As a librarian, I personally find Banned Books Week extremely important, no matter where one lives. Since 1982, the week-long attention to challenging books for diverse reasons has been a great opportunity for American libraries to educate their users about intellectual freedom and raise awareness of emerging trends. Growing up with strict and extensive censorship in communist Hungary, I made it a priority in my current job to help readers understand the value of free and open access to information.

At our Banned Books Week read-out event in 2021, I talked about the Hungarian newsletter, which polled its readers to find out if professional organizations should raise their voices about banned books. With the new Hungarian law challenging librarians, it was only a matter of time before someone decided to just say yes to Banned Books Week outside the United States!

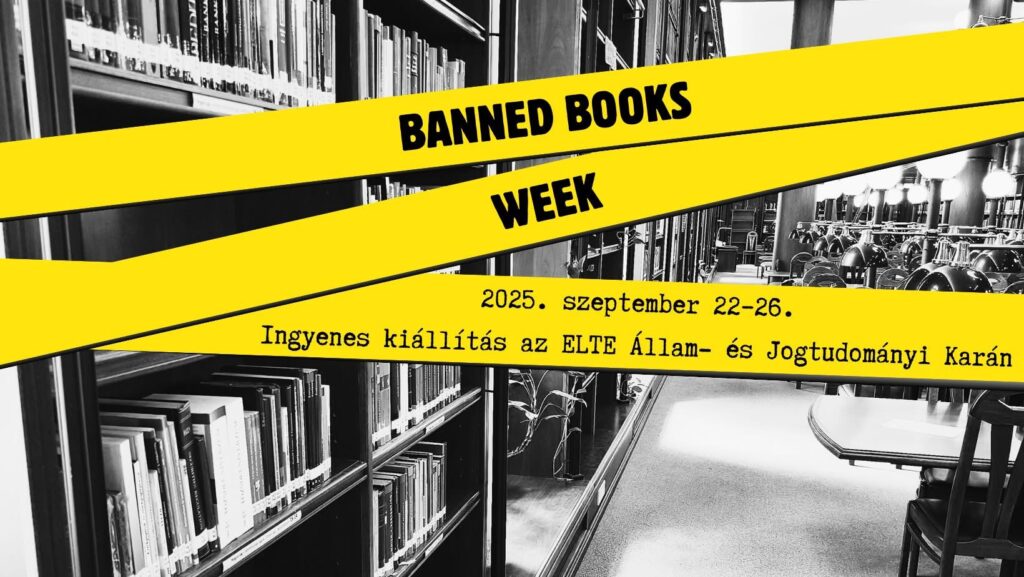

The first Hungarian Banned Books Week is held during the week of September 22-26, 2025, featuring a free exhibit and film screening at the Law School of the Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest.

Speaking with Books We Read (BWR) about the FIRST-EVER Hungarian Banned Books Week event (that we know of), are the two hosts:

- Dániel Takács, Head of Library, Faculty of Law, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary (DT)

- Gergely Gosztonyi, Professor, Faculty of Law, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary (GG)

BWR: In 2022, the two of you co-authored an eye-opening article, Könyvdarálás, könyvégetés, könyvbetiltás, about shredding, burning, and banning books posted on the Law-History blog hosted by ELTE Law School and Hungarian Academy of Sciences in Hungarian (translates fairly well into English by AI these days). In 2024, you followed up with a scholarly article entitled Gondolatszabadság vagy cenzúra Amerikában? (Freedom of thought or censorship in America) in Magyar Szemle [Hungarian Review], a thorough review of censorship in a historical context with plenty of literary examples close to Hungarian readers. This week, you are hosting the first Banned Books Week event in Budapest. How long have you been involved with censorship and banned books?

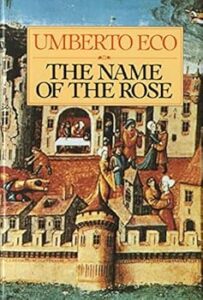

DT: The profession of librarians has always been concerned with the issue of accessibility, and thus, who can decide what readers have access to and how. One of my first experiences was Umberto Eco’s novel, The Name of the Rose, when I was still in high school. Since then, this question has been on my mind, sometimes more, sometimes less. My collaboration with Gergely Gosztonyi gave this initiative a definite direction.

