Despite pressures of modernization, anti-Jewish prejudices and shifting conceptions about the virtue of farming, East European Jews never entirely abandoned it. For example, individual Jews in the Polish lands leased, managed and even owned farmlands until the Second World War. Although in hindsight it might seem a very improbable location, Imperial Russia was the starting gate for modern organized Jewish farming. After all, collective memories among Jews usually emphasize histories of oppression throughout the Diaspora. According to these narratives, the autocratic Russian Empire and the Soviet Union in its wake were constant repressors of Jews.

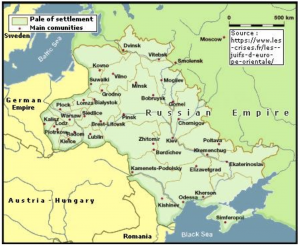

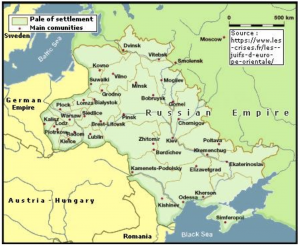

Central to this image of a repressive Russia was the “Pale of Settlement” that physically confined the Jews of the Russian Empire to a handful of western provinces, where they suffered from poverty and political repression.

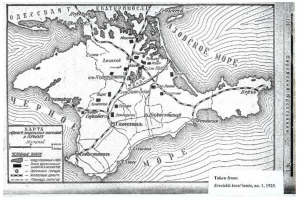

Jewish Pale of Settlement in the Russian Empire. From 1807 to 1917 the Pale demarked the only area where Jews could legally reside in the Empire, with few exceptions. This changed only after the February 1917 Revolution that overthrew the Russian autocracy.

Whatever the historical accuracy of these beliefs about Russia, its tsars initiated organized Jewish agricultural settlement in the modern period and Soviet Russia did much to expand it exponentially.

How did such an unlikely thing happen?

In 1804 Tsar Alexander I issued a “Jewish Statute,” which created the first legal framework in the world to facilitate a large-scale Jewish farming project.

Portrait of Tsar Alexander I of Russia, ruled 1801-1825, by Franz Krüger

Why did a Russian Tsar support Jewish agrarianization in his empire?

Alexander I, known for liberalism in his first years of rule, issued the Statute in response to deadly anti-Jewish pogroms that had erupted a few years earlier in modern-day Belarus. Overall, the Statute intended to deter future pogroms. Russia’s rulers did not value Jews but they did fear how pogroms unleashed uncontrolled violence in the Empire. Among the Statute’s many clauses, it offered an unlimited number of Jews large tracts for agricultural colonization in “New” Russia (located in today’s southern Ukraine and Crimea). If successful, Jews resettling to these rural regions from the Pale would serve two inter-connected goals: populating the recently conquered “New” Russia with white Europeans and, simultaneously, getting Jews out of the volatility raging in the Pale of Settlement.

How did the Jewish Statute of 1804 promote agricultural settlement?

The answer to this question is embodied in these annotated excerpts from the section in the Statute titled “Rights of Farmers.”

-

Jewish farmers are freemen and may not, under any circumstances, be enslaved [enserfed] and cannot be given as property.” Jewish farmers, unlike the vast majority of Russian Orthodox peasants in the Russian Empire until 1861, could not be enserfed.

-

“Jewish farmers as well as manufacturers, artisans, merchants and burghers can buy unpopulated land, sell it, give it as a gift or by inheritance, make mortgages and inherit it in the [Pale of Settlement] gubernias of Lithuania, Belarus, Malorossia [Eastern Ukraine], Kiev, Minsk, Volynsk, Podolsk, Astrakhan, Kavkaz, Yekaterinoslav, Kherson and Tavrida…” This clause gave Jews land ownership rights in the Pale of Settlement, at least in principle. Subsequent decrees would limit these rights.

-

“If they have the right to buy land, Jews can farm it using hired or contract workers.” Employment of hired laborers allowed Jews, in principle, to make their farms profitable.

