[Following up on the previous post, this is part 2 of our Mystery of Collaborative Mysteries – the mystery of several identical mystery book series published recently. It includes a bit of the history of ghostwriting and lots of speculation on the use of generative AI in publishing – all a mystery!]

[Following up on the previous post, this is part 2 of our Mystery of Collaborative Mysteries – the mystery of several identical mystery book series published recently. It includes a bit of the history of ghostwriting and lots of speculation on the use of generative AI in publishing – all a mystery!]

Creative writing collaborations have a long tradition, from co-authorship to initiatives to preserve the bequest of titles, characters, and plots inherited from a successful author, as discussed in a post about writing in style.

Collaborative Mystery Writers

Sharing authorship responsibilities under a single name is not a new concept in the mystery genre either. Just think of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Established in 1941, the title of this crime fiction magazine goes back to a name created in 1928, covering two separate mystery authors under one pseudonym: Frederic Dannay (1905–1982) and Manfred Bennington Lee (1905–1971). The two authors also edited more than thirty anthologies and commissioned other authors to write using the pseudonym Ellery Queen. The fictional character Ellery Queen is himself a mystery writer and amateur detective who assists his police inspector father in solving murder mysteries.

The Nancy Drew mysteries provide another example. Since 1930, generations of young women have grown up reading the adventures of Nancy Drew. A popular young female amateur sleuth, she is the protagonist in several mystery book series, movies, video games, and even a TV show. The Nancy Drew books were actually written by Mildred Benson and several ghostwriters, published under the collective pseudonym Carolyn Keene by the Stratemeyer Syndicate, a publishing company that produced mystery book series for children. Written for decades by multiple generations of authors, the Nancy Drew Mystery Stories series consist of more than 175 novels, still enjoyable today!

Book Packaging

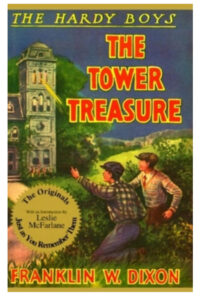

The technique, called “book packaging,” is attributed to a New Jersey author of 1,300 books himself, Edward Stratemeyer, who employed several freelance authors to produce the Hardy Boys series for young boys. These adolescent mysteries became one of the most widely read book series of their time. The Stratemeyer Syndicate, which also published the Nancy Drew series, insisted that the ghostwriters never reveal their authorship of the books.

Leslie McFarlane, the unknown Canadian ghost writer who wrote many of the Hardy Boys stories under the pen name Franklin W. Dixon, announced his role in their creation only a year before his death, with publication of his 1976 autobiography The Ghost of the Hardy Boys. Even his own son didn’t know why these books were on his dad’s bookshelf. Surprisingly, McFarlane, who considered writing the Hardy Boys books as a chore to pay the bills, had no idea how popular they were until visiting the local bookstore. Or so it goes, according to the introduction of the 1991 facsimile edition of The Tower Treasure, written by McFarlane himself.

Leslie McFarlane, the unknown Canadian ghost writer who wrote many of the Hardy Boys stories under the pen name Franklin W. Dixon, announced his role in their creation only a year before his death, with publication of his 1976 autobiography The Ghost of the Hardy Boys. Even his own son didn’t know why these books were on his dad’s bookshelf. Surprisingly, McFarlane, who considered writing the Hardy Boys books as a chore to pay the bills, had no idea how popular they were until visiting the local bookstore. Or so it goes, according to the introduction of the 1991 facsimile edition of The Tower Treasure, written by McFarlane himself.

The syndicate’s strategy of hiring freelancers to write mass-market, standalone books with an identical protagonist from a brief plot or outline while maintaining all copyrights brought financial success to the publisher, but not the ghostwriters. Sharing the workload didn’t come with sharing the fame for the unnamed authors of these books, who were paid a flat fee of about $100 and no royalties.

With the Nancy Drew/Hardy Boys series still going strong today, one can only wonder if, similar to Stratemeyer’s business model, recruiting AI for the publishing industry in this manner will become another way of capitalizing on evolving new technologies. Is that where we are headed in genre fiction now?

What’s that got to do with the price of cheese? Stay tuned for part 3!

Further reading from Rutgers University Libraries

- Books in the Nancy Drew series written under the pen name “Carolyn Keene” in Rutgers Libraries

- Books available from the Hardy Boys Mystery series from HathiTrust

-

Room, Adrian. (2010). Dictionary of pseudonyms : 13,000 assumed names and their origins (5th ed.). McFarland & Co.

- Greenwald, M. S. (2004). The secret of the Hardy boys : Leslie McFarlane and the Stratemeyer Syndicate. Ohio University Press.

- Kismaric, C., & Heiferman, M. (2007). The mysterious case of Nancy Drew & the Hardy Boys. Fireside, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

- McFarlane, L. (1976). Ghost of the Hardy boys: an autobiography. Methuen/Two Continents.

- Rehak, Melanie. (2005). Girl sleuth: Nancy Drew and the women who created her (1st ed.). Harcourt.