DT: The profession of librarians has always been concerned with the issue of accessibility, and thus, who can decide what readers have access to and how. One of my first experiences was Umberto Eco’s novel, The Name of the Rose, when I was still in high school. Since then, this question has been on my mind, sometimes more, sometimes less. My collaboration with Gergely Gosztonyi gave this initiative a definite direction.

GG: Throughout my research career, I have focused on freedom of speech and its various restrictions. My career has always been marked by the duality of legal history and current legislation, so I have dealt with censorship both in a historical context and in today’s (including online) environment. My monograph, Censorship from Plato to Social Media: The Complexity of Social Media’s Content Regulation and Moderation Practices, published by Springer in 2023, also fits into this category.

BWR: I know you have been planning this for a while. What was the final push that gave you the idea of celebrating Banned Books Week in Hungary in 2025?

DT: There was no one particular turning point; we now have reached a consensus on a larger-scale project. In any case, it is thought-provoking that we are reading more and more news from around the world about censorship and book bans, and I believe it is necessary and worthwhile to respond to this.

GG: I can’t think of any one particular point that might have caused this, such as something that caused outrage. I completed a major research project in 2025, and I thought it would be a good way to conclude it if it could be turned into something tangible and educational for a wider audience.

BWR: You have a Banned Books Week exhibit set up at the Law Library. What were your selection criteria for displaying books and other artifacts at the exhibit? What are some unique items on display?

BWR: You have a Banned Books Week exhibit set up at the Law Library. What were your selection criteria for displaying books and other artifacts at the exhibit? What are some unique items on display?

DT: We would like to present the history of censorship in Hungary and the book bans that have been implemented throughout Hungarian history to the Hungarian public. In addition to works of fiction, this also includes 20th-century censorship affecting various academic disciplines, including legal literature, which we will also present to those interested.

GG: When we started planning this section, we had two basic ideas. First, it had to be relevant to Hungary, meaning that we wanted to present books that would be understandable to Hungarian readers (if we look at the ALA’s 2024 list, most of the books on it have not been translated into Hungarian). Second, it was important to us that it had to be understandable to a broad younger generation, too (which is why Harry Potter, for example, made it into the exhibit).

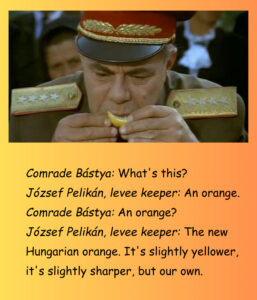

BWR: Your flagship event is related to a memorable movie, The Witness (Hungarian: A tanú), a 1969 Hungarian political satire film directed by Péter Bacsó. It is an incredible choice for a free public screening in 2025, less than a year from the Hungarian elections next spring. As I was explaining to my American colleague in the Archives the other day, the Hungarian language is full of tropes and quotes from this film, which was heavily censored and unavailable for almost a decade. I saw it in a highly controlled environment at the end of the 1970s, with “proper” contextual explanations spoon-fed to us, the “ideologically undereducated” masses. Now you have a screening and a discussion. What do you think students and viewers will take away from this event in 2025?

DT: Perhaps one of the most important and relevant messages of the film, which is still valid today, is the importance of reading between the lines. Hungary has a long tradition, dating back centuries, of hiding important messages, which can only be deciphered by readers and viewers who possess the appropriate decoding keys. This knowledge has faded among generations that have grown up since the regime change of 1989, but I believe it is important to revive it.

GG: The Witness is part of Hungary’s shared cultural heritage, one of those films from the 1960s and 1970s that remain relevant in basically any era. This is undoubtedly helped by the film’s language, the catchphrases that have been passed down from fathers to sons among Hungarians. But for me, what is more important is that it can help – even the law students I teach – to understand the parallels, similarities, and analogies between historical periods. No matter how cyclical mankind’s progress may be, it would at least have the chance not to repeat the Hungarian mistakes of the 20th century over and over again.