-

“Those Jews who have no possibility of buying their own land or renting land from landlords, can relocate to crown lands in gubernias: Lithuania, Minsk, Volynsk, Podolsk, Astrakhan, Kavkaz, Yekaterinoslav, Kherson and Tavrida. In some of these gubernias up to 30,000 desyatins [about 81,000 acres] of land could be set apart for the first time [land owner].” Perhaps the most important part of the farming-related items in the Statute, this clause allowed Jews to acquire from the state large tracts of farmland to form farming colonies.

-

“No Jews will be forced to relocate, but those who do so, will be freed from any taxation for 10 years, besides local tax and will receive a loan for settlement that they have to repay based on the same rules as apply to similar loans for foreign colonists.” This meant that the Russian state would invest resources in Jewish farming colonization.

Portrait of Gavril Romanovich Derzhavin, Russian poet and statesman

Painted by Vladimir Borovikovsky, 1795

Alexander I’s “Jewish Statute” resulted from an official investigation headed by Derzhavin.

Did this tsarist-era project succeed in bringing Russian Jews to the land?

Inspired by the promise of freedom and a safe new life, thousands of Jews from the Pale began migrating in 1806 to southern Ukraine and established colonies there, many with Hebrew names like “Sde Menucha” (Field of Rest) and “Nahar Tov” (The Good River). In the 1830s and 1840s, Tsar Nicholas I expanded areas allotted for Jewish colonization further east in Ukraine and also opened Bessarabia – at the time an imperial province – for Jewish agricultural resettlement.

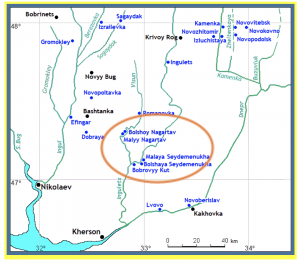

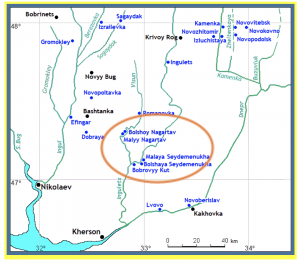

In red: the approximate territory permitted by Tsar Alexander I for Jewish agricultural colonization in the Russian Empire under the 1804 Statute and extended by Tsar Nicholas I in the 1830s-1840s.

In yellow: the approximate territory permitted by Nicholas I for Jewish agricultural settlement in Bessarabia

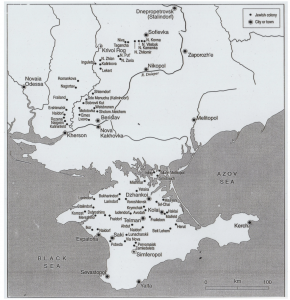

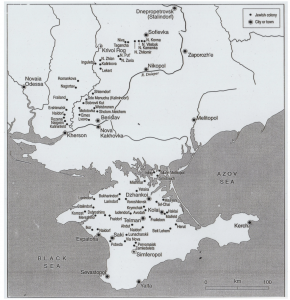

Map of the settlement region in southern Ukraine resulting from the 1804 Jewish Statute. Colonies created before the First World War are marked in blue. Five of the first colonies are circled: Bolshaya Seydemenukha (Large Sde Menucha), Malaya Seydemenukha (Small Sde Menucha), Bobrovy Kut’, Small Nahar Tov and Large Nahar Tov (spelled as the russified “Nagartov”). All of the colonies were situated along rivers, the primary form of transportation and commerce in Russia until the 20th century.

Credit: Yaakov Pasik

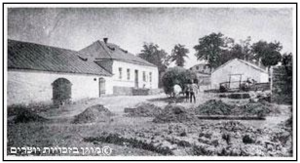

Conditions during migration from the Pale of Settlement to the colonies and in their first decades on the land were very tough, mostly due to government neglect and lack of infrastructures. Many colonists suffered greatly and large numbers abandoned the land. Conditions in the colonies improved very slowly as support from the Russian state arrived. Improvement quickened considerably in the 1890s, when Baron de Hirsch’s Jewish Colonization Society began to assist the colonies. By the First World War, these were relatively prosperous centers of multi-generational Jewish rural life, home to nearly 40,000 colonists in 36 colonies. Their experiences, good and bad, also modeled what might be possible for Jewish farmers in other parts of the world.

