Interviews with Authors: A Bibliotherapy Reader in Hungarian

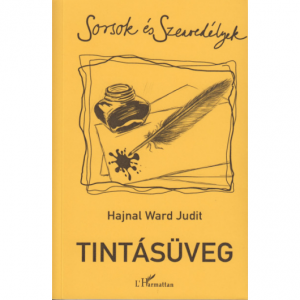

Judit Hajnal Ward often publishes in her native Hungarian in topics related to Library and Information Science. Her book entitled Nyitott Könyvtár (Open Libraries) was published in 2015 by Kalligram in Budapest. The second interview in the series focuses on her latest book, related to bibliotherapy in libraries, pictured here: Tintásüveg (English: Ink well), published in 2019 by l’Harmattan.

NA: At the Banned Books Week event in September you were talking about Hungarian books being challenged due to a new law. My understanding is that this law applies to all books dealing with LGBTQIA topics and addressed to audiences under 18. With that in mind, I wanted to ask you about your recent Hungarian-language bibliotherapy reader entitled Tintásüveg (English: Ink well), published in 2019 by l’Harmattan. This book touches on LGBTQIA topics––has it been affected by the new regulations, and do you think it will weather the storm?

JHW: First, thank you for the opportunity to talk about the book––well, not just the book, but more its reception in the light of my original intentions in writing it. It’s always easy to grab attention via a controversial topic, inadvertently or intentionally, but that was not on my agenda at all. It just happened that the Háttér Society, the largest and oldest currently operating LGBTQI organization in Hungary, featured it on one of their “Library Tuesdays” on Facebook, and then the librarian was pictured with my book on top of a pile of other new acquisitions in an interview. I couldn’t help looking up the bibliographic record for the book under the new law, which labels the book as containing “moderate LGBTQI content.” Looking back to the book, which consists of 12+1 short stories and two essays related to bibliotherapy (i.e., how to use these stories for guided therapeutic reading) I realized that more than half of them do touch upon LGBTQI topics. It was not intentional, but simply a part of our everyday life on this side of the pond. What’s going to happen with similar titles? I don’t know. This is probably not a book that will make it to multiple editions.

JHW: First, thank you for the opportunity to talk about the book––well, not just the book, but more its reception in the light of my original intentions in writing it. It’s always easy to grab attention via a controversial topic, inadvertently or intentionally, but that was not on my agenda at all. It just happened that the Háttér Society, the largest and oldest currently operating LGBTQI organization in Hungary, featured it on one of their “Library Tuesdays” on Facebook, and then the librarian was pictured with my book on top of a pile of other new acquisitions in an interview. I couldn’t help looking up the bibliographic record for the book under the new law, which labels the book as containing “moderate LGBTQI content.” Looking back to the book, which consists of 12+1 short stories and two essays related to bibliotherapy (i.e., how to use these stories for guided therapeutic reading) I realized that more than half of them do touch upon LGBTQI topics. It was not intentional, but simply a part of our everyday life on this side of the pond. What’s going to happen with similar titles? I don’t know. This is probably not a book that will make it to multiple editions.

NA: The title Ink well is a play on words in English––both a physical object (the ink in which you dip an old-fashioned fountain pen) and a sort of invocation to write skillfully and creatively (“ink well”). I know it’s a translation from the Hungarian but I wondered what kind of wordplay or double meaning might exist there. What exactly did you have in mind when you chose this title?

JHW: “Ink” definitely refers to writing and creativity in Hungarian, too. But the word “tinta” is slang for alcohol in Hungarian. The word “tintásüveg,” i.e., the bottle, ink well refers to a poem by 19th century Hungarian poet, Sándor Petőfi, albeit not a representative example of his work at all. It’s about a poor travelling actor, who was given a temp job out of the blue to copy a theater program brochure. After making a few bucks, on his way home he purchased ink for the next potential gig. Happy as he was, he was jumping around wildly with the ink well in his pocket. He ignored the warning from his friends not to do so or else “your spirit will be taken over by grief.“ The ink spilled, leaving a nasty blue stain on his yellow coat. Disappointed by the stain on his only coat, he ended up wearing it till the coat fell apart. This is the story, written in playful format, which complements the message––if there is one, as we often add in bibliotherapy. With so many interpretations, the poem is an excellent candidate for a bibliotherapy session. So are the stories in the book.

