The now-forgotten stories of early Jewish farming colonies in North America began as little more than a historical footnote in the middle decades of the nineteenth century. In 1820 a Jewish journalist, newspaper editor, playwright, political activist and communal leader, Mordecai Manuel Noah (1785-1851), purchased approximately 17,000 acres of land on Grand Island in the Niagara River, near Buffalo, New York. Noah wanted to settle Grand Island with Jews from all over the world in an autonomous city of refuge from oppression, violence and poverty. In 1825 he named the Island “Ararat,” with the intent that world Jewry would finance the migration and resettlement of its residents. Nothing became of Noah’s dream. But he did help inspire subsequent leaders and philanthropists toward ambitious solutions to the suffering of Europe’s Jews.

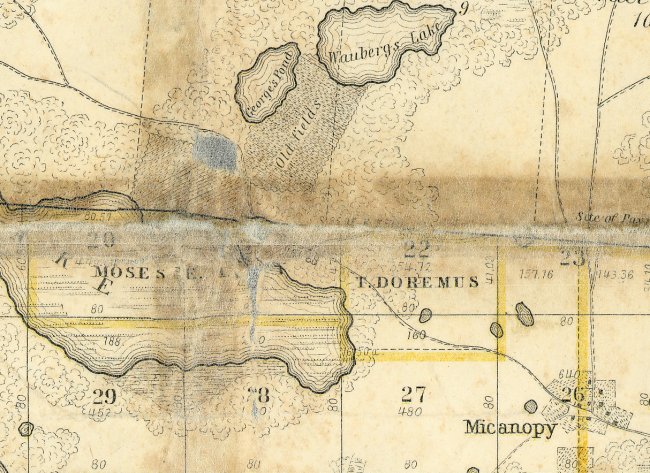

The next attempt at organized Jewish farming in the Americas also launched in 1825. This project was led by an affluent southern Jew of Moroccan descent, Moses Elias Levy (1782-1854). He intended to resettle European Jews in an agricultural utopia on a large tract of land in Alachua County, north-central Florida, which Levy named “Pilgrimage Plantation.” He managed to enlist about 70 German-speaking immigrants but the group probably dispersed before they made it to Florida.

For more details on Levy and the history of Pilgrimage Plantation, see this report by

The first Jewish farming community arose in 1837. An affluent Jew, Moses Cohen, bought land in the Catskills, near Wawarsing, where he established a colony called Sholem (or Shalom) and brought thirteen immigrant families from New York City. They started vegetable farming on the 484 acres Levy had purchased for the colony.

According to the website of the Kerkhonskson Synagogue in New York, the Sholem colony sat on 484 acres of poor farmland. Before long, some of the men moved to the local tannery while others fell back on traditional trades like tailoring and peddling. By 1842, only four of the original thirteen families remained. No traces are left of Sholem; its houses, dining hall and synagogue were lost to time, weather and fire.