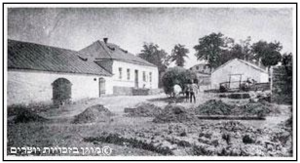

Colonists and buildings in Sde Menucha, 1910s-1920s

Credit: National Library of Israel

Here is a documentary released in 2016 by Boris Shusterman (in Russian & Ukrainian). It offers a history of Bobrovii Kut, today a rural village in southern Ukraine. But Bobrovii Kut’s history began with settlement by Jews from Belorussia and northern Ukraine during the first wave of agricultural colonization to the region under Alexander I’s Jewish Statute. The film features interviews shot on location with village elders. Like nearly all of the Jewish colonists in southern Ukraine, Nazi armies and their local collaborators murdered Bobrovii Kut’s colonists in September 1941.

Under the Bolshevik Regime: 1918 – 1941

The Bolshevik Revolution in October 1917 rattled the political landscape in Eastern Europe. The resulting Civil War and Russo-Polish War from 1918-1921, following closely on the heels of the First World War, brought catastrophe to Russia’s Jews and the Jewish colonies founded in the 19th century. Amid hopelessness in what had formerly been known as the Pale of Settlement and with communal memories still alive about the prewar agricultural colonies, small groups of young Jews began a spontaneous movement “to the land” in 1922, in Soviet Ukraine and Crimea as well as to the older colonies.

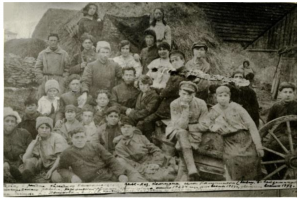

Colonists in Sde Menucha Ketanah, Ukraine, 1923

Credit: AJJDC Archives

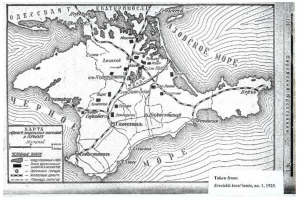

Soviet Crimea in 1925.

The location of the “spontaneous” Jewish colonies and communes settled between 1922-1924 are marked in black squares, before the arrival of the western philanthropic agencies, like the Agro-Joint. Most of these colonies with Russian names like Pobeda (Victory) and Rabotnik (Laborer) were founded by Jews hoping to create new lives in the Soviet Union, far from the trauma they left in the Pale of Settlement. A handful of these “spontaneous” settlements took Hebrew names like Beit Leḥem and Aḥdut (Unity). Three of them (Tel Ḥai, Mishmar and Ma’ayan) were Zionist training communities, founded to prepare future immigrants to Palestine for farming life.

Spontaneous resettlement of Zionists and non-Zionists from the former Pale to the Black Sea littoral grew exponentially starting in 1924, when foreign philanthropic organizations and the Bolshevik regime signed a series of contracts for mass land settlement. Both saw agricultural colonization as the best chance of rebuilding the lives of hundreds of thousands of impoverished, traumatized Soviet Jews who could not leave the USSR because of restrictive immigration laws in the West.

An illustration from an official Soviet publication showing the numerical growth of Jewish farmers from 1913 to 1927.

Between the world wars hundreds of new state-of-the-art agricultural colonies came into being, alongside reconstituted colonies from the 19th century, all orchestrated and supported by the Agro-Joint (the operative arm of the Joint Distribution Committee in Soviet Russia), the ORT and the JCA.

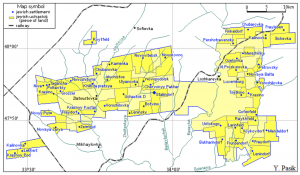

A partial illustration of Jewish agricultural colonies (renamed kolkhozes) in interwar Soviet Crimea and southern Ukraine. In total, by 1941 approximately 200 Jewish farming communities dotted this massive region of the USSR.