BWR: Oh, I almost forgot about reading between the lines (the incredibly useful social skill that my generation learned the hard way), because it’s second nature to me! To help new generations really understand freedom of speech, every little bit counts. As our colleague, former ALA President Nancy Kranich said: “Censorship succeeds when no one talks about it.” Can you tell us a bit more about some other activities you are planning? I saw some games and puzzles on social media, what else?

DT: This year, we are only preparing the exhibition and the related game, which will be complemented by a film screening and presentation on Researchers’ Night on September 26, and we will also place banned Hungarian poems in the library. If the event is successful, we would like to organize additional programs next year, such as a reading circle based on banned books, and we would also like to publish the results of our ongoing research.

BWR: Can’t wait to hear about them, including your research! I was delighted to find my 2021 article on banning books listed in the comprehensive bibliography of Hungarian-language literature on censorship (A magyar cenzúrairodalom bibliográfiája 1833-2025, edited by G. Gosztonyi and L. Kreiter) and published earlier this year. As I said, I find raising awareness about freedom of speech and access to information extremely important in a world where the three P’s (prohibiting, permitting, or promoting – my way of explaining the Hungarian three T’s) still prevail. What kind of impact can a scholarly publication like this have in the long run? Side note: I’m a huge fan of topical and comprehensive bibliographies.

DT: As librarians, bibliographies are essential to our work in providing information. I am confident that the bibliography we have created (and any future additions to it) will be useful in the life of the library, and we will use it every day to help our readers.

GG: I am also a big fan of bibliographies 🙂 They may seem a little old-fashioned, but at the same time, it seems that literature review as a genre is experiencing a renaissance, and bibliographies work on a somewhat similar principle. The Department of Hungarian State and Legal History at ELTE published numerous bibliographies in previous years, and the above-mentioned one fits into this series. My goal was, on the one hand, to provide a starting point for those who wish to deal with censorship in the future, and on the other hand, to pay tribute in some way to all those whose work I have been able to build on so much.

BWR: A related question, what do you think are the best ways to raise awareness about censorship and make an impact in Hungary today? How is it different from the United States?

GG: I don’t think there is any difference between countries in terms of how to raise awareness, as I feel that, nowadays, when it comes to censorship, the aim is not to draw attention to its existence (especially in relation to online platforms), because people are aware of that, but rather to make them understand the difference between content regulation and censorship, to make them understand the (different) limits of freedom of speech in the US and Europe, and to make them use the concept of censorship properly—not foolishly as most do in our tense and torn political culture.

BWR: Your Banned Books Week events are organized in a Law School as opposed to most American events, which are hosted by libraries. Do you think your students are more in tune with what’s going on in the world of book bans than the average student? Our library school students receive training on how to act when a user challenges a book. Is there anything similar you guide your students to do?

BWR: Your Banned Books Week events are organized in a Law School as opposed to most American events, which are hosted by libraries. Do you think your students are more in tune with what’s going on in the world of book bans than the average student? Our library school students receive training on how to act when a user challenges a book. Is there anything similar you guide your students to do?

DT: In Hungary, the process of banning books is much less transparent and tangible than in the US, so guidelines are not as easy to use as they are there. Unfortunately, in many cases, the financing of libraries (typically municipal or state-owned) and the fear of losing that financing make it impossible to purchase a questionable work—if the sought-after book can even appear on the market. As Gergely Gosztonyi pointed out above, today’s Hungarian books feature completely different content, which does not overlap much with American titles.

GG: Since this is the first event of its kind in Hungary, I cannot tell you about any such incidents. I consider these awareness campaigns important precisely so that young (and not so young) people are not caught off guard if they encounter such a situation. There is a very good quote by Ken Donelson (p. 51) that I always use as a guide:

“To fight the censor with any hope of success, we must prepare carefully before censorship strikes, not in the panic of battle. If we do not prepare in advance, or if we do not care enough to prepare, we will lose, and we will wind up losing everything, our books, our students, and our freedom. And we will be forced to tell lies to the young. Perhaps they won’t believe those lies, but the prospect that they might is a frightening possibility.”

BWR: These are great thoughts and can provide guidance anywhere. Now let’s talk about books actually banned in Hungary. I am old enough to remember reading classics such as Animal Farm and The Gulag Archipelago in their low-key (paper and binding), samizdat versions in the 1980s. I was wondering what personal experiences you had with book bans and censorship?

