The Jewish settlement experiment at Mizpah, Atlantic County, New Jersey, did not result in a sustainable Jewish colony. But the short story of Mizpah does offer insights into the realities of the times.

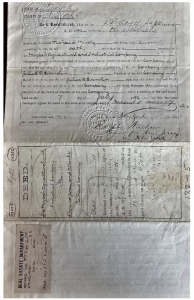

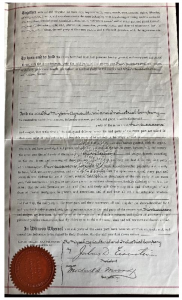

In 1892, the Mizpah Agricultural and Industrial Company signed a deed from the State of New Jersey for 1.5 acres of land in Hamilton Township, purchased from the West Jersey and Atlantic Railroad Company. Two men signed the Deed on behalf of the Company: Julius Eisenstein (President), an Orthodox Polish Jew who had emigrated to New York City in 1872 and Michael D. Mirsky (Secretary) of the Commune/Company.

Click on the images below to view them in greater detail

Above are two sides of the 1892 Deed for Mizpah.

Credit: Arnold and Deanne Kaplan Collection of Early American Judaica, University of Pennsylvania Libraries

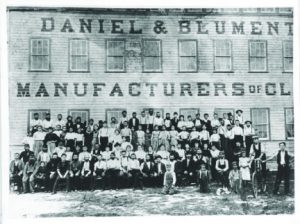

The Deed of 1892 declared that the Mizpah Agricultural and Industrial Company intended to establish a Russian-Jewish commune. This would have, on its surface, made Mizpah similar to other Jewish colonies founded at the time in New Jersey. But instead of philanthropic organizations, Mizpah’s primary investor was a clothing manufacturer – Blumenthal and Daniels – who wanted to build a factory town adjacent to an existing railroad line. They wanted cheap labor from recently arrived poor Russian-Jewish immigrants currently living in squalor in New York City and in Philadelphia.

All signs are that Eisenstein served as an idealistic front man for the factory owners – Blumenthal and Daniels – not understanding that they sought only profit. For his part, Eisenstein believed in the potential reconstructive power for Jews of an agro-industrial community. Eventually Eisenstein cut ties with Mizpah and emigrated to Palestine, where he became a noted translator, scholar and polemicist.

Left: Julius Eisenstein, 1854-1956

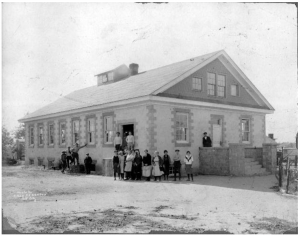

Unlike most Jewish colonies established in the Garden State, its founders never intended for Mizpah to be based on farming because the surrounding land was too swampy. So, it seems that the name of the company on the Deed (Mizpah Agricultural and Industrial Company) did not reflect the factory owners’ intent. Rather, it’s founders wanted to construct a model factory town where families had to buy their plots individually from real estate agents. Because of its non-agricultural character, the De Hirsch Fund decided not to invest significantly in Mizpah; other benefactors had to be found to support the families in the first years after settlement.

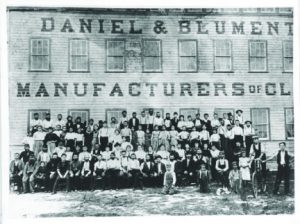

Daniel & Blumenthal Workers

Credit: PJAC via the Sam Azeez Museum of Woodbine Heritage at Stockton University

The Mizpah commune reached its maximum size of about 25 families in the early 20th century. At the time, several small clothing factories operated there and residents also dealt in piece work. Mizpah consecrated a synagogue in 1895 and also had a post office. But lacking financial backing, by the early 1910s the clothing workshops in Mizpah moved to Woodbine with many of the original settlers following them or moving to nearby Atlantic City. Around the same time, some of the original Mizpah members moved to the Carmel Colony near Alliance. With few families left, the Mizpah synagogue closed around 1914 and the remaining Jewish families continued solely as individual residents, not as commune members.

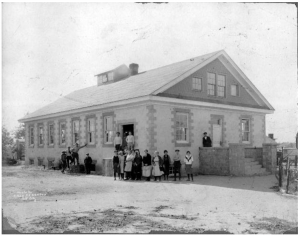

A clothing factory constructed in Mizpah.

One of Mizpah’s main streets is still named DeHirsch Avenue, running directly from the railroad station, which had been a main reason for establishment of the commune in this location.