Credit: Jonathan Dekel-Chen, Farming the Red Land.

From 1923-1941, approximately 200,000 Jews resettled from devastated towns in the former Pale of Settlement to these farming colonies and thereby restarted their lives.

Novyi mir (New World) colony, Odessa region, 1927

This colony was established in 1924. Within three years the colonists were living in well-built private homes instead of barracks or dugouts.

Credit: World ORT Photo Archive

Family home and barns, Fraiheym (Free Life) colony, Odessa region, 1927

Credit: World ORT Photo Archive

The meteoric growth of Jewish colonization, combined with a new Soviet nationalities policy, brought the Kremlin to establish five Jewish Autonomous Districts between 1927-1935.

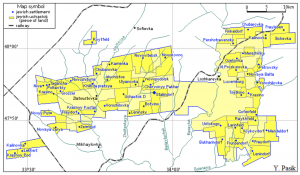

These five districts – Fraidorf and Larindorf in northern Crimea, Kalinindorf, Stalindorf and Novo Zlatopol’ in southern Ukraine – administered daily life in the Jewish colonies and for their non-Jewish neighbors, with Yiddish as a recognized official language and Yiddish-speaking governmental institutions.

Stalindorf Jewish Autonomous District, located just east of Krivoy Rog, Ukraine. Part of the Ekaterinoslav region under the Russian Empire, Soviet authorities later renamed Stalindorf as Izluchiste and merged the district into the Dniepropetrovsk province. Note the railway lines intersecting the region. The railroad became a main means of transportation in much of the Russian Empire in the early 20th century.

Credit: Yaakov Pasik http://evkol.ucoz.com/stalindorf_en.htm

Most of the colonies formed during the interwar period were organized around cooperative associations. That high frequency of production and marketing cooperatives helps explain why Jewish colonists in the USSR suffered relatively little from Joseph Stalin’s forced collectivization of Soviet agriculture in the winter of 1929-1930. In the simplest of terms, Jewish colonies did not need to undergo the shock of forced collectivization because they were functional cooperatives from the start. Also, the philanthropic organizations – led by the Joint Distribution Committee’s operative arm, the Agro-Joint – had implanted mixed farming economies in the colonies, with each growing many crops, livestock and varieties of vineyards or orchards.

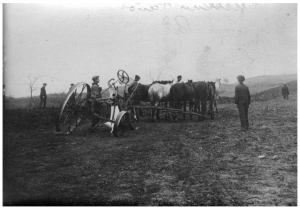

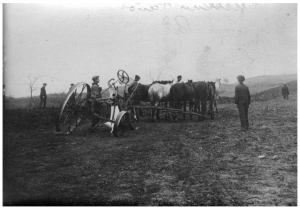

Colonists at field demonstration at a Jewish Agricultural School, Odessa region, Ukraine, 1924. Multiple agricultural schools created by Agro-Joint and the JCA, as well as intensive, high-quality professional instruction in the regions of colonization meant that the colonists enjoyed received advanced farming skills.

Colonists at field demonstration at a Jewish Agricultural School, Odessa region, Ukraine, 1924. Multiple agricultural schools created by Agro-Joint and the JCA, as well as intensive, high-quality professional instruction in the regions of colonization meant that the colonists enjoyed received advanced farming skills.

Credit: World ORT Photo Archive

In addition, the support organizations introduced modern agricultural mechanization, drilled deep wells, built modern irrigation systems and farm-related industries like dairies. These all made the colonies self-sustaining, relatively immune from the regime’s forced requisitions of grain and valuable to the Kremlin as living examples of what could be accomplished by the nation’s primitive agricultural economy through modernization.

