United States

New arrivals to New York, Philadelphia or Montreal, to name just a few of the arrival cities, could seize upon opportunities offered by their countries. For example, Jewish immigrants (most of whom were Orthodox) could enlist in government programs designed to settle vast western expanses. In the United States, the Homestead Act of 1862 allotted immigrants a 160-acre parcel in the country’s interior on condition that they cultivate the land for five years or buy it outright. A half century later, in 1916 the Federal Farm Loan Act provided homesteaders loans on favorable terms.

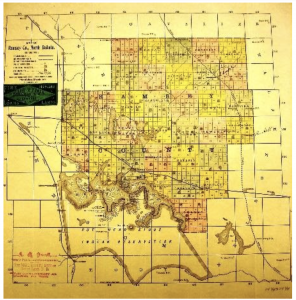

Map of Ramsay County, North Dakota, illustrating the homesteading grid of government allotments, circa 1890. In 1886, several Jewish farming families relocated to Iola (Cleveland hamlet, just above the center of Ramsay County). These families had previously been members of the failed Painted Woods colony, Burleigh County, North Dakota. The hardships and joys of life in Iola are captured in Rachel Calof’s Story: Jewish Homesteader on the Northern Plains, published in 1995.

Credit: Map Division, New York Public Library

Rachel Calof’s Story: Jewish Homesteader on the Northern Plains

Jewish farmers settled alongside much larger religious and ethnic communities. At its height between the world wars, the proportion of Jewish farmers in North America was nearly eight percent of all Jews on the continent. The vitality of these farms hinged on the same economic and environmental factors as their non-Jewish neighbors. So, a commodities market crash in the early 1890s devastated fledgling Jewish colonies. The 20th century began with around 1,000 Jewish farmers in America. By 1910, this had risen to 3,000-5,000 families. In 1925, the number had reached 50,000. In 1927, there were 80,000, and by 1937, the number had risen to 100,000.

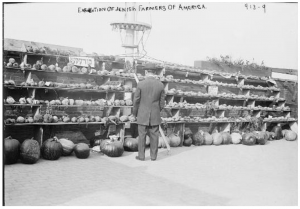

Formation of the Federation of Jewish Farmers of America in 1909 by thirteen separate Jewish farming organizations reflected this growth. That same year the Federation organized a national Fair and Convention in the Lower East Side of Manhattan. At least 50,000 people came to see the 952 entries from 225 exhibitors from as far away as North Dakota. Over time, the Federation expanded to include 63 local Jewish agricultural societies in eleven states.

An exhibit at the 1909 Federation Fair.

Credit: Library of Congress

Two sides of a medal awarded to a cabbage farmer at the 1909 Fair.

Credit: Library of Congress

A booth at the fair featuring vegetables and fruit, grown in the colonies.

Credit: Library of Congress

A booth at the fair featuring corn stalks and potted plants crown at the colonies

Credit: Library of Congress

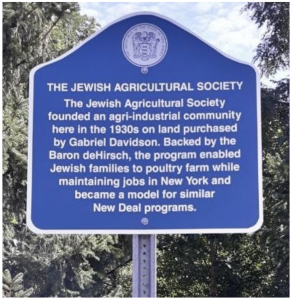

In 1933, the director of the Jewish Agricultural Society, Gabriel Davidson, calculated that Jewish farmers in the United States owned a total of 1.5 million acres worth approximately $150 million. Davidson embraced the restorative potential of agro-industrial colonies to address the unique economic and social challenges facing Jews and other working-class communities during the Great Depression. His commitment is captured on the sign below at the corner of Davidson & Davidson East, on the Busch Campus of Rutgers University.

Google Maps location of the dedication sign in the photo shown above.

Coordinates to sign location: 40°31’30.2″N 74°27’16.0″W

Photo: Prof. Gary Rendsburg, Rutgers University

At its apogee in the 1940s, what had begun as disappointing rural experiments in the 1880s had flowered into a significant part of Jewish life in North America, with tens of thousands of farmers in Jewish colonies in one hundred farming communities from southern New Jersey to northern California and from Saskatchewan to eastern Connecticut.

