-Continued from Hungarian Refugee Scientists at Rutgers (Part 1)

-Continued from Hungarian Refugee Scientists at Rutgers (Part 1)

Language instruction

Students had a full schedule. In addition to classes 9 to 4 on weekdays, they had evening programs and all kinds of special events, all added to their job search. The eight-week course started on Monday, January 21 with twenty-nine students, including scientists as principals, while spouses were also allowed to participate. Two children were enrolled in the local elementary school. At first there was only one instructor from the Department of Romance Languages, the only one who was available to take the assignment on such short notice with experience teaching ”English for the foreign-born,” as they called it at that time.

Another instructor from the same department joined the team two days later, so it was possible to divide the group into total beginners and a so-called “intermediate” group, which included those who had some previous English instruction and knowledge. However, when seven more students arrived at the end of the week, there seemed to be a dire need for further division and one more instructor. Recruiting another member of the department allowed for splitting the elementary class. At the peak of the program, the two elementary groups had thirteen members each, and there were fifteen persons in the intermediate group. The daily schedule was more or less identical throughout the whole course.

They used one of the popular adult ESL textbooks. With its structured grammar and traditional lesson plans, the methodology seemed familiar to anyone who learned a second language in Hungary. The lessons covered everyday situations with useful vocabulary, even some idioms. The general emphasis was on developing strong speaking skills with good pronunciation and simple but solid grammar. With a basic vocabulary of about 1000 words, topics included American customs and family life. Each lesson introduced an average of 40 to 50 new lexical items in useful conversational context, which also served to illustrate basic grammatical principles.

They used one of the popular adult ESL textbooks. With its structured grammar and traditional lesson plans, the methodology seemed familiar to anyone who learned a second language in Hungary. The lessons covered everyday situations with useful vocabulary, even some idioms. The general emphasis was on developing strong speaking skills with good pronunciation and simple but solid grammar. With a basic vocabulary of about 1000 words, topics included American customs and family life. Each lesson introduced an average of 40 to 50 new lexical items in useful conversational context, which also served to illustrate basic grammatical principles.

The day started with pronunciation drills and recording speeches. Each student read a short paragraph, which was recorded and played back for evaluation. Intensive and repeated practice with the tape was meant to reinforce correct pronunciation and intonation. Oral reports on homework assignments and short compositions were also part of the daily language learning methods. Problems reported are the ones still common to Hungarians learning English (the pronunciation of th and w, remember Bela Lugosi saying BEVARE?).

Conversation hours were organized daily with American students, with the aim of having a one to three American-Hungarian ratio. Students from Rutgers and Douglass Colleges (i.e., men’s and women’s colleges at that time) were recruited for this language learning activity. The scientists showed great interest in this method of learning. From the third week on, the Interfraternity Council agreed to recommend to the fraternities that a particular house should be responsible for each day of the week and should provide five men to converse with the scientists from 4 p.m. to 5 p.m. Sometimes more men showed up than expected, and the number of Douglass female students also remained consistently high, providing a wonderful opportunity for practice.

To measure progress, at the end of the course everyone took the language proficiency test “English Examination for Foreign Students,” compiled by the Institute of Psychological Research at Columbia University. The intermediate group had also taken the exam on January 28, allowing to compare results. The multiple choice test was divided into four sections, testing basic grammatical patterns, correct sentence structure, vocabulary , and reading comprehension. Those who took the test twice showed significant improvement during the six weeks.

To measure progress, at the end of the course everyone took the language proficiency test “English Examination for Foreign Students,” compiled by the Institute of Psychological Research at Columbia University. The intermediate group had also taken the exam on January 28, allowing to compare results. The multiple choice test was divided into four sections, testing basic grammatical patterns, correct sentence structure, vocabulary , and reading comprehension. Those who took the test twice showed significant improvement during the six weeks.

Extracurricular activities

The course also presented a great opportunity to introduce the Hungarian refugee scientists to American culture in the form of evening lectures and discussions. These were conducted by top scholars of the field from Rutgers, Yale, and other universities in the vicinity. The topics included general conversational themes, such as American customs, manners, civilization, race, religion, the political system, the economy. Presentations were also offered on many scholarly, scientific, and academic topics, including American geography, art, architecture, music, and even concerts. The timing of the topics also considered the language proficiency of the audience, starting with the ones requiring less language and more familiar content such as music and arts.

This secondary purpose of the program raised questions from the beginning with the main issue being time constraints. At first, it was not clear whether group members would be too overwhelmed with language classes, homework assignments, job search and placement interviews, which also required some travel. The next issue was the English proficiency of the participants and the lack of Hungarian-speaking lecturers. Of sixteen programs, only one was given in Hungarian, a talk on American customs and manners by an Academy staff member, Dr. Ferencz. This lecture was probably effective for another reason too: she was able to talk about American issues as seen through the eyes of a person born in Hungary.

Translation was needed for the rest of the presentations, which inadvertently broke the natural flow of discussions and made communication extremely difficult. Given their background, another major concern was whether the refugees would interpret these lectures as indoctrination and American propaganda.