As a result, while the forced Soviet agricultural policy of “Total Collectivization” during the tragic winter of 1929-1930 wrought rural devastation and the death of millions from famine in the early 1930s, Jewish colonies survived relatively unharmed. One of the few visible effects was a requirement to rename colonies as kolkhozes (Russian for “collective farms”). Most colonies with Hebrew names had to change them to Russian. So Sde Menucha became the Kalinindorf kolkhoz and Tel Ḥai became the Oktiabr kolkhoz. Also, the Stalinist terror that accompanied Total Collectivization almost entirely bypassed Jewish colonists.

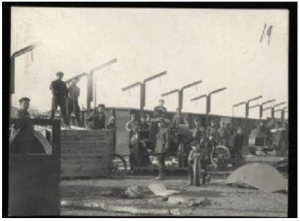

Agro-Joint workers unpack John Deere tractors imported from the USA for the Jewish colonies, often shared with their non-Jewish neighbors

Dzankoi, Crimea, 1930s

Credit: JDC Photograph Archive

Another pivotal, tragic moment in Soviet history – Stalin’s horrific purges in the second half of the 1930s – almost entirely bypassed the colonies, except for rare cases. A different fate, however, awaited the western philanthropic support organizations and their staffs. By 1938 the Kremlin pushed out all foreign service organizations from the USSR. Dozens of local employees of agencies like Agro-Joint and the JCA, unable to flee the USSR, were swept up in the murderous whirlwind of Stalin’s dictatorship. Many of them did not survive.

Staff of the Agro-Joint in its main office in Moscow, late 1920s. Joseph Rosen is seated third from the right.

Most of employees were arrested and imprisoned during the purges. The highest-ranking among them were executed or perished in Soviet GULAGs.

Credit: AJJDC Archives

One of the greatest surprises of this chapter in modern Jewish agricultural life is that the 200 kolkhozes continued to thrive after the departure of the foreign philanthropies and the disappearance of many agricultural professions. The available documents suggest, in fact, that these farms had their highest yields ever from 1939-1940. Murderous Nazi conquerers ended Jewish farming life in the Soviet Union, nothing else.

