Just like manuscript cookbooks, historical cookbooks are also a fabulous way to get a glimpse into the past. I always say that there is so much history to be learned though food, and paging through historical cookbooks is a fun (and appetizing!) way to do this. Our Rutgers library collection features both online and actual cookbooks going back to the 1500s! And Google Books has a great repository of historical cookbooks, with scanned texts from the 1600s and beyond.

Historical cookbooks have helped me immensely in my food history research, particularly shaping how a recipe has evolved over time. I do quite a bit of reconstructing older recipes which requires tweaking ingredients and measurements, as many are now different today. This sometimes lengthy process is prefaced with the realization that the final result may not be what was expected.

For example, when I was writing about nineteenth century cooking instructor Mrs. Goodfellow (who had been said to be the inventor of lemon meringue pie), I wanted to see if I could determine exactly when this recipe began showing up in cookbooks. I knew the pie had evolved from one of Mrs. Goodfellow’s signature confections, a rich lemon pudding. Her original recipe calls for the custardy pudding to be either spooned into a pastry crust before baking (like a pie), or simply poured into a dish and baked without a bottom shell. At some point she cleverly thought to top her famous pudding with fluffy meringue.

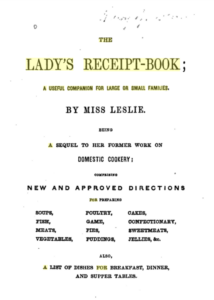

But when did this happen? Although Mrs. Goodfellow never wrote a cookbook herself, throughout the mid-nineteenth century, Eliza Leslie (who had studied under Mrs. Goodfellow’s tutelage) began familiarizing Americans with the concept of meringue-topped puddings via her recipes. In her 1847 cookbook, The Lady’s Receipt-Book: A Useful Companion for Large or Small Families, she says: “Any very nice baked pudding will be improved by covering the surface with a meringue.” And since Miss Leslie wrote down everything she learned at Mrs. Goodfellow’s in a little notebook (and later published it as a series of cookbooks), it can be inferred that topping the lemon pudding with meringue was a method Miss Leslie learned from her classes at Mrs. Goodfellow’s.

But when did this happen? Although Mrs. Goodfellow never wrote a cookbook herself, throughout the mid-nineteenth century, Eliza Leslie (who had studied under Mrs. Goodfellow’s tutelage) began familiarizing Americans with the concept of meringue-topped puddings via her recipes. In her 1847 cookbook, The Lady’s Receipt-Book: A Useful Companion for Large or Small Families, she says: “Any very nice baked pudding will be improved by covering the surface with a meringue.” And since Miss Leslie wrote down everything she learned at Mrs. Goodfellow’s in a little notebook (and later published it as a series of cookbooks), it can be inferred that topping the lemon pudding with meringue was a method Miss Leslie learned from her classes at Mrs. Goodfellow’s.

By the 1860s, lemon meringue pie recipes began popping up in cookbooks nationwide, including Common Sense in  The Household – A Manual of Practical Housewifery by Marion Harland and The Godey’s Lady’s Book Receipts and Household Hints by Sarah Annie Frost. Although sometimes called iced lemon pie, lemon cream pie, or lemon custard pie, they all featured a meringue topping. In fact, lemon custard pie was a favorite of Abraham Lincoln.

The Household – A Manual of Practical Housewifery by Marion Harland and The Godey’s Lady’s Book Receipts and Household Hints by Sarah Annie Frost. Although sometimes called iced lemon pie, lemon cream pie, or lemon custard pie, they all featured a meringue topping. In fact, lemon custard pie was a favorite of Abraham Lincoln.

You can also see touchstones to specific timeframes when ingredients were scarce or rationed for one reason or another through historical cookbooks. War-time cookbooks are a good example, as is the Irish potato famine from 1845 to 1852. The previously mentioned Miss Leslie wrote a whole cookbook based on the New World food cornmeal, The Indian Meal Book, which was published in London in 1846. In this cookbook, Leslie provides recipes that feature cornmeal as a main ingredient, designed to be a nutritious and less expensive substitute for wheat flour during the time of the potato famine. The idea was to educate the Irish and British about the versatility of maize, or Indian corn, as it was called, thus helping them survive the potato crop failure.

You can also see touchstones to specific timeframes when ingredients were scarce or rationed for one reason or another through historical cookbooks. War-time cookbooks are a good example, as is the Irish potato famine from 1845 to 1852. The previously mentioned Miss Leslie wrote a whole cookbook based on the New World food cornmeal, The Indian Meal Book, which was published in London in 1846. In this cookbook, Leslie provides recipes that feature cornmeal as a main ingredient, designed to be a nutritious and less expensive substitute for wheat flour during the time of the potato famine. The idea was to educate the Irish and British about the versatility of maize, or Indian corn, as it was called, thus helping them survive the potato crop failure.

It is also fun to see the many variations of certain recipes featured in a single cookbook and all the interesting names. For instance, browse through any Victorian era cookbook and you will be rewarded with pages and pages of luscious cake recipes. Some names are familiar, such as Sponge Cake, Lemon Cake or Pound Cake, but many are no longer in common use – Election Cake, Queen Cake, Composition Cake, Taylor Cake and Black Cake (also known as plum cake). Several cakes were known by more than one name, such as Lady Cake (also called Silver Cake or White Lady Cake). Sponge cake in particular had many alternative versions – Almond Sponge Cake, Hot Water Sponge Cake, Cream Sponge Cake, even Perfection Sponge Cake, which called for a whopping fourteen eggs.

You can also see industrial progress through the recipes in historical cookbooks. For example, in the early part of the nineteenth century (before chemical leavenings such as baking powder and cream of tartar came on the scene), a sponge cake’s light, airy texture was achieved by beating eggs and sugar for a long time until they were thick, smooth and pale yellow. This “mechanical leavening” whipped air into the eggs to produce a mass of bubbles called a foam, allowing the cake to rise up nice and light due to the expansion of the air bubbles during baking. It was a long and tedious process that sometimes took hours – a task often delegated to servants.

But the Victorian age introduced many kitchen conveniences, including the invention of the rotary eggbeater around 1870 and chemical rising agents such as saleratus (an early form of baking soda), baking soda and baking powder. These newfangled gadgets and ingredients made the cook’s job much easier. Other examples include chocolate processing, powdered gelatin, canned and boxed goods, the ice cream maker and refrigeration. All these advances changed recipe instructions too. You don’t even necessarily need to go so far back in time to get the idea. Many “retro” cookbooks feature recipes indicative of a specific time when certain things were “in style”, such as Jello molds, canned pineapple, spam or Campbells soup.

Some well-known historical cookbooks from the Rutgers library:

- The art of cookery, made plain and easy : which far exceeds any thing of the kind ever yet published (1747) by Hannah Glasse

- The frugal housewife, or Complete woman cook. (1772) By Susannah Carter (The first American printing of this cookbook actually included plates engraved by Paul Revere)

- American cookery: or, The art of dressing viands, fish, poultry and vegetables, and the best modes of making puff-pastes, pies, tarts, puddings, custards and preserves, and all kinds of cakes, from the imperial plumb to plain cake: Adapted to this country (1796) by Amelia Simmons (the first cookbook by an American to be published in the US, and yes this is the actual title – cookbook titles were often much longer then)

- The Virginia housewife : or, Methodical cook (1860) by Mary Randolph (related by blood, marriage, and social ties to Virginia’s most prominent families including being a second cousin to Thomas Jefferson)