A heads-up: This post, like Machado’s memoir, discusses intimate-partner abuse.

There are two distinctive formal features of Carmen Maria Machado’s In The Dream House: A Memoir that are apparent from early on. The first is that this memoir is fractured into a series of short forays, usually just one or two pages, that approach the central story of an abusive lesbian relationship from different angles while relating its course in roughly chronological order. Often these miniature chapters are named after different genres of narrative (“Dream House as Noir,” “Dream House as Stoner Comedy”), as well genres of space (e.g. “Dream House as Inner Sanctum”) and mythic or folklore tropes (“Dream House as Bluebeard,” “Dream House as River Lethe”). The collage of genres highlights how numbingly ubiquitous the abuse of women is to so many of our cultural stories, while also carving out space in the predominantly heterosexual imaginary of domestic violence for the relatively unacknowledged issue of abusive relationships between women. The experimentation with genre also incidentally shows off Machado’s range as a writer, from experimental fiction and polemic essay to those under-respected kinds of writing that provoke a bodily response: suspense, erotica, horror.

There are two distinctive formal features of Carmen Maria Machado’s In The Dream House: A Memoir that are apparent from early on. The first is that this memoir is fractured into a series of short forays, usually just one or two pages, that approach the central story of an abusive lesbian relationship from different angles while relating its course in roughly chronological order. Often these miniature chapters are named after different genres of narrative (“Dream House as Noir,” “Dream House as Stoner Comedy”), as well genres of space (e.g. “Dream House as Inner Sanctum”) and mythic or folklore tropes (“Dream House as Bluebeard,” “Dream House as River Lethe”). The collage of genres highlights how numbingly ubiquitous the abuse of women is to so many of our cultural stories, while also carving out space in the predominantly heterosexual imaginary of domestic violence for the relatively unacknowledged issue of abusive relationships between women. The experimentation with genre also incidentally shows off Machado’s range as a writer, from experimental fiction and polemic essay to those under-respected kinds of writing that provoke a bodily response: suspense, erotica, horror.

The second distinctive feature of In the Dream House is its narrative point of view. Starting from the section on page 14, “Dream House as an Exercise in Point of View,” large stretches of this memoir are told in the second person, narrating the actions and feelings of a past self as “you.” It’s an unusual device: typically we categorize stories as narrated in either the first person (“I”) or the third person (“he/she/it”), and second-person narration seems like a gimmicky outlier, associated with either Oulipian-style experimental constraints (e.g., Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler) or interactive game-fiction (Dungeons and Dragons, or the Choose Your Own Adventure series). Machado plays with both of these genres in parts of In the Dream House, but I’m most interested in what that use of second-person narration says about the genre of the whole: the memoir, particularly the memoir of an abusive relationship.

In any memoir, the person who tells the story is both the same as and different from the person that the story is about. The teller of the tale and the character who experiences it are, in the conventional sense, the same individual––if they weren’t, it wouldn’t be a memoir. But they exist in different moments in time. The narrator speaks from the end of the story, knowing how it will all turn out, while their past self exists within the story. In a technical sense, you could say this about any first-person narrative––that there’s at least a philosophical distinction of levels of narration between the voice that tells the story and the “I” within the story––but it’s most prominent in memoirs or in novels that take the shape of memoirs, where we’re conscious of the narrator existing at a different moment in time from the character in the story who shares their name. For my part, as an eighteenth-century specialist, I think about this as the Robinson Crusoe situation. The Robinson who tells the story is an older Robinson from the one marooned on a desert island, and we’re always aware while reading the narrative that it’s in some sense a story about how the two Robinsons converge, how the imperiled and sinful Robinson escapes from dangers both material and spiritual to become the safe and repentant Robinson who relates the tale at some later date. (A later eighteenth-century mock-autobiography, Tristram Shandy, plays with the idea of a memoir catching up to its memoirist; the narrator promises to keep releasing new volumes until he catches up with himself in the present day, but given that it takes Tristram until Volume III to reach the moment of his birth he seems unlikely to ever run out of material!) By addressing the subject of the memoir as “you,” Machado highlights a distinction common to all memoirs between the self who tells the story and the self within the story.