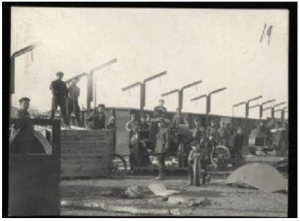

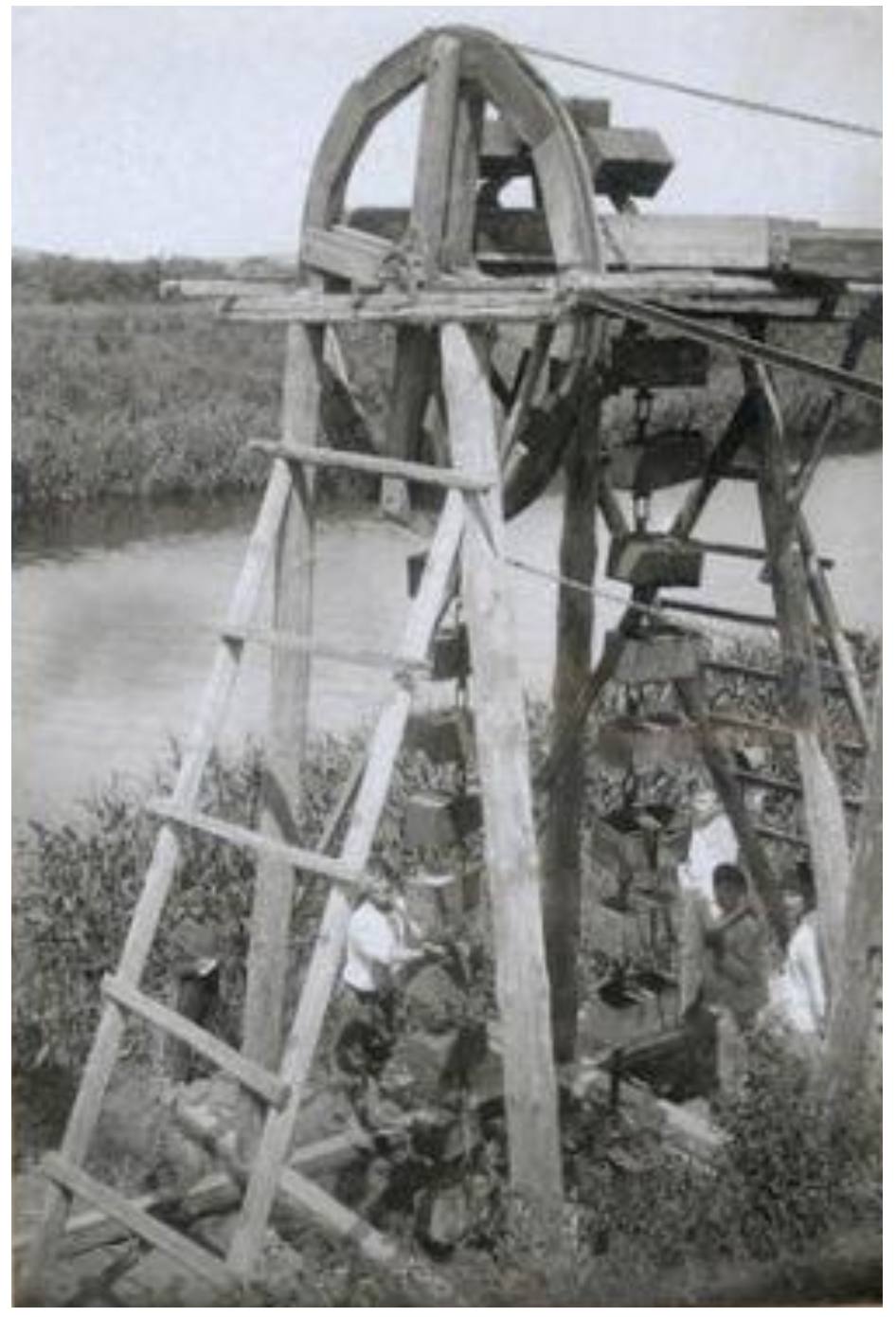

Constructing a waterwheel on the Ingulets River, which fed the colony’s irrigation system, 1936. The Ingulets colony (later renamed a kolkhoz) was among the first Jewish agricultural colonies settled under Tsar Alexander I’s 1804 Jewish Statute.

Credit: Evelyn Morrissey, Jewish Workers and Farmers in the Crimea and Ukraine, New York, 1937

A modern poultry farm, Pervomaisk kolkhoz, Crimea, 1936

Credit: Evelyn Morrissey, Jewish Workers and Farmers in the Crimea and Ukraine, New York, 1937

For further information on Jewish agricultural settlement in Crimea and southern Ukraine, see the Russian-English website created by Yaakov Pasik by clicking here.

Birobidzhan

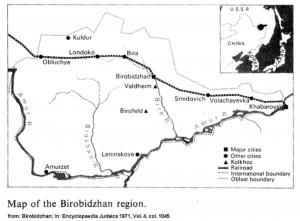

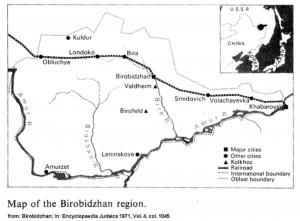

The best-known, and perhaps least understood, Jewish agrarianization project arose in Birobidzhan, located in the Soviet Far East on the border with Manchuria. Concerned about the increasing popularity of Zionism among Soviet Jews and seeking a way to populate this tense borderland with loyal citizens, in 1934 the Kremlin declared Birobidzhan a Yiddish-speaking Jewish National Region, to be built on new industrial cities and Jewish kolkhozes.