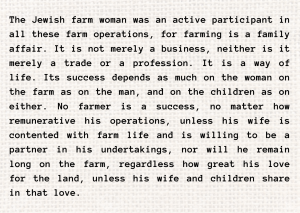

Mrs. Herman Levine, wife of the regional director of the Jewish Agricultural Society in Ellenville, New York from 1922-1945, observed:

Credit: American Jewish Historical Society Archive, I-80, box 83, folder 4

Abe and Martha Crystal on their poultry farm, Alliance Colony, New Jersey, undated.

Credit: Alliance Heritage Center

Meteoric rise turned after 1945 into a decline in the number of farmers and their colonies. The Jewish Farmer magazine stopped publication in 1959. The JAS ceased operations in 1965. But this was not the end of Jewish farming in North America. Several hundred families continued to farm and a handful of highly successful Jewish owned agro-businesses continued at least until the end of the 1960s.

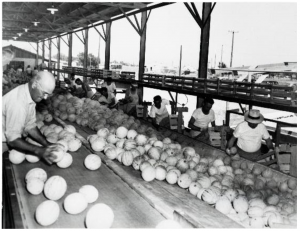

Sam Hamburg (left), born in Russia in the 1890s, at his melon sorting facility, Central Valley, California, circa 1960.

Hamburg was among the most successful and innovative farmers in California at the time and served as an agricultural consultant to the Israeli government.

Credit: Beth Hatefutsoth Photo Archive

Growing Success:

Professionalized Farming, 1910s-1950s

From the Am Olam debacle into the 1910s, the list of unsuccessful colonies rivalled successes. Small, short-lived communities arose and then within years (or even months) disappeared in places like Twelve Corners, Michigan (1891), Endicott, near Baltimore (1903), Arpin in Wood County, Wisconsin (1904), Bay Minett, Alabama (1912), Ida Straus, Montgomery and Liberty Counties, Texas (1912) and Jingo, near Nashville, Tennessee (1916). During these same decades, Jewish workers in New York City tried but failed to sustain small, commutable farms in Fellowship, New Jersey (1912), Farrar, New Jersey (1914), Mohegan, near Peekskill, New York (1915) and Harmonia, near Plainfield, New Jersey (1924).

What helped make the next generation of Jewish farming more successful?

The entrance of a major, well-endowed transnational philanthropic organization into Jewish farming in 1889 made a big difference. Baron Maurice de Hirsch of Paris, one of the wealthiest Jews in Europe, established a branch of his Jewish Colonization Society in New York, naming it the Baron de Hirsch Fund. It offered aid to immigrants, vocational training, English-language instruction, and active support for agricultural colonization. The Fund had immediate impact. For example, by 1899 it had already assisted 600 Jewish immigrant families in New York City become farmers in New England. Among the de Hirsch Fund’s most impactful contributions in the 1890s was establishment of the first Jewish professional farming school in the country, in Woodbine New Jersey.

Click on the image below to view it in greater detail.

Starting around the turn of the 20th century, the de Hirsch Fund, and its partners – the Jewish Agricultural Society and the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society – established new colonies in geographic clusters in southern New Jersey, along the Hudson Valley in New York state, in Connecticut, and elsewhere.

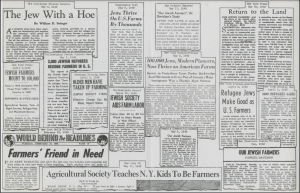

A laudatory report about Jewish farming colonies in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle,

January 6, 1901, page 39.

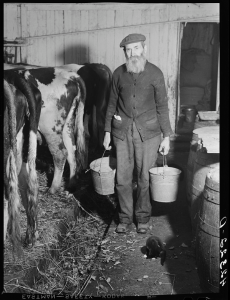

Thanks to its increasing profitability and because soil quality did not impact it, dairy farming became a primary occupation among colonists around the Catskills and in Connecticut starting in the 1910s. For the same reasons, poultry production became a main source of income for many Jewish colonists around the country starting in the 1920s.

As colonists and their philanthropic supporters discovered in many sites of Jewish farming, additional non-farming sources of income had to be found to supplement household economies. In the northeast and mid-Atlantic states, colonists experimented from the mid-1910s with a new industry: boarding and vacation lodgings for urban Jews who could not otherwise afford – and it some cases were not permitted in – existing hotels and resorts in the countryside. This new business on the farms made sense because of their proximity to urban centers (usually within 2-3 hours by train or car) and comfortable summer climates. Why this industry? With no major investments, farmers could offer rural vacation spots that provided fresh, kosher food for Jewish clientele. Within a few years some of these guest houses became quite large, hosting thirty tourists at a time.