Other than the daytime language and evening orientation programs, there were events scheduled to offer diversion from studying. Most Sunday nights, the entire group gathered in the Rev. Abernethy’s home, with faculty, friends and family members also invited. These programs were entirely informal, they were just listening to classical music, singing, and talking, often sitting on the floor. On Saturdays, there was an optional basketball game scheduled in the gym. As with other weekend special events, the scientists had a chance to visit several departments, institutes and the library at Rutgers.

The first week included a trip to New York City to get new clothes and see a show at Radio City on Tuesday. On one Saturday morning, Edward Teller, the Hungarian born father of the hydrogen bomb, member of the Manhattan project, met with the group in the dorm lobby. In the afternoon, the group went to Princeton, where Eugene Wigner showed them around in the Physics building, introducing them to other Hungarian born professors. In addition to the visit by Teller, the group was also visited by General Béla Király in March. Both events are marked in the official records as incorporating off-the-record talks.

Little documentation has been found on these discussions, but from the Rev. Abernethy’s report it is clear that Edward Teller gave a lot of advice to the incoming scientists. He pointed out the unusual opportunities for scientists in America, but also indicated the challenges everyone must face in a new country. He stressed the point that they should not settle in a Hungarian community, but rather try to establish the closest possible connections with American life and American people.

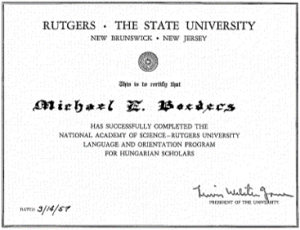

Following the language proficiency exam on March 12, the program was completed with a formal session of “graduation exercises” on Thursday afternoon, March 14 in the auditorium of the Institute of Microbiology. This event followed the formal traditions of the university graduation. Officers and representatives of the Academy, the President’s Committee, and Camp Kilmer also attended the event. After an invocation and comments on the significance of the program to the university, the nation, and the world of science by Rutgers President Jones, Dr. Voorhees, and Dr. Bonk, three refugee-students responded in English. Then the members of the graduating class proceeded to receive their certificates of successful completion of the course. The ceremony was followed by a reception in the home of President Jones.

Career path of the refugee scientists in the United States

Who were these people? Among the participants in the Rutgers course, the following professions are listed: organic chemist, chemical engineer, chemical engineering student, analytical chemist, plant pathologist, wine tester, geology and geography teacher, architect, aircraft engineering student, and psychologist.

Most of the refugee scientists kept in touch with the Rev. Abernethy. He also made significant efforts to collect and document the changes of address and jobs of the Hungarian scientists. Other than maintaining regular correspondence with some scientists, he would periodically check on them by mailing a little postcard requesting updates. These letters and cards yield an impressive list of employers who hired graduates of the program.

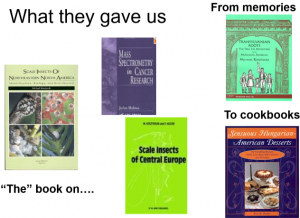

Their successful Integration in US Science can be illustrated by seminal publications in their fields, while they also collaborate with Hungarian scholars as co-authors or hosts.

Their successful Integration in US Science can be illustrated by seminal publications in their fields, while they also collaborate with Hungarian scholars as co-authors or hosts.

Recognition

The new language and culture are considered major barriers in a new country. Even with addressing these issues consciously and continuously, acculturation might be a long, painful process. Along the road toward integration into the new culture, structured language instruction coupled with early efforts to develop cross-cultural competencies seem to work for many.

In a short period, a successful language and cultural orientation program was designed and implemented, made possible by external funding, the flexibility of Rutgers, and many volunteer hours. The organizers focused on the main objective of their target audience, and customized the program along the way.

From the evening lectures and discussions, the ones conducted in Hungarian were most often mentioned as beneficial, also due to the nature of the topics of very practical value, such as salary, job security, comparison of jobs in the industry and academia. Everyone agreed that the atmosphere was very friendly and they found the program useful.

One of the instructors, speaking of the remarkable progress of the scientists in their English studies, pointed out their ability and willingness to learn English. He also said “I think their adjustment has been due primarily to the fact that they have been treated as intelligent adults and have never felt that they were the objects of propaganda.”

Source: Rutgers University Libraries Special,Collections, Tracy D. Vorhees Papers

*Based on the author’s presentation: The Rutgers English Program for Hungarian Refugee Scientists in 1956. Invited talk at the Rutgers 250th Anniversary event: The Cold War at Camp Kilmer: Hungarian ‘56ers, Cubans, and US Refugee Policy in New Jersey. March 2, 2016.

Research conducted at the Information Services, Center of Alcohol Studies (2007-2016). Co-investigators: Sylvia D. Clark (St. John’s University), Frank Jolliffe (Bank Street College), Molly Stewart (Center of Alcohol Studies Library, Franklin Township Public Library).

Images: Rutgers Special Collections and University Archives