The Kremlin’s hoped-for popular alternative to Zionism came to little. From the early 1930s until the Soviet regime purged the Jewish leadership of Birobidzhan in the late 1940s, approximately 40,000 Jews lived there for some time, with most departing shortly after arrival in this harsh, isolated region. Its two Jewish kolkhozes, Waldheim/Valdheim and Birofeld, had brief lifespans; most of their members left within a few years. A key explanation for the failure of these kolkhozes: Jewish philanthropists refused to support what they considered an unsustainable project. Birobidzhan’s towns fared better but never attracted large numbers of Jews. Between the late 1940s and the 1990s, the Jewish population of Birobidzhan hovered around 16,000, with almost all of them emigrating to Israel after the disintegration of the Soviet Union.

An entrance to the city of Birobidzhan today. The monumental sign still features Yiddish, as do many public buildings in the city.

What Birobidzhan lacked in viability as a Jewish homeland it made up for in propaganda value. Soviet agencies disseminated idealized materials at home and abroad of what appeared to be the heroic success of Jewish farmers and industrial laborers made possible by progressive policies from the Kremlin.

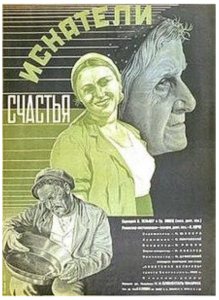

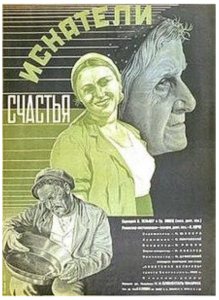

Publicity poster for the film “Seekers of Happiness”

For example, the iconic Soviet film, “Seekers of Happiness”, immortalized Birobidzhan’s triumphant narrative of Russian Jews “from abroad” journeying to Birobidzhan to settle on the fictitious “Red Fields” kolkhoz.

…

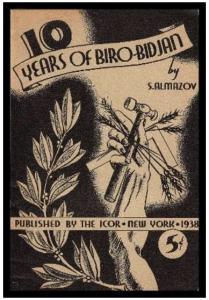

A celebratory pamphlet published in 1938 by ICOR, an agency of the Communist Party in the Americas. The 10th anniversary refers to 1928, when the Kremlin first formed Birobidzhan as an administrative area.

The full pamphlet is available here

Click the images below to view them in greater detail

Cover and page from the Biro-bidjan Pictorial,

published in 1937 in the United States by ICOR

Bessarabia

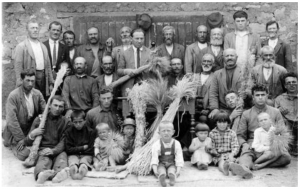

The rich rural history of Bessarabian Jews is mostly forgotten today. Known over the centuries by many different territorial names, this region was part of the Russian Empire in the nineteenth century. Starting in the 1840s, Russia’s rulers allowed the Jews of Bessarabia to form agricultural colonies. Because they learned from hardships experienced by Jewish colonists in southern Ukraine during the first half of the 19th century, the several thousand colonists in Bessarabia fared better and reached a degree of stability more quickly, particularly after the Jewish Colonization Society and the Organization for Rehabilitation and Training (ORT) began supporting them in the late 1800s.

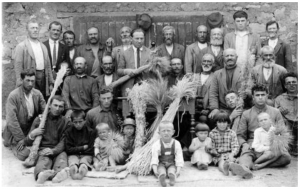

Jewish farmers in the Manzyr Colony, Bessarabia, 1928

Credit: World ORT Archive

Despite great suffering during the First World War and around the region’s transfer to Romania after the war, Jewish colonies in Bessarabia thrived and expanded thereafter, even during a brief period of Soviet rule following the Molotov-Ribbentrop Treaty in 1939. Like most other sites of Jewish life in Eastern Europe, Nazi occupation brought death to the colonies.

ORT agronomist on a visit to Manzyr Colony, 1930s

Credit: World ORT Archive

The interwar Soviet regime also intermittently promoted smaller-scale Jewish colonization projects in Belorussia, Dagestan and Uzbekistan to relieve poverty for local Jews and also to promote productive professions among some of the more traditional Jewish communities. These projects received sporadic support from support agencies like the Agro-Joint.