The exhibit now explores specific areas in the United States with high densities of Jewish farming. These by no means exhaust the story. Rather, these are illustrative chapters in the much larger book of Jewish agriculture.

In the Catskills: From Farms to the “Borscht Belt”

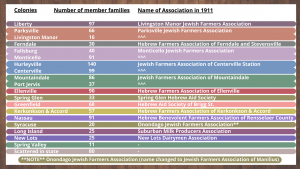

In 1912, the farming population in New York state was approximately 7,000 people, settled mostly in Sullivan and Ulster counties. Of the forty-five Jewish cooperative farm organizations nationwide in 1911, New York State was home to fourteen of them, with a total of 1,004 member families.

In 1911, the Jewish Agricultural Society surveyed them:

Hebrew Congregation of Mountaindale Synagogue,

founded in 1912 by Jewish farmers in the area

Credit: Wikipedia

Like their counterparts in Connecticut and in the Berkshires, rocky soil challenged colonists in New York state. In response, by the early 1900s many of them began supplementing their incomes by offering to city Jews modest getaways on their farms or, alternatively, a site for Jewish summer camps in places like Liberty. These business ventures evolved into what became known as the “Borscht Belt” of resorts in the Catskills. In their heyday during the 1950s-1960s, the “Jewish” Catskills drew 500,000 visitors annually, making the “Borscht Belt” the world’s largest resort area at the time.

Let’s look at some examples of these pioneers:

Asher Selig Grossinger’s family farm in the Ferndale Hamlet of Liberty, Sullivan County was among the first to experiment with Jewish vacationing in the early 1900s. After a few years of hosting individual boarders from the city, Grossinger opened his Catskills Resort Hotel, complete with full service dining and entertainment.

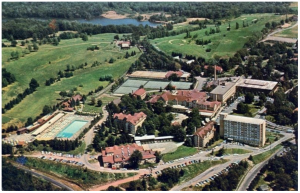

Left: Grossinger’s Catskill Resort Hotel, circa 1960.

Credit: NYup.com

Grossinger’s Catskill Resort Hotel, circa 1960.

Credit: NYup.com

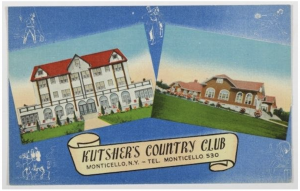

Nearby in Monticello, Max and Louis Kutsher opened their Kutsher’s Brothers Farm House for summer boarders in 1907. Max, his wife Rebecca, and brother Louis immigrated to the United States a few years earlier in search of better lives. Working as tailors on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, they saved enough money to purchase farmland and established their Farm House. Within a couple of decades, Kutsher’s Country Club evolved into one of the preeminent Catskill resorts.