NA: The book is an addiction bibliotherapy reader that evolved during the last two years of the existence of the Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies Library in 2015-2016. As I recall, at that time we were working on Reading for Recovery (R4R), a project funded by a Carnegie-Whitney grant from the American Library Association to develop bibliotherapy resources for recovery from substance abuse problems. In this collection you’ve taken that spirit in a new direction: not just reading and cataloguing stories for bibliotherapeutic purposes, but writing your own. What exactly is bibliotherapy, in your definition? How is the term different as interpreted in Hungary, or elsewhere around the world?

JHW: I am glad you brought up R4R. There are so many interpretations of bibliotherapy, but for our purposes in R4R we defined it as using books from a list created under the guidance of a subject expert in order to address a therapeutic need, in our case, substance use issues. Librarians also act as “accidental bibliotherapists,” borrowing Liz Brewster’s phrase. The book followed this definition, bearing in mind that the very first structured use of books for therapeutic reasons related to alcoholism happened in Hungary in the 1980s. I had the opportunity to meet with the insightful and forward-looking librarian behind that program, Éva Bartos, in person at a conference panel on bibliotherapy, alongside Judit Béres, a pioneer in training bibliotherapists in an academic setting at the University of Pécs, Hungary. The clear distinction between clinical and developmental bibliotherapy inspired me to advance with the project in libraries, as, unlike in Hungary, in the United States librarians do not have an academic path, such as a master’s program, to become licensed or accredited bibliotherapists. To conclude with the name-dropping, I was delighted to accept an invitation from Zsolt Demetrovics to revive their series “Lives & addictions” of traditional addiction stories, sponsored by the School of Education and Psychology at Eötvös Loránd University.

NA: Sounds like your book benefited from R4R. How did the experience of creating a bibliotherapy resource for American audiences end up into a Hungarian book? Do you think your stories will be meaningful for the target audience?

JHW: It benefited tremendously, the stories wouldn’t have morphed into a book without R4R and you guys. My goal was to write short stories related to substance use along with prompts to inspire a dialog and reflect on the self. Based on the best Hungarian bibliotherapy practices, I believe that the American setting with global reach would somewhat alienate and separate readers abroad from their own personal situations, allowing more self-evaluation. The idea of talking points and discussion questions has roots in R4R, where we provided some, but also encouraged moderators and readers to come up with their own. A well-formulated question not only makes you think, but is oftentimes half of the solution, as common wisdom goes. The universal topic of insomnia we often explored reading F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Sleeping and waking inspired my story, Aurora, a similar experience related by an aging woman reflecting on her life in a sleepless night. This story is used in the book to introduce our methodology, and how to get the most out of these stories. I was delighted to hear that not only are these stories now used in therapist training, but in other courses too. One instructor shared a couple of essays written by college students in a social worker program using the stories, and I was delighted to see that the characters do speak to Hungarian audiences (even the one about the runner)!

NA: Although I was unable to read your book since it was published in Hungarian, I’ve been around its entire process of composition while we were working on bibliotherapy-related research, projects, and events at Rutgers since 2014. We talked extensively about these stories, the various situations and how to best describe them. The characters in the book and many of the plot twists you shared show some resemblance to some of the happenings around us. How do you create your characters? Are they based on real life examples or are they figments of your imagination?

JHW: By default, no. A disclaimer was added to that effect. But, accidents happen. Small details are always picked up by authors and make it into the book. You know, Nicholas in a white shirt and tie walking to teach his first class in college compared to Nick wearing jeans and t-shirt in the library. I believe it boils down to the normal way of writing or any creative activity: observe, digest, shape your sentence to express.

NA: Speaking of the guy in the library, who is your favorite character in the book? Is it the long-distance runner?

JHW: Well, the female pacer with her food allergies and a cute dog is definitely close to me, you got that right. However, if I have to pick a favorite, it would be Transmama, the mother who struggles with her transgender kid. The story is pretty simple, a woman inching in traffic on Interstate 287 due to a fatal motorcycle accident. She is on her way to work, where she will have to request unscheduled time off to accompany her child to a gender confirmation surgery. You can predict the uncertainties swirling in her head, complemented with messing up the gender-appropriate language. In the end, a mother’s unconditional love prevails. It’s a work in progress for every parent, regardless of issue at hand: do whatever is the best for your child even if it hurts or you feel clueless.