DT: Being a generation younger, I encountered censorship much more indirectly. On the one hand, through my reading (such as the aforementioned novel by Eco, but of course Orwell, Solzhenitsyn, Bradbury, Koestler, and Tatyana Tolstaya must also be mentioned), and on the other hand, through the discovery of how much of the literature we received as children and young people had been reworked before the 1990s — I am thinking here, among other things, of Karl May’s novels, from which all references to religion were completely removed.

DT: Being a generation younger, I encountered censorship much more indirectly. On the one hand, through my reading (such as the aforementioned novel by Eco, but of course Orwell, Solzhenitsyn, Bradbury, Koestler, and Tatyana Tolstaya must also be mentioned), and on the other hand, through the discovery of how much of the literature we received as children and young people had been reworked before the 1990s — I am thinking here, among other things, of Karl May’s novels, from which all references to religion were completely removed.

Thirdly, I must mention (also as a later discovery) how much Hungarian children and children’s literature owe to those authors who were silenced during the communist era and were forced to earn a living by writing children’s books—this resulted in a cultural heritage of fantastic quality and complexity. I also include here those authors who, circumventing official censorship from the outset, created texts not only for children, such as István Örkény, who perfected the genre of the grotesque short story.

GG: Due to my age, I did not read samizdat firsthand, but in my early teens, in the early 1990s, I visited the Gondolkodó Antikvárium second-hand bookstore many times, where I searched for all kinds of anarchist literature. Since even then my interests searched for out-of-the-system things, it was not difficult to come across Hungarian samizdat literature there. Besides that, in addition to punk, I was completely hooked on Hungarian alternative music of the 1980s. It is now clear to me how these interests led me, reinforcing each other, to examine freedom of speech and censorship as an adult.

BWR: At our read-out events, we all choose a book to read. My choice was The Case Worker, by G. Konrád. I read a few paragraphs in English and Hungarian. What is your favorite banned or challenged book? Or can you recommend one title that you think everyone should read?

DT: My favorite writings are those that recount World War II and subsequent Soviet captivity, or the Hungarian labor camp in Recsk, and which were completely banned during the communist era: János Rózsás’s (Solzhenitsyn’s friend) Keserű ifjúság (Bitter Youth) and Alfonz Nádasdy’s Hadifogolynapló (Prisoner of War Diary).

DT: My favorite writings are those that recount World War II and subsequent Soviet captivity, or the Hungarian labor camp in Recsk, and which were completely banned during the communist era: János Rózsás’s (Solzhenitsyn’s friend) Keserű ifjúság (Bitter Youth) and Alfonz Nádasdy’s Hadifogolynapló (Prisoner of War Diary).

GG: It’s not fair that I can’t choose The Case Worker as it is one of my favorite books 🙂 In this case, I would recommend The Velvet Prison: Artists Under State Socialism, by Miklós Haraszti, which shows the relationship between art, artists, and a totalitarian state. It is a fascinating book.

BWR: Thank you for your time! We are thrilled to share your event with the Rutgers community.

References

- Donelson, K. (1974). Censorship in the 1970’s. The English Journal, 63(2), 47–51. https://doi.org/10.2307/813680

- Gosztonyi, G. (2023). Censorship from Plato to Social Media: The Complexity of Social Media’s Content Regulation and Moderation Practices. Springer

- Gosztonyi, G., & Kreiter, L. (eds.) (2025). A magyar cenzúrairodalom bibliográfiája 1833–2025. ELTE ÁJK Magyar Állam- és Jogtörténeti Tanszék.

- Hajnal Ward, J. (2021). Tiltunk, tűrünk, támogatunk? – Betiltott könyvek hete az USA-ban [Prohibiting, permitting, or promoting? – Banned Books Week in the USA. In Hungarian]. Könyv, könyvtár, könyvtáros [Books, libraries, librarians], 30(9). 3-17.

- Takács, D., & Gosztonyi, G. (2024). Gondolatszabadság vagy cenzúra Amerikában? Magyar Szemle, 5-6, online July 1.