Kutsher’s Brothers Farm House, early 20th century

Credit: http://kutsherstribeca.com

Postcard from Kutsher’s, undated

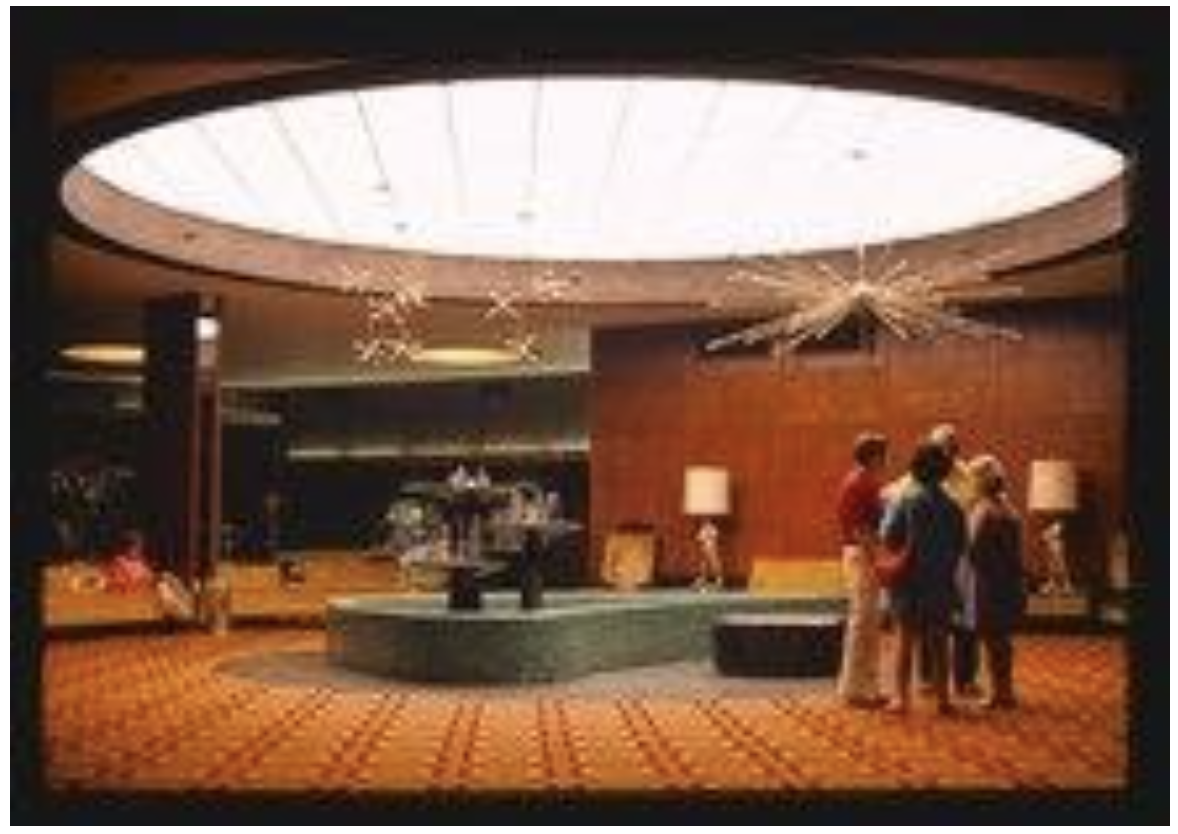

Charles Slutsky opened the Nevele Falls Farm House for summer boarders from the city sometime between 1901-1908 in a barn on his farm in Wawarsing, just outside of Ellenville. That business eventually became one of the giants of the “Borscht Belt,” the Nevele Grande Hotel.

Left: Nevele lobby, 1978

Credit: Wikipedia

This was not the first time Jews had farmed around Wawarsing. In 1837, an affluent Jew, Moses Cohen, bought land in the area and established the short-lived Sholem (or Shalom) colony.

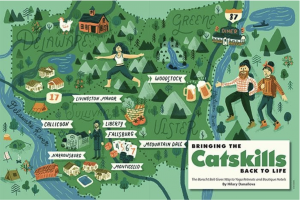

The “Borscht Belt” withered in the 1980s and today is only a memory. But small groups of young Jewish farmers are (re)finding the Catskills. A Hadassah Magazine article from September 2019 titled, “Young Jews Are Bringing the Catskills Back to Life,” featured the whimsical illustration below (Jessica McGuirl/First Pancake Studio).

The illustration above is a nod to this agricultural and resort past, while recognizing how a new generation of farmers in the region are developing their farm-to-table restaurants and small businesses focused on wellness care. In some cases these are situated in the same locations as the original Jewish colonies and “Borscht Belt” institutions that disappeared over time. For more examples of new experiments in Jewish farming, see the “New Generations” page in this exhibit.

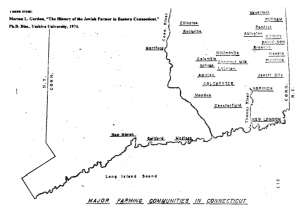

Connecticut

First signs of Jewish agricultural life in the state appeared in 1891, when United Charities of New York City invested resources from the de Hirsch Fund to settle three families in New London and Norwich; all three had worked as dairy farmers in Russia before emigrating. A year later one of them, Haim Pankin, established a farming community of 28 families in Chesterfield with support from an Orthodox congregation in Brooklyn and the de Hirsch Fund, which funded construction of a creamery and synagogue for the colony.