NA: The other day we were talking about the narrator’s perspective in various texts. How do you choose the point of view in these stories?

JHW: Well, I can only confirm what we suspected in that conversation. Consciously or not, I tend to use the first person singular, i.e., the popular angle in autobiographies, in stories that do not hit too close to me. This may not make sense and may not sound intuitive, however, the character telling the story serves perfectly to express their personal emotions with a sense of intimacy. Interestingly, first person doesn’t work with other stories. I can only try to choose to be the omniscient narrator with insights into all my characters’ feelings and thoughts, or even one of them. I think it can be explained with the experience that writing a first person narrative in an addiction-related story is so intense that it would take me to some really dark places. I believe it’s a way of self-help and self-protection to keep the distance and write in third person, which is often a third person limited point of view, with insight into one character’s thought processes.

NA: How is this book different from other similar books written in Hungarian?

JHW: Coming from the addiction field, with its strong and distinctive storytelling traditions, has definitely contributed to setting this book apart from others. If you consider the AA “Big book,” AA Grapevine, even just an AA meeting, it’s classic storytelling. The Hungarian field focuses on literature therapy, so mostly poems and short stories of renowned authors. My stories bring up pretty common, everyday stuff. The story matters, the language matters. I must admit that I received tremendous assistance and encouragement from two experienced Hungarian editors and friends.

JHW: Coming from the addiction field, with its strong and distinctive storytelling traditions, has definitely contributed to setting this book apart from others. If you consider the AA “Big book,” AA Grapevine, even just an AA meeting, it’s classic storytelling. The Hungarian field focuses on literature therapy, so mostly poems and short stories of renowned authors. My stories bring up pretty common, everyday stuff. The story matters, the language matters. I must admit that I received tremendous assistance and encouragement from two experienced Hungarian editors and friends.

NA: What can you tell us about the two introductory essays to the book?

JHW: Intended to be integrated parts, they render the book also as a scholarly resource, used in bibliotherapy education, along with the stories and discussion question. Judit Béres, known for founding current bibliotherapist training in Hungary, reviews the field, provides context to these essays as well as guidance on using texts for bibliotherapy in addiction and beyond. I believe I have quoted her wisdom before. “A text appropriate and effective for therapeutic purposes has the potential to evoke (positive or negative) feelings and experiences of the reader, to lead them to important understandings, and to become a catalyst for conversations and creative writing” (In Hajnal Ward, Judit: Tintásüveg, p. 16, translation by J.H. Ward).

In my essay, I simply shared how R4R evolved into this book, highlighting creative ways to cope, also known as creative bibliotherapy on top of receptive bibliotherapy. Basically, read the story, see how it speaks to you, then write your own. Or sketch, or graphic design, anything that occupies the mind creatively.

NA: Why are you writing in Hungarian? Do you think there will be an English version of the stories?

JHW: I believe the first path for making sense of the world around you, even for the multilingual brain, gets laid down in your first language. I envision my peers, I try to explain something from my world to my 87-year-old dad or my disabled cousin, who hadn’t left the house for years, that will put my miseries and mysteries into perspective. This process helps me understand the world around. Then there’s the sense of purpose that I get from being involved in things only I can do, such as bridging these distinct cultures in a library and literary context. Look at our banned books week content: l can speak not only from a different perspective than other American librarians, but also freely when my peers back in Hungary can’t. I do write in English too, when I have something to say to that audience.

NA: What are you working on now?

JHW: I am finishing up Crossroads*, volume 2 of the reader, with a similar structure. It’s difficult to find time to write, but I enjoy collecting ideas and crafting sentences to use for a next story, I can get totally absorbed in the writing process. Being a librarian definitely helps, as I am exposed to diverse users and texts that I’d probably miss on my own. Like a car accident, you never know when inspiration will hit you. I believe we can also share that you and I have a book under contract related to this topic with ALA Editions. The working title is Shelf Help: A Handbook for the Accidental Bibliotherapist.**

*Published in 2023 by l’Harmattan

*Published in 2023 by l’Harmattan

**The final title of the book is The Librarian’s Guide to Bibliotherapy, available from the ALA Store.

Art librarian Megan Lotts recently published a new book entitled Advancing a Culture of Creativity in Libraries: Programming and Engagement. It gave us the idea to launch a new interview series about titles that Books We Read affiliates have written or are currently working on.