But calling attention to that split between the self-as-narrator and the self-as-subject is also specific to the subject matter of In the Dream House: an abusive relationship. In “Dream House as an Exercise in Point of View,” Machado describes the separation as a kind of trauma: “You were not always just a You,” she writes. “I was whole––a symbiotic relationship between my best and worst parts––and then, in one sense of the definition, I was cleaved: a neat lop that took first person––that assured, confident woman, the girl detective, the adventurer––away from the second, who was always anxious and vibrating like a too-small breed of dog” (14). The version of herself in the abusive relationship is both recognizably part of her, or her “worst parts,” and cut off, less than “whole.” While it seems at first that the relationship itself is the “neat lop” that separates the “I” from the “you,” the following paragraphs suggest the possibility that this amputation might have been the cost of getting away, like cutting off a limb to escape a trap. “I left, and then lived: moved to the East Coast, wrote a book, moved in with a beautiful woman, got married, bought a rambling Victorian in Philadelphia,” Machado writes, relating the author’s own real-life biography. “But you. You took a job as a standardized-test grader. You drove seven hours to Indiana every other week for a year… I thought you died, but writing this, I’m not sure you did.” It’s as though the version of herself that existed in the relationship, a version that she lopped off and left for dead in the act of leaving, carried on a parallel quasi-life of its own.

Intense relationships, it’s often said, blur the boundaries between “I” and “you.” In an abusive relationship, this blurred boundary becomes weaponized: the abuser effectively takes that ‘shared self’ of the relationship as a hostage. The nature of the threat differs among different kinds of abuse, from emotional to physical, but that kind of hostage-taking is a persistent pattern. In the Dream House figures the attempt to carve out an independent self within an all-consuming and potentially destructive relationship through the humble motif of a doorknob. Machado relates a childhood memory in which she locked her bedroom door after a fight with her parents, only for them to unscrew the doorknob. While grateful her parents were not abusive, she remembers the removal of the doorknob as a “violation of privacy and autonomy,” a “reminder [that] nothing, not even the four walls around my body, was mine” (82). Years later, when her abusive girlfriend is chasing her around the house, she locks herself into the bathroom: “I remember sitting with my back against the wall, pleading with the universe that she wouldn’t have the tools or know-how to take the doorknob out of the door. Her technical incompetence was my luck, and my luck was that I could sit there, watching the door test its hinges with every blow. I could sit there on the floor and cry and say anything I liked because in that moment it was my own little space” (141). It’s telling that this is one of the sections told in the first person as opposed to the second; at a low point in the abusive relationship, the trusty doorknob of that bathroom provides the possibility of an “I” outside of that relationship, an “I” that could choose to keep someone out as well as let them in, an “I” that can be preserved once the “you” of that relationship-self has been left behind.

That image of needing to hide in a dark room of the self has sinister overtones in a queer context, however: the closet. For Machado, a same-sex abusive relationship in a frequently homophobic world heightens that dynamic of emotional blackmail common to abusive relationships in general, the sense of one’s identity being so inextricably bound up with the relationship that it becomes hard to leave even as it’s painful to stay. When the right to have a same-sex relationship at all is contested––in other words, when the “us against the world” dynamic common to many volatile relationships holds a bitter kernel of political truth––it becomes all too easy, Machado suggests, to stay with an abusive partner out of fear that leaving would mean betraying the cause, betraying one’s own queerness. In other words, one of the hidden cruelties of homophobia is the way that it amplifies the fear of leaving an abusive relationship with the fear that doing so would mean returning to the closet, or somehow letting the homophobes win. Machado’s “you” imagines voicing that fear to a sympathetic TSA agent as she breaks down in tears just after leaving: explaining to her how “if your family found out they’d probably think it proved every idea they’ve every had about lesbians, and you wish she was a man because then at least it could reinforce ideas people had about men, and how she probably wouldn’t understand but the last thing queer women need is bad [expletive deleted] PR, and then you feel bad because for all you know this airline employee could be queer, she could understand” (131-1). As another section soon after suggests, the hurt of the abuse is amplified by that sense of a hostile world as well: when someone who shared a persecuted identity with you turns around to persecute you too, “you aren’t just mad, or heartbroken: you grieve from the betrayal” (142).