Of the 600 Jewish farming families in New England in 1900, most settled in Connecticut, concentrated in the state’s rural southeast (Chesterfield, Colchester, Montville, Norwich and New London). All of them invested their own money to purchase farms, with mortgages often underwritten by the philanthropic organizations. Daily life for most colonists at the time was spartan, often without electricity, plumbing and paved roads.

Anshei Israel Synagogue in Lisbon/Jewett City, built in 1936. Within a few years of their founding, farming communities in Connecticut usually built at least one synagogue, most of them Orthodox.

Credit: The Baron Hirsch Community

Strains on colonists lightened in the mid-1910s with the help of credit from federal agencies and the Jewish Agricultural Society. Growth came quickly thereafter. By 1916, sixteen farming cooperatives operated in Connecticut, from the relatively large Colchester Jewish Farmers’ Association (147 member families) to the small Rocky Hill Jewish Farmers’ Association (12 member families). That should be no surprise; from 1911 the JAS encouraged colonists to form cooperative credit unions by offering $2 at 2% interest for every $1 the associations collected from members. In fact, the first Jewish farmer’s credit union in the United States formed in Fairfield, Connecticut, in 1911.

Expansion of Jewish farming life in Connecticut from the 1910s also happened as a consequence of general rural depopulation. As veteran non-Jewish landholders left their farms, a need arose for new farmers and made underpriced farmland available. Jewish farming gravitated toward growing tobacco and potatos in the fertile Connecticut River valley but focused on livestock elsewhere in the state when soil conditions were less favorable.

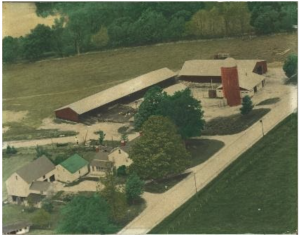

Aerial view of the Loew family farm, located in Hampton, Connecticut, 1960. The Loews came to the United States in the late 1930s as young refugees from Nazi Germany. Their entry was made possible by virtue of agricultural training before emigration, organized by the German-Jewish community at the Gross-Breesen farm in Silesia.

Credit: Courtesy of The Jacqueline E. Jacobsohn Collection

The first son of the colonies enrolled in the Connecticut Agricultural School (later renamed the University of Connecticut) in 1898. For the next half-century Connecticut’s Jewish colonists played an important role in the state’s rural economy and many of their children ascended to positions of authority in its agricultural agencies.

Like in colonies throughout the United States and around the globe, Jewish-owned light industries often were included in farming communities. For example, in Colchester, a number of garment-making businesses employed Jewish colonists. One of those was Levine & Levine Ladies Coat Factory.

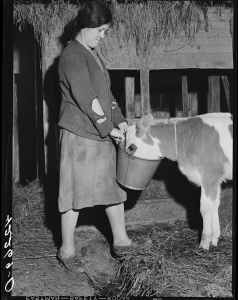

Mary Dralick, a sewing machine operator at Levine & Levine, 1940. Shown on her father’s farm near Colchester. The photographer (Jack Delano) noted, “After a day’s work at the shop she helps with the milking and feeding of the cows.”

Credit: Jack Delano, Library of Congress

Levine & Levine, Colchester, 1940

Credit: Jack Delano, Library of Congress

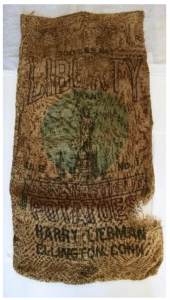

Mark Raider’s 1995 study (“Jewish Immigrant Farmers in the Connecticut River Valley: The Rockville Settlement,” American Jewish Archives 47, no. 2: pp. 213-242) showed how Jewish farming in the north-central part of the state expanded. In 1897 a family of immigrants from Russia – the Rosenbergs – purchased farmland here. Several families followed them, buying farms from aging owners. The cost of such farms ranged from $1,000-$10,000. The Rosenbergs and other Jewish farmers in the area founded a mutual aid society in 1905, which in 1907 became the Connecticut Jewish Farmers’ Association of Ellington. By 1909 the Association included 72 members, aided by technical support and loans from the JAS. Two years later the Association opened a cooperative bank.

A potato sack from the packing house of Harold Liebman in Ellington. Liebman’s farm was located in Lebanon, approximately 25 miles south of Ellington.

Credit: Connecticut Jewish Historical Society

Growing prosperity in Rockville-Ellington allowed congregants to build a synagogue, Knesset Israel, opened in 1913.

