CT, started an agitation for a union of these associations.”

Becker’s vision became reality: he served as the first president of the Federation of Jewish Farmers of America upon its founding in 1909.

Leonard G. Robinson, undated

Credit: Library of Congress

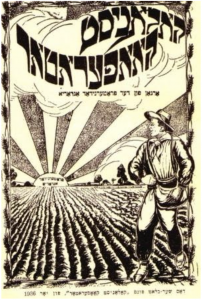

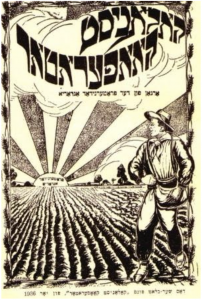

A booklet from the inaugural meeting of the Federation of Jewish Farmers of America, 1909. The Federation later created a purchasing coopertive for its member colonies.

In 1911 the Jewish Agricultural Society (successor to the Jewish Agricultural and Industrial Aid Society) deepened its investment in cooperativism by offering $2 at two percent interest for every $1 collected by local credit unions. Ten such credit unions came on line by 1912. That year Leonard Robinson observed, “The Credit Unions have endowed their members with a high sense of mutual responsibility, and have stimulated them to further effort in the direction of cooperation and mutual self-help.”

Decades later, Holocaust survivors and Displaced Persons who had emigrated after the end of the Second World War from Europe to colonies in the Garden State established in 1946 the Jewish Poultry Farmers Association of South Jersey. Their Association went on to establish a Mutual Aid Society in 1952. Shortly thereafter, “veteran” Jewish farmers from the area joined the Society. Lauded widely by professional groups, the Mutual Aid Society provided small, interest-free loans to its members.

The Cooperative Colonist journal, 1936

Published by the Jewish Agrarian Fraternity, Argentina

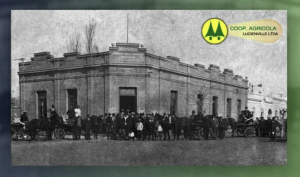

The story of Jewish agricultural cooperatives in Argentina began with Leon Nemirowski, a young administrator employed by Baron de Hirsch’s Jewish Colonization Society (JCA) who worked in the Lucienville Colony. Evidently without pre-approval from his superiors, Nemirowski opened a mutual aid society in Lucienville in 1900, naming it Primera Sociedad Agricola Israelita. The Society included local Jewish and non-Jewish farmers. More than a century later, it still operated in Lucienville but without Jewish members.

.

.

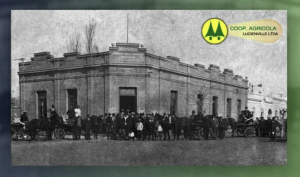

On the left, the opening celebration for the Sociedad Agricola Israelita in Lucienville, the first Jewish Agricultural Cooperative in Argentina, 1900. Credit: AMIA

On the right, more than a century later, the Lucienville Agricultural Cooperative, still active in its original building, 2010

Impressed by developments in Lucienville, the JCA opened cooperatives in many of its Argentine colonies, starting in 1904 with the Fondo Comunal at Clara Colony (Entre Rios State). Eventually the Fondo Comunal marketed half of produce grown in the area and served as a cooperative purchasing agency. It expanded to cooperative credit in the 1920s, operating into the 1950s.

Click the images below to enlarge them

The outside cover and introductory page from the 1957 pamphlet celebrating the 50th Anniversary of Fondo Comunal. By the year of the pamphlet’s publication, almost no Jews remained in the Entre Rios colonies.

Credit: Facebook page of Entre Rios State, Argentina

Soviet Union

Like its counterparts in South and North America, the Jewish agricultural project in the Soviet Union relied heavily on cooperative associations from the start of resettlement in Crimea and southern Ukraine in the early 1920s. And like Jewish farmers in the Americas, the support agencies – headed by the Agro-Joint – led Jewish colonists in the USSR toward cooperative structures.

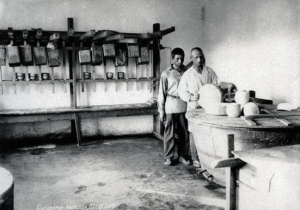

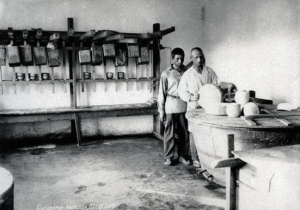

Office of the Agricultural Cooperative in the Lvova Colony

Kherson Province, Ukraine, 1920s

Credit: Beth Hatefutsoth Visual Documentation Center & JDC Collection

That high rate of cooperatives helps explain why Jewish colonists in the USSR suffered less from Joseph Stalin’s policy of forced collectivization of Soviet agriculture in the winter of 1929-1930 compared to non-Jewish peasants. While the colonies henceforth were called kolkhozes (Russian for “collective farms”) and some had to change their names from Hebrew (like “Herut” or “Avodah”) to conform with Soviet laws, the preexisting cooperative structures in Jewish colonies meant that their farm economies changed relatively little from forced collectivization and Stalinist terror against individual colonists was rare.

A cheese-making cooperative in the Novaia Zaria Colony, Crimea, 1931.

Credit: JDC Archive

Israel

Without agricultural cooperative associations one could argue that the agricultural miracle of Israel would never have happened. Unlike in other sites of Jewish agricultural projects in the world, in Palestine before Israeli independence in 1948 and afterwards, the farmers themselves were attuned to socialist ideology that uplifted cooperativism in theory and practice. Therefore, from the 1920s onward members of kibbutzim and moshavim did not need convincing from anyone to form or join cooperatives; rather, it was a natural process.

Perhaps the most well-known of these cooperatives is Tnuva, the Central Cooperative for the Marketing of Agricultural Produce in Israel. Formed by kibbutzim in 1926, Tnuva remained under kibbutz ownership until 2008.

Left: Tnuva Dairy Plant, Tel Aviv, late 1920s

Although Israel’s economy rapidly privatized starting in the 1990s, agricultural marketing cooperatives are still common.

Among the larger of these is Hevel Maon Enterprises, located in the western Negev desert. Hevel Maon (also known by the abbreviation “YAHAM”), founded in 1956 by ten local kibbutzim, sorts, packages and markets to the world fruits and vegetables harvested from the farms in the Negev.

Left: A hi-tech potato sorting system on the production floor, YAHAM

Click on the image below to view

a Hebrew-language Hevel Maon marketing film

YAHAM products for sale in Israel’s domestic market

.

.