In an early section, “Dream House as Time Travel,” Machado wonders whether knowing the relationship’s eventual course would have made a difference. Ultimately, she suggests the question is a moot point: history, like any story, is already down on the page. Trying to alter the past would be like trying to rewrite a novel as a character within it: “Time–-the plot of it––is fixed.” Instead, if there’s a kind of rescue mission in this text, it’s a different “you” than the past self it narrates: the “you” of a reader in need, the “you,” as Harmony’s post noted, of the dedication––”If you need this book, it is for you.”

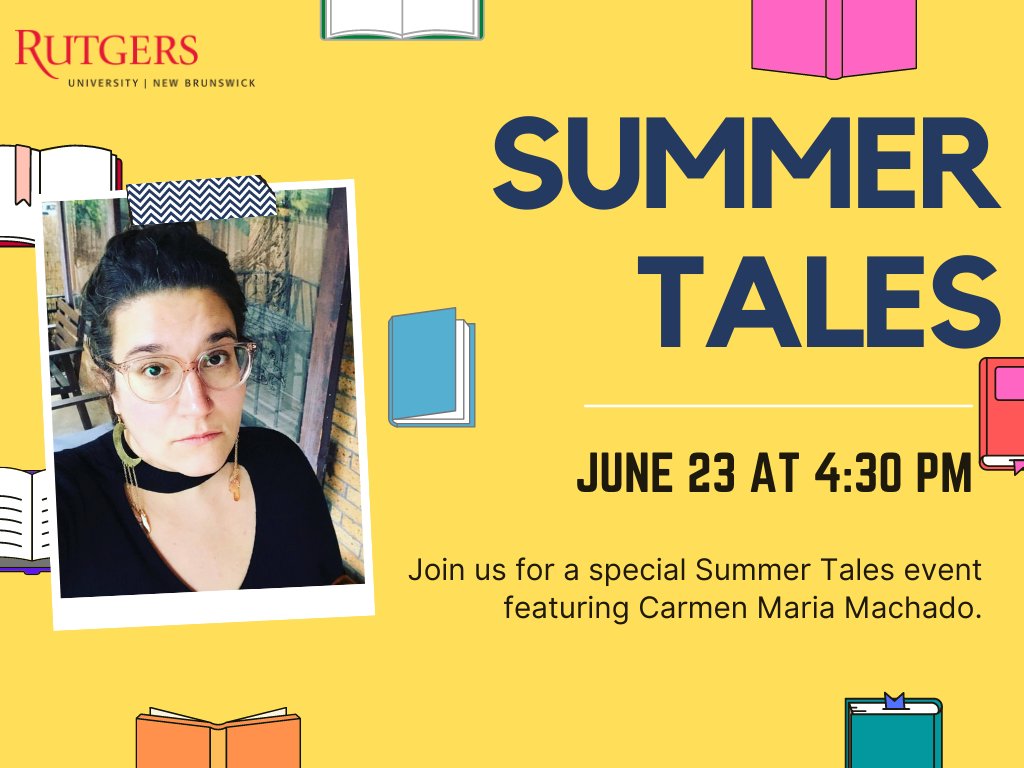

This is all to say that I found In the Dream House, like Machado’s story collection Her Body and Other Parties, fascinating as well as moving, and can’t wait to speak with her next week. (This post has also been a way of working through my own thoughts about it in advance so that I can ask better questions; I’m most interested in her thoughts about her work, not mine!) Do you have questions for Carmen Maria Machado? Let us know!