Left: Knesset Israel Synagogue in Ellington.

Credit: Wikipedia

In response to shifting commercial trends, farmers in the area swung toward egg production in the late 1920s, forming the Central Connecticut Cooperative Farmer’s Association to buy, mix and sell poultry feed; 90 percent of the Coop’s members were Jews in 1953.

Abraham Lapping, Jewish poultry and dairy farmer

Colchester, Connecticut, undated

Credit: Library of Congress

Click here to see a documentary film titled “Harvesting Stones: Jewish Farmers of Eastern Connecticut.” The film tells the story of Jewish farmers in Connecticut, with special attention to refugees from Nazi Germany during the late 1930s and Holocaust survivors after 1945. As in New Jersey, in Connecticut the Jewish Agricultural Society and other communal organizations resettled hundreds of Holocaust survivors in existing Jewish farming communities. These new farmers helped the colonies survive for at least another decade after 1945.

A Jewish farming family in Chesterfield, as seen in “Harvesting Stones”.

Mid-Western & Western United States

Jewish farming in the West began with Am Olam communes. Jacob Schiff, the unofficial leader of American Jewry around the turn of the 20th century was among the most enthusiastic promoters of Jewish agricultural settlement beyond the Mississippi River. Even when the dust had barely settled from the collapse of the Am Olam movement in the mid-1880s, and evidently without much thought about the fate of the indigenous populations in nearby reservations, attempts abounded to settle Jews on the land on the American frontier.

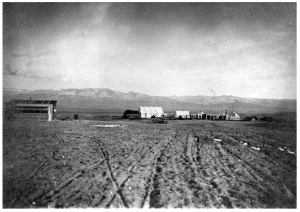

An unlikely spot for a colony in this early generation was in Sanpete County Utah, where the Clarion colony began in 1911. Settled by East European Jewish immigrant families who arrived first in New York and Philadelphia, Clarion had 200 members by 1912. Led by a student trained at the Jewish Farm School in Doylestown, Pennsylvania (Benjamin Brown, formerly Lipshitz), the Clarion colonists planted wheat, alfalfa and oats on 1,500 acres of the 6,000 unfertile acres that had been purchased for the colony by the Mormon church.

First structures in Clarion, circa 1911-1912, photographer unknown.

Credit: Jewish Museum of the American West

Sadly, Clarion’s first two crops failed due to drought, flooding and an early frost, dooming the colony early on. Some families remained in Utah after Clarion’s dissolution in 1915 and created long-lasting agricultural cooperatives that stayed active even after the last Jewish farmers left the area in the 1920s; others returned immediately to the East Coast in 1915.

Benjamin Brown went on in the 1930s to create Provisional Commission for Jewish Farm Settlements in the United States, which established what became the Roosevelt Colony in New Jersey.

Agricultural resettlement in the Midwest continued into the next decades. In one colorful example, in 1933 a group of radical anarchists, led by an immigrant from Russia and newspaper editor named Joseph J. Cohen, founded the Sunrise Cooperative Farm Community in Alicia, near Saginaw, Michigan. A rigidly collectivist farm, Sunrise Commune reached a total membership of more than 90 families (300 individuals) with 9,000 acres of farmland.

On June 28, 1935 the Detroit Jewish Chronicle published this article on the Sunrise Commune.

To see the article in greater detail, click here

Internal ideological struggles quickly fragmented the commune. By 1938, most of its members had left; some of them reconstituted Sunrise in Virginia, where it survived another two years before dissolving again.

Credit: Jessica Drossin

Petaluma

A fascinating chapter in Jewish farming history in the West comes from Petaluma, Sonoma County, not far from San Francisco. Petaluma was one of more than a dozen Jewish farming communities in California founded in the first half of the 20th century. In Petaluma, a first Jewish immigrant, Sam Melnick from Lithuania, purchased a few acres of farmland in 1904. Having heard of Melnick’s success in poultry farming, and also drawn to the moderate climate in northern California, more families followed. By 1921, 65 families owned farms in the area. Jewish and non-Jewish farmers alike in Petaluma weathered ups and downs in the poultry market. The Jewish farmers quickly formed self-help organizations to support newcomers, who also benefited from generous credit from the local Haas family and the Hebrew Free Loan Society of San Francisco.

A celebration in August 1925 for the opening of the Petaluma Jewish Community Center. Many of the participants were poultry farmers in the area.

Credit: The Jewish News of Northern California, October 24, 2014.

At the end of the Second World War boom years, Petaluma was home to 175 families and then absorbed another 50 families of Displaced Persons during the postwar years, bringing the community to a total of 300 families in the mid-1950s. In these years Petaluma was home to the highest concentration of Jewish farmers west of the Delaware River.

Benjamin B. Sovel next to a poultry truck, Redwood Highway, Petaluma, 1931

Credit: Sonoma County Library

But like many poultry-producing communities, the Jewish population of Petaluma declined rapidly starting in the late 1950s due to the burgeoning frozen poultry industry in North America.

Left: A book stamp from the Petaluma Jewish community

Credit: Yiddish Book Center

In this photo from 1924, we see a colonist, Basha Singerman, collecting eggs on a local Jewish farm. Born in Minsk, Singerman arrived in Petaluma in 1915 via a short stay on Jewish dairy ranch near Nairobi, Kenya.

Credit: Zelda Bronstein and Kenneth Kann, “Basha Singerman, Petaluma Comrade,” California Historical Quarterly, Vol. 56, No. 1 (1977): p. 10.

Political drama intruded on Jewish life in Petaluma. Its founders were highly politicized immigrants from Eastern Europe, including Yiddishists, socialists and Zionists. These groups lived in separation but congenially, each one promoting its own ideology and cultural activities. Things changed during the McCarthy era, when enduring animosity emerging between them.

Kenneth Kann, in his book Comrades and Chicken Ranchers (page 79), quotes a non-Jewish neighbor commenting on Jewish farmers in Petaluma, including the interplay between deep social solidarity and internal political divisions:

Petaluma Coop Hatchery, 1954

Credit: Sonoma County Library

Click below to view a documentary film about the founding of the Petaluma colony and the lives of its Jewish farmers

…

Prewar and Post-Holocaust Resettlement of European Jews

Did resettlement of European refugees in North American colonies really matter from the mid-1930s until the mid-1950s? Unquestionably, yes. We must remember that restrictive immigration laws in the United States and Canada meant that most Jews could not enter after 1924. One crucial exception was trained farmers. For example, Jewish cattlemen from rural Germany purchased and refurbished abandoned livestock farms near Binghamton and Albany, New York with help from the Jewish Agricultural Society. According to the JAS, in 1937 eleven refugee families from Germany applied for farm loans. The next year applications rose to 600, and increased again to 741 in 1940.

In another case, after the rise of Hitler the German-Jewish community established training farms for young people specifically as a means to secure them entrance visas to Palestine, western Europe and the Americas. One of these training farms was located next to a small village in Silesia, Gross-Breesen, which saved a total of 130 young German Jews. A large group of them emigrated to Hyde Farmlands in Virginia, thereafter dispersing in the United States, some of them to farms.

Left: Young men recently arrived from Gross-Breesen shucking corn at Hyde Farmlands

Credit: Courtesy of The Jacqueline E. Jacobsohn Collection

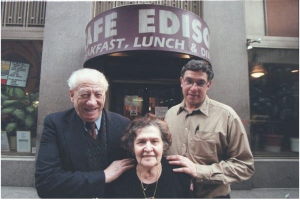

After the Holocaust, the Jewish Agricultural Society resettled 2500 Displaced Persons. Among them were Frances (Frima) and Harry Edelstein. Holocaust survivors from Poland, the Edelsteins emigrated in 1947 and settled on a poultry farm in Dorothy, a Jewish colony in New Jersey. From there they moved to Brooklyn, where they ran coffee and candy shops. Eventually the Edelsteins became owners of Café Edison, an iconic Broadway eatery, otherwise known as “the Polish Tea Room.”

Frances and Harry Edelstein, and their son-in-law, 2001.

Credit: New York Times, Sept 25, 2018.

An important factor encouraging arrival of DPs in the colonies: the 1948 Displaced Persons Act stipulated that farmers were a priority immigration category and received one-third of the entrance visas to the United States. New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, and California proved the most attractive regions to resettle DPs as farmers.

You can find oral history interviews from Jewish farms in the United States on the website of the

